VII. Unexpected Galactic Redshifts

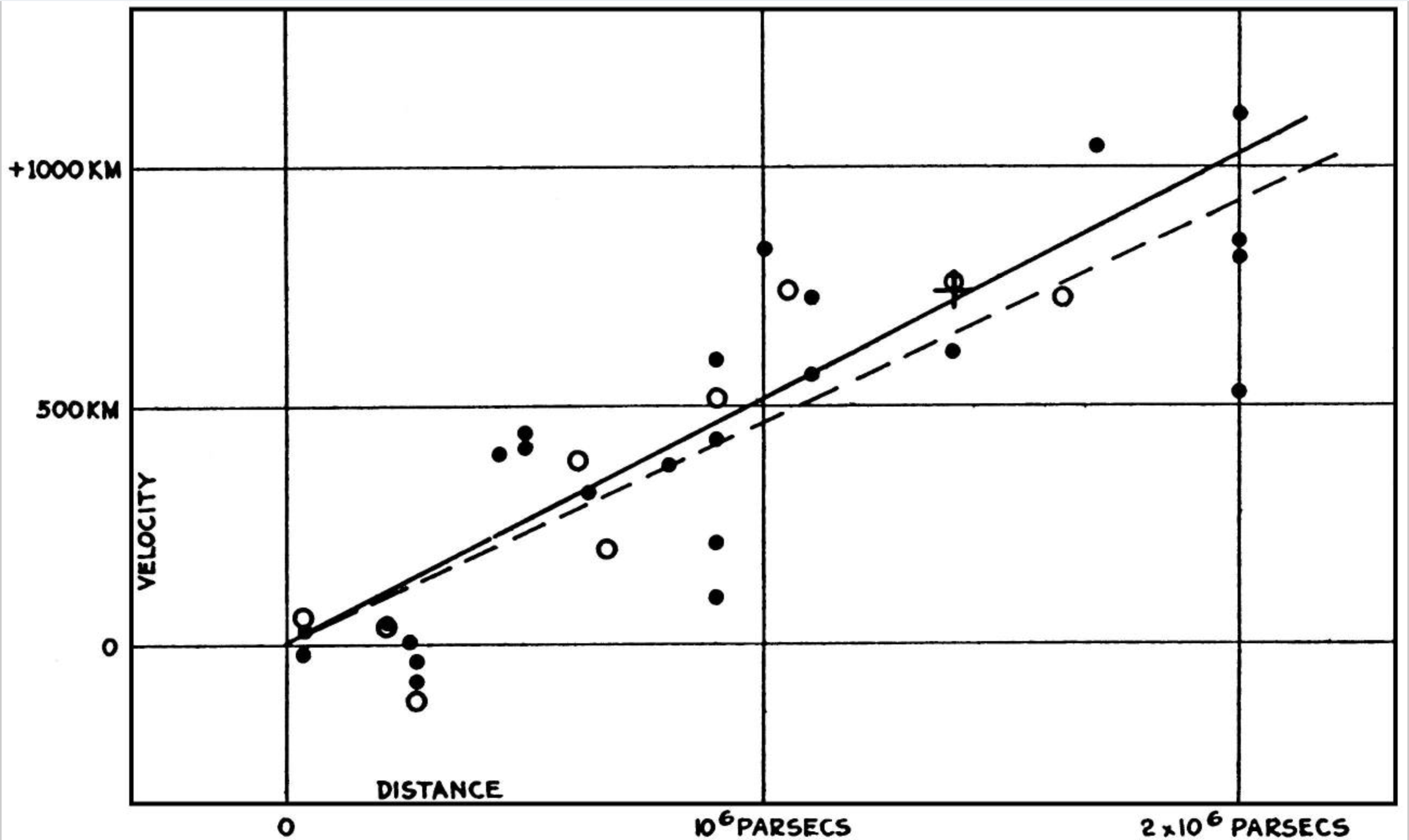

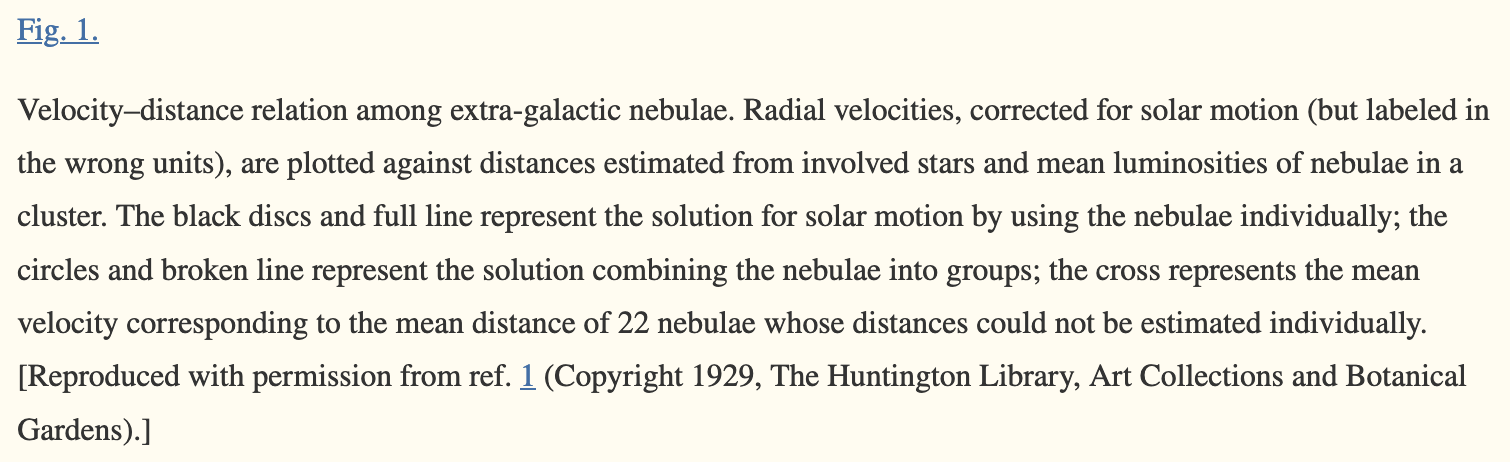

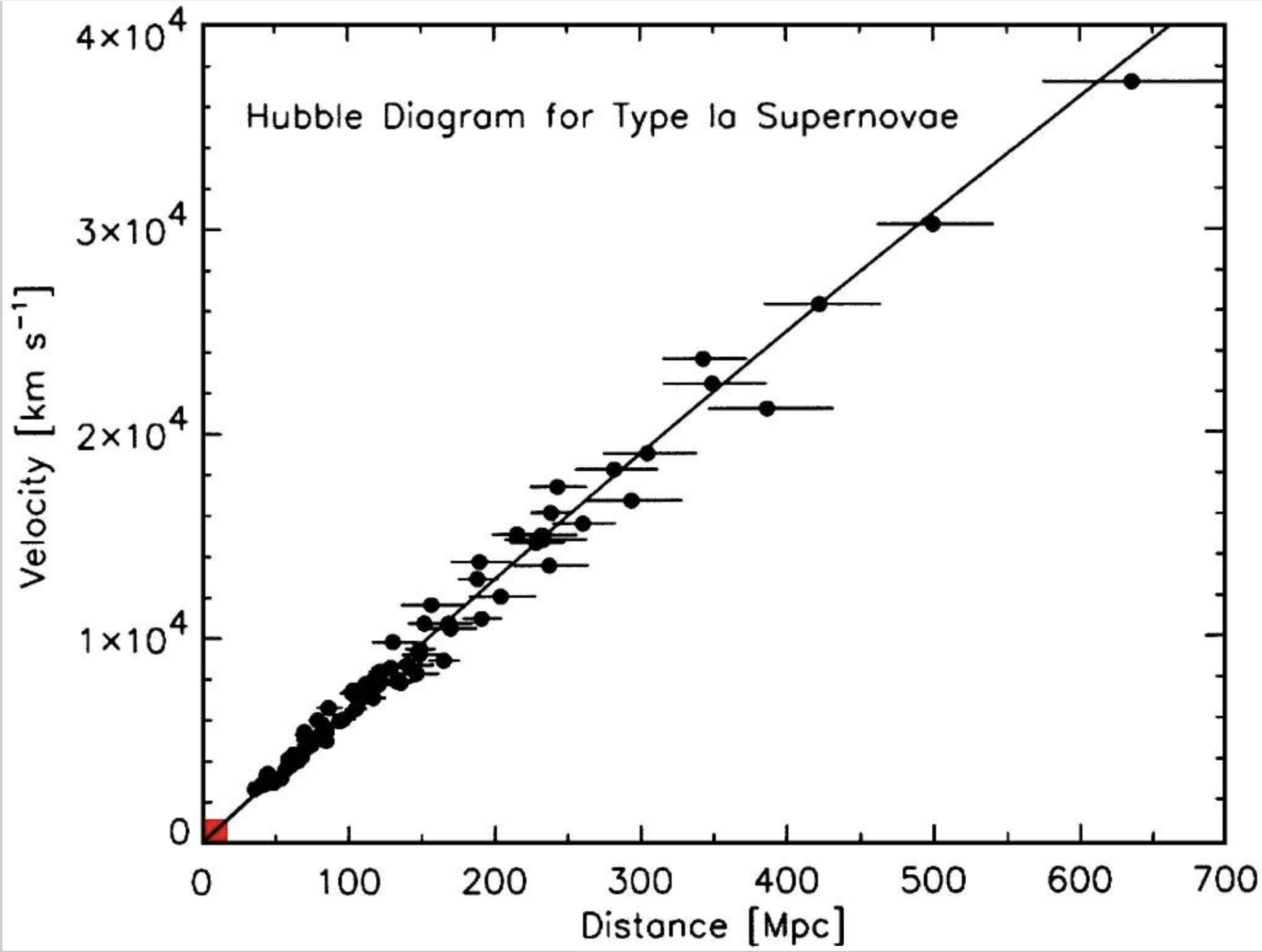

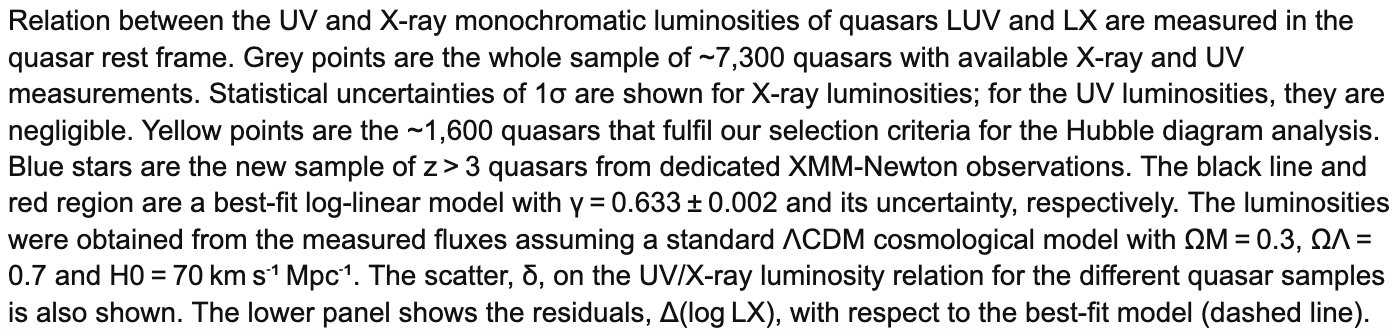

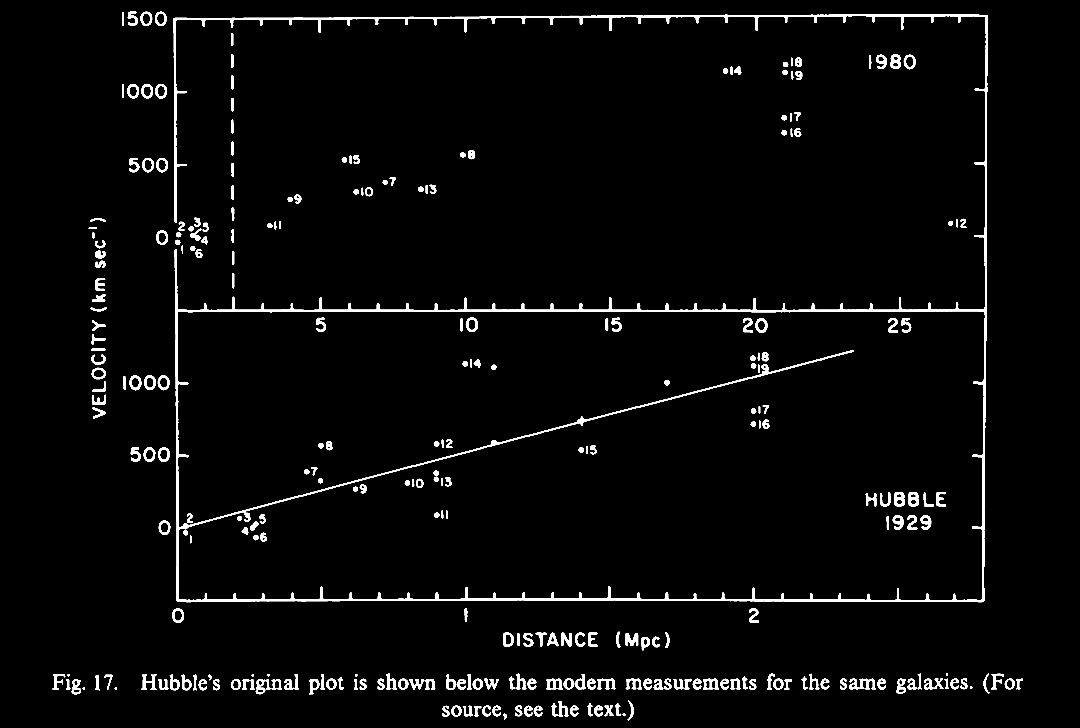

Expected Hubble distance-velocity relation

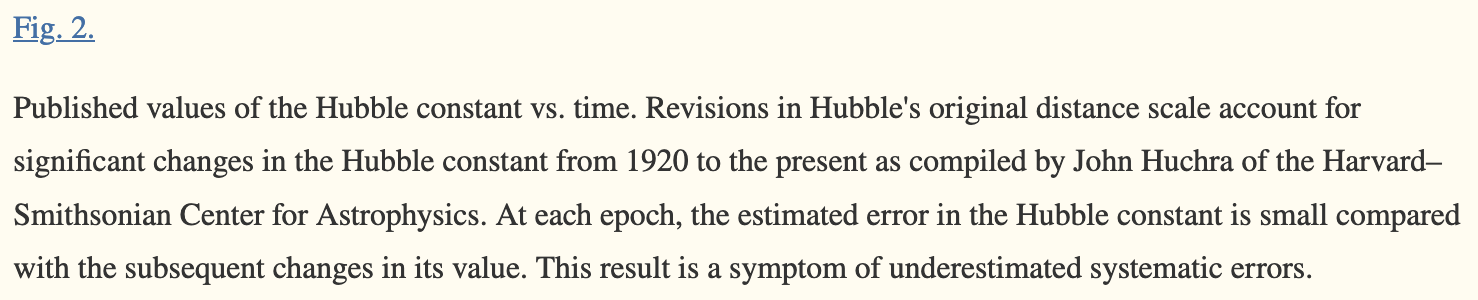

1930: H0 = 558

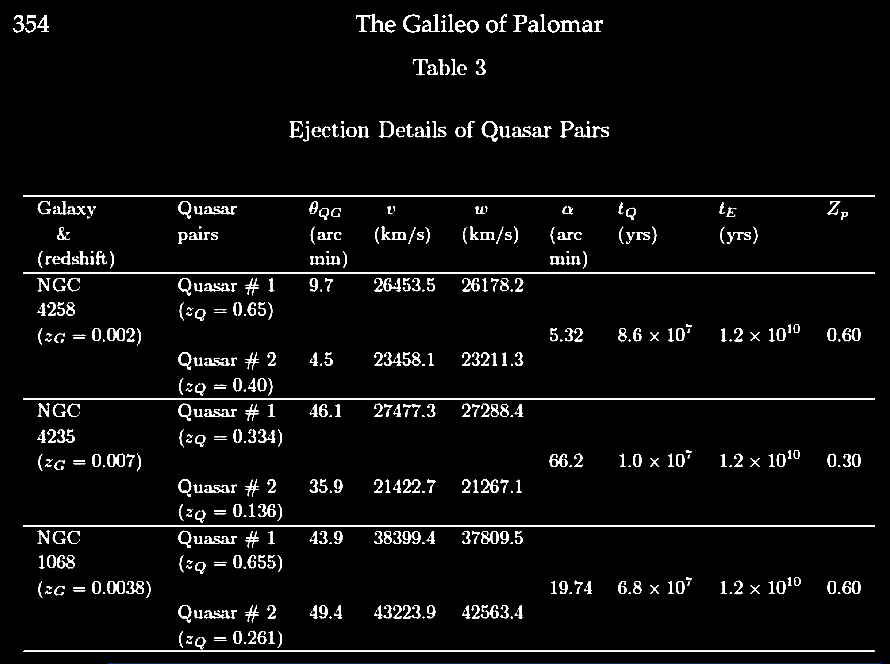

km s−1

Mpc−1

Intervening years: H0

= 30-100 km s−1

Mpc−1

Today, although narrowed,

we still have a range of values: H0 =

~63-75 km s−1

Mpc−1

|

|

|

|

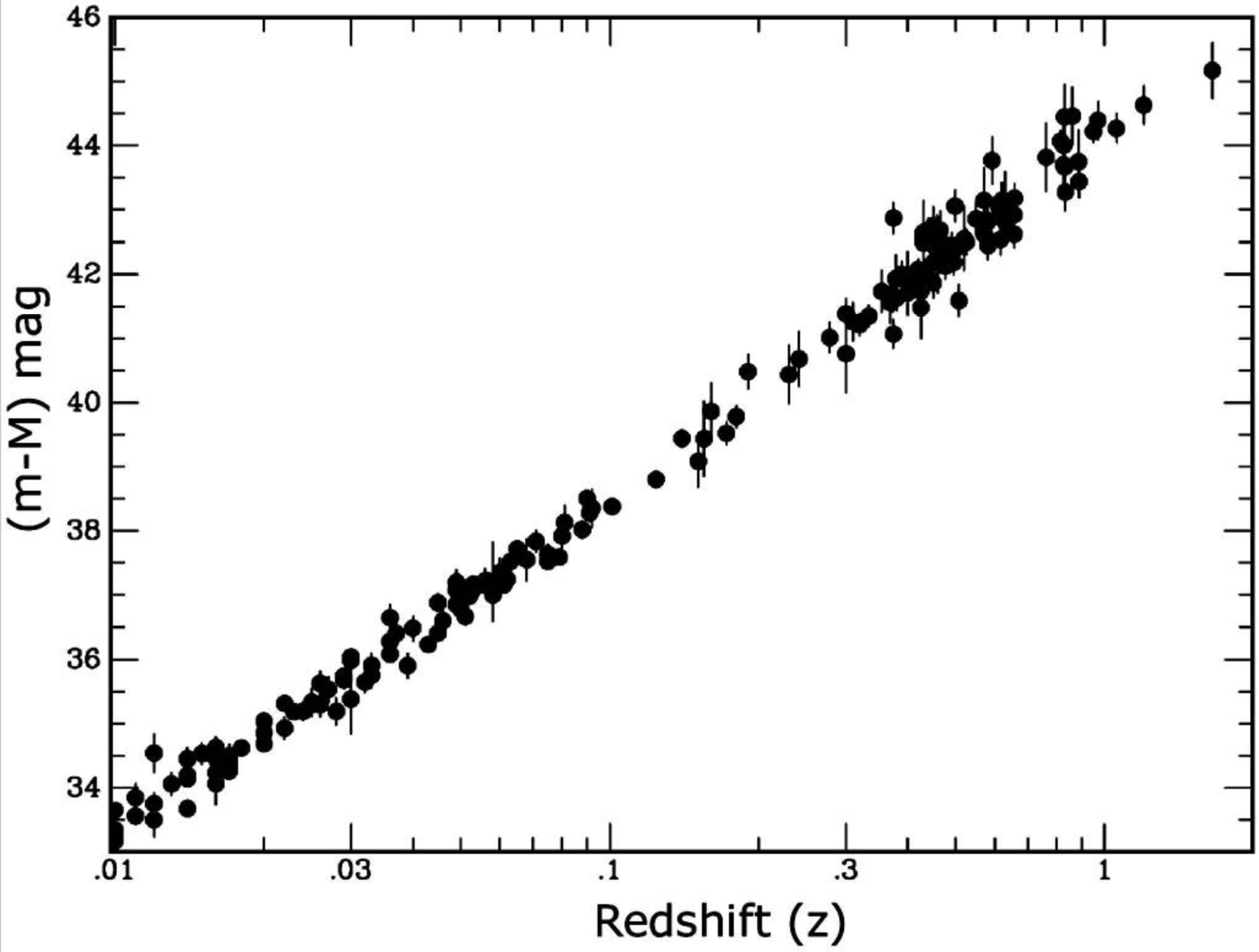

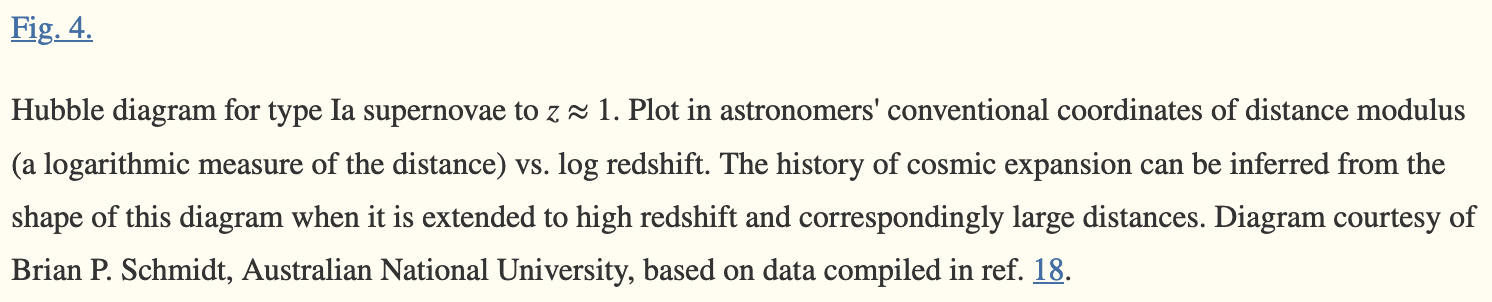

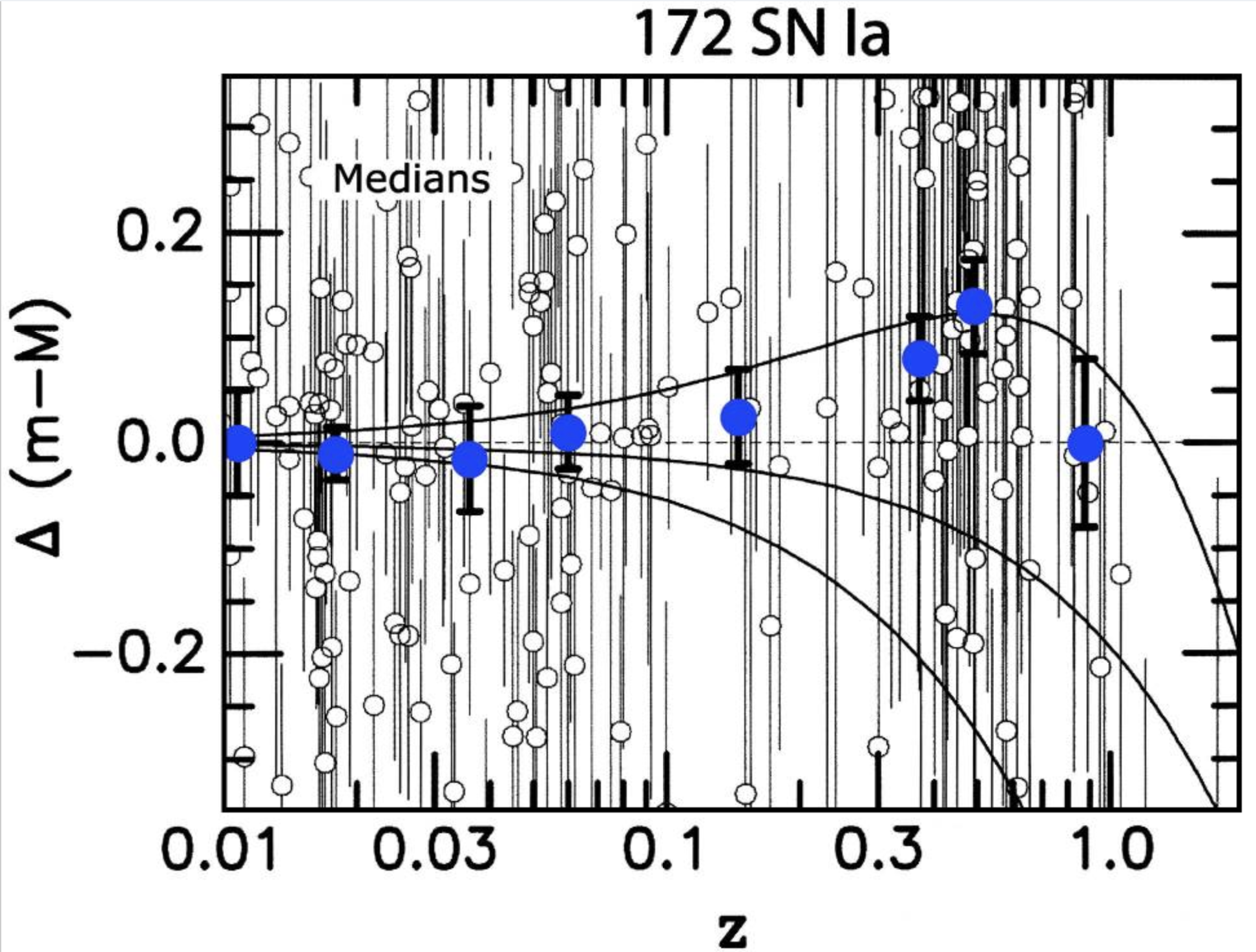

Above, we see

the 2004 estimates of the SN1a acceleration data compared

with various HBBC models with chosen proportions of 'dark

energy' and 'dark matter' (Kirshner, 2004; link).

Their review was in many ways far too simplistic to fully

consider the magnitude and complications of the ad hoc

free-parameter fitting required in HBBC models.

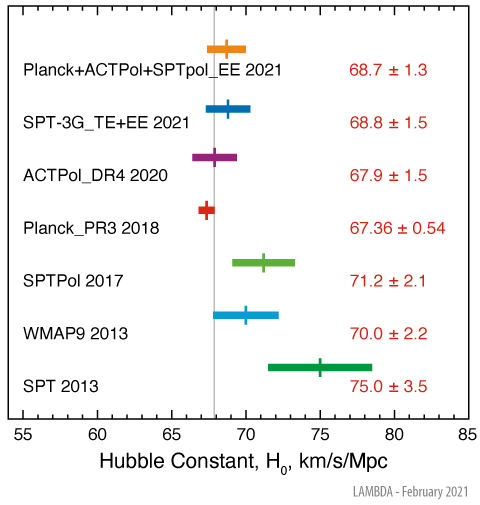

In the NASA

website of the Lambda working group, they attempted to

provide a summary of the many estimated values of the Hubble

constant H0

from a series of major studies done from 2001 to 2021. This

serves to highlight the difficulties of nailing down this

supposed constant:

Hubble Constant (NASA / LAMBDA Archive Team; link)

PNG

(480 x 697 px) 38Kb PNG

(1024 x 1488 px) 39kb PNG

(2048 x 2975 px) 194kb

PDF

77kb (Vector Art) SVG

57kb (Vector Art) EPS

41kb (Vector Art).(https://lambda.gsfc.nasa.gov/education/graphic_history/hubb_const.cfm).

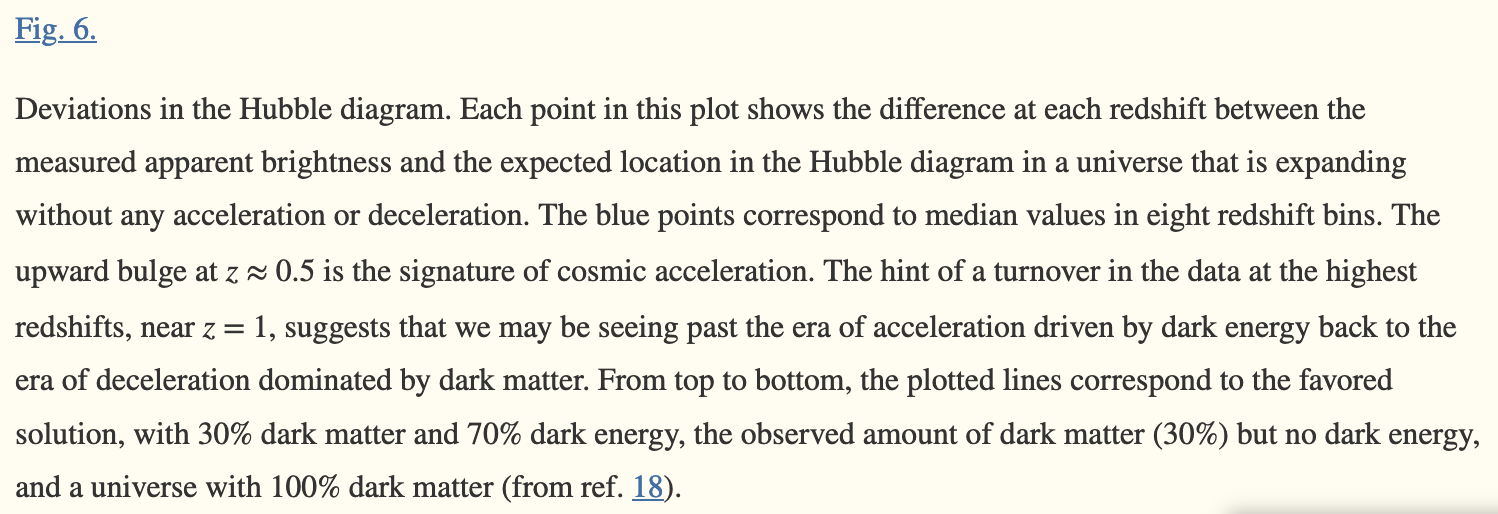

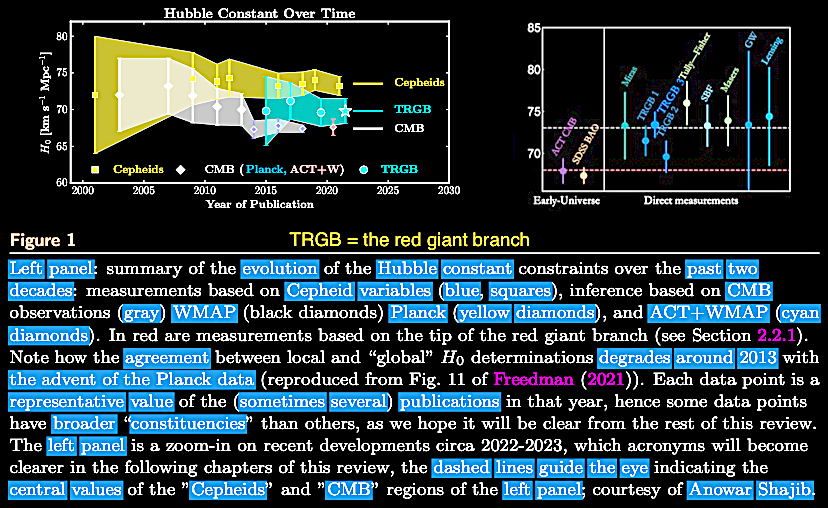

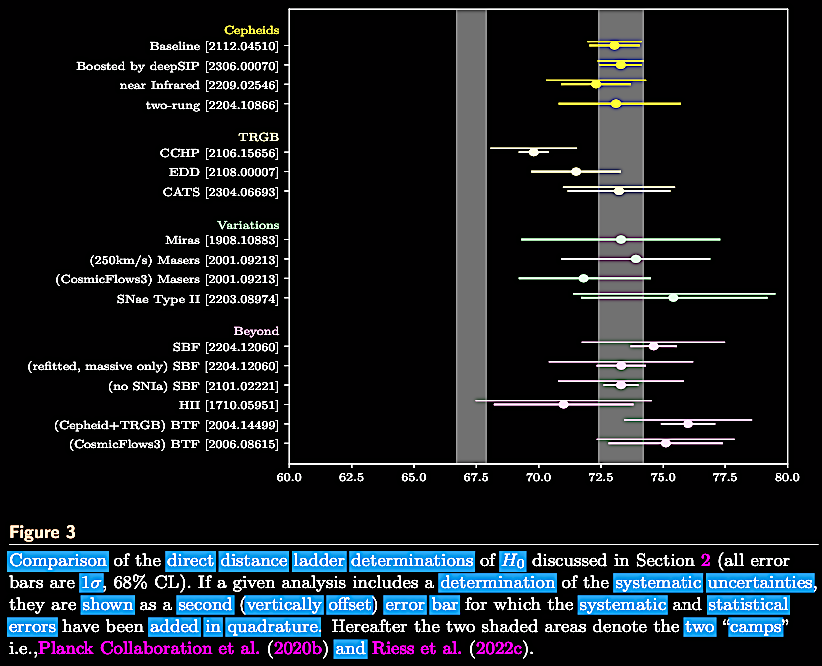

Over recent years, there has been a growing disagreement between estimating the Hubble constant, H0, using more local distance measures with (often a very few) 'standard candles' such as Cepheid variables and red giants (~72-73 or even 75 +/- 2.3, &c., km s−1 Mpc−1 ) and those estimated by supposedly early universe parameters of the CMB which are model-derived by the CDM and ΛCDM versions of the HBBC (~67-69 km s−1 Mpc−1 ; see citations on the disconnect controversy link, link, and link). Despite the above claims of approaching resolution between 'standard candle' and model-dependent estimates of H0, as of 2022, the discrepancies are gaping, as indicated in a selection of recent papers.

- For a few

examples, de Jaeger et al. (March 2022) in their

attempts to resolve the "Hubble tension" tried the

following: using

"13 SNe~II with geometric, Cepheid, or tip of

the red giant branch (TRGB) host-galaxy distance measurements"

derived H0

= 75.4 +3.8/−

3.7 km s−1

Mpc−1

(statistical errors only), which they claimed was "

consistent with the local measurement but

in disagreement by ~2σ from +ΛCDM value." Also, de

Jaeger et al. using Cepheid variables only

with a sample size of N = 7, arrived at H0

= 77.6 + 5.2/−

3.7 km s−1

Mpc−1

, and when using only red giants (TRGB) with a

sample size of N = 5, found H0

= 73.1 + 5.7/−

5.3 km s−1

Mpc−1

.

They further claim they did not find that the SNe~1e

or the Cepheids were the source of the "H0

tension" while admitting that their "conclusions rest

upon a modest calibrator sample," and urge that larger

studies be done in future (

arXiv:2203.08974).

- In April 2022, Cao & Ratra (2022) claimed to use non-CMB and "model-independent determinations" with " updated Hubble parameter and baryon acoustic oscillation data, as well as other lower-redshift Type Ia supernova, Mg II reverberation-measured quasar, quasar angular size, H II starburst galaxy, and Amati-correlated gamma-ray burst data, to jointly constrain cosmological parameters in six cosmological models," to arrive at H0 = 69.7 +/− 1.2 km s−1 Mpc−1 , " the flat ΛCDM model is most favored but mild dark energy dynamics and a little spatial curvature are not ruled out" ( arXiv:2203.10825).

- In March

2022, Hu & Wang (link) reported that the "Hubble

crisis" may be relieved by having H0

change over cosmic time from the

early universe to the present epoch

(arXiv:2203.13037).

Anand

et al. in March of 2022 instruct the reader to

"worry no more, the Hubble tension is relieved" because

they made local cosmic measurements using inferences

from sedimentary and eclipse-based data of the lunar

recession velocity to arrive at H0

= 63.01 +/−

1.79 km s−1 Mpc−1,

which they tout as the first single-step,

model-independent measure of the Hubble constant, which

also is not far from CMB and the ΛCDM model determinations, concluding that

local measurements are the source of the Hubble

tension (

arXiv:2203.16551).

- In April

2022, Liu et al. also claim a model-independent

cosmography method of directly measuring by

reconstructing distance based on cosmic chronometer and

gravitational lensing observations, as well as a

measurement of space-time curvature, while avoiding the

polynomial curve-fitting and what the polynomial

coefficients might physically mean: H0

= 72.24 +2.73/−

2.52 km s−1

Mpc−1

(arXiv:2204.07365).

When assuming a flat universe in advance, they arrive at

H0

= 70.47 +1.14/−

1.15 km s−1

Mpc−1

, between the Planck CMB and the SH0ES observations.

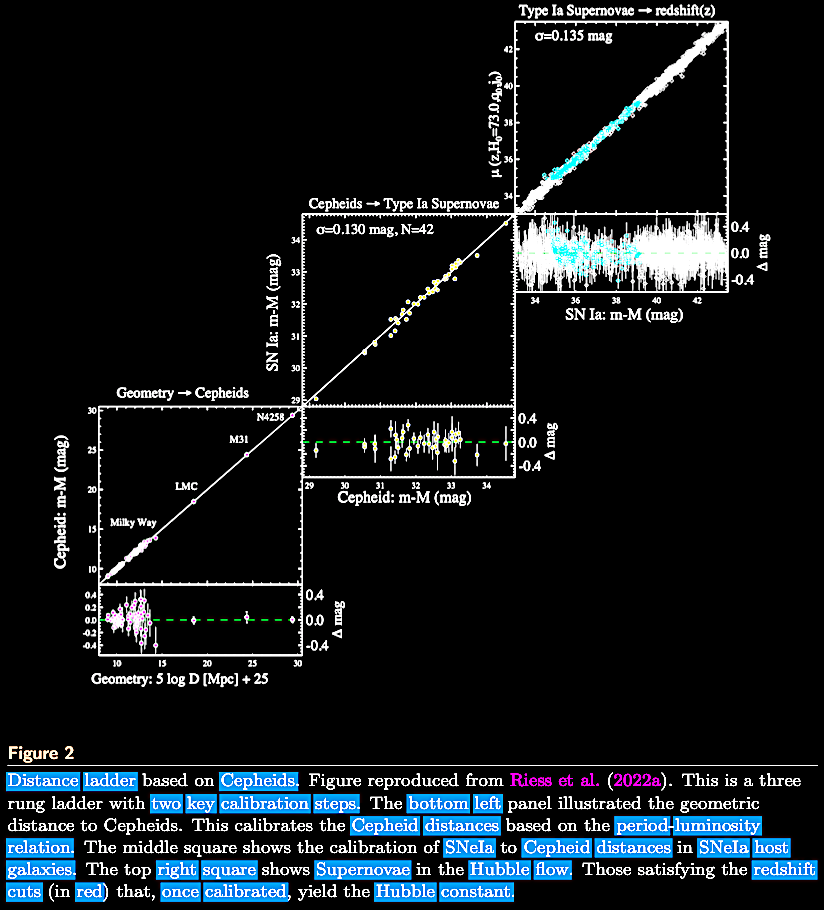

- In late April, the large group of Kenworthy et al. ( arXiv:2204.10866) used a 3 rung distance ladder of calibrating Type Ia supernovae using a SH0ES measurement for the host galaxies of 35 Cepheid variables at cz < 3300 km s−1 , geometrically calibrated in our Milky Way, NGC 4258, and the Large Magellanic Cloud (LMC), and arrived under various assumptions including peculiar velocities at z ~ 0.01 at a range of H0 = 71.8 to 77.0 km s−1 Mpc−1 . By combining the four best fitting selection models, they estimated H0 = 73.1 to 77.0 km s−1 Mpc−1 , which is 2σ removed from the Planck results.

- Also in April

2022, Garnavich et al. (

arXiv:2204.12060)

compared infrared surface brightness fluctuations (IR

SBF) in galaxies hosting type Ia supernovae (SNIa) to

distances estimated by SNIa light curve fitting, showing

that IR SBF estimates are different from those derived

from Cepheid variable calibrators. Using IR SBF results

from massive galaxies surveye within ~100 Mpc by Jensen

et al. (2021;

arXiv:2105.08299), Garnavich and

colleagues arrived on basis of 25 SNIa host galaxies at

H0

= 74.6 +/−

0.9(stat) +/−

2.7 (syst) km s−1

Mpc−1

,

including both statistical errors and systematic errors,

and thus consistent with supernovae distances calibrated

with Cepheids.

- In early May

2022, Renzi and Martinelli (

arXiv:2205.03396)

propose that using super massive black hole (SMBH)

shadows on galaxies as a distance anchor in the distance

ladder, in place of Cepheids for example, will be able

to constrain H0

values within

H0

≈ 10% for

current ground

based

interferometers

and within H0 ≈ 4% for

future interferometers.

- Another team in May 2022, Breuval et al (including Adam Riess; arXiv:2205.06280) added an improved calibration for the wavelength dependence of metallicity on the Cepheid Leavitt law, and cepheid brightness does depend on metallicity. Why such a calibration needs to be done of course drops a hint indirectly that other factors need to be taken into account when considering galactic redshift, not limited to be a result of space-time expansion. (More on that).

- Reviewing

developments, Blanshard et al (

arXiv:2205.05017)

in May of 2022 reviewed the tensions in the measurement

of H0

and

estimates of matter density within the ΛCDM and

some "alternative cosmological models" (CDMs without Λ) highlighting the

tensions. They say that data on cosmic chronometers

allow derivation of an accurate value at H0

= 67.4 +/−

1.34 km s−1

Mpc−1

.

Nevertheless, they came to the conclusion that

the ΛCDM model is "alive

and well"

but has "an unknown bias in the Cepheids distance

calibration" and celebrate a remarkable agreement for

the model, statistically better than the previously

proposed extensions with H0

~ 73.

- In late May

2022, Chen et al (

arXiv:2205.11278)

arguing that gravitational waves (GW) are another way to

probe the Universe's expansion history, and adopt the

assumption that binary black hole (BBH) coalescent

events involve black holes detected by LIGO-Virgo-KAGRA

(LVK) collaboration are primordial in origin, using 43

BBH events from the third LVK GW transient catalog

(GWTC-3). Using three PBH mass models and some Bayesian

population analysis, they concluded that the constraints

on the ΛCDM model

cosmological parameters "are rather

weak and in agreement with current

results." When combining in

a measurement from GW170817 (a LIGO / Virgo GW signal of

merging neutron stars detected in 2017 in NGC 4993),

they were able to claim constraint of H0

between

69 +19/−

8

km s−1

Mpc−1

and 70 +26/−

8

km s−1

Mpc−1

,

comparable

with results

from

phenomonological

models of

astrophysical

mass models of

BH

coalescence.

- In mid May 2022, Schiavonne et al ( arXiv:2205.07033), in examining a collection of 1048 Type Ia Supernovae (SNe Ia) in the Pantheon sample database with a redshift between 0 < z < 2.26, looked to see if the H0 tension may be found among SNe Ia data using binned statistical analysis with the MCMC method for each bin, considering the ΛCDM and the w0waCDM cosmological models. They observed that H0 evolves with redshift using a fitted function, H0(z) = ~H0(1 + z)− α where ~H0 and α are two fitting parameters. Extrapolating with ~H0 back to the redshift of the last scattering estimated to be about z = 1100, where they obtain values of consistent with 1σ of the Planck CMB estimates of H0. So much for heavily model-dependent parameter fitting. However, they do discuss modified gravity models to explain the redshift varying Hubble constant, and make inferences about the postulated involvement of a scalar field potential.

Since

JWST. Since becoming fully operational in July of

2022, JWST has not resolved the questions. Just within the

arXiv database, a non-quote restricted query for 'measuring

the Hubble constant' continues to illustrate the ongoing

tensions within and beyond the >CDM paradigm for

determining H0

(1,927 results by 30 May 2024: arXiv

query; 1,920 results without 'the': arXiv query). In the more

restricted case of the quote-restricted phrase "Hubble

tension" query we have 612 results (30 May 2024: arXiv

query), whereas for the non-quote-restricted

phrase 'Hubble constant' we have 1,386 results (30 May

2024: arXiv

query). There is a large burgeoning of attempts to

resolve this tension.

Questions: Is the Hubble

tension caused by artifacts of instrumentation in

different data cohorts? Or is there a paradigmatic

reason why such a tension exists? On 28 May 2024,

physicist / physics (sometimes cosmology) popular

commentator, Sabine Hossenfelder on her YouTube channel

suggested that "A huge cosmology problem just might have

disappeared" (videolink)

citing the November of 2023 paper, which we discuss

further by Freedman, W. L. & Madore, B. F. (2023).

Progress in direct measurements of the Hubble constant.

Journal of Cosmology and Astroparticle Physics (JCAP)

2023, 1-35. JCAP11(2023)050. https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.1088/1475-7516/2023/11/050/pdf.

https://doi.org/10.1088/1475-7516/11/050.

Hossenfelder frames the issues succinctly by noting that

the Hubble tension is caused by one (any) of the

following:

- 1. Measurement error—in either the

direct redshift measurements using supernovae,

Cepheids, red giants, &c. distance ladder or the

indirect CMB redshift measurements to determine H0.

- 2. Data analysis—how the measurement

data of these competing data sets are analyzed.

- 3. Problem with the model—the

assumptions of homogeneity or isotropy of the

Universe, the distribution of mass-energy and

structure, &c.

- 4. Problem with the theory—that is,

with the field equations of general relativity,

which can vary depending on whether you are using a

'black hole' or 'bulging disk' approach. And now,

let's also add....

- 5. Perhaps the whole paradigm of the

HBBC itself needs to be re-evaluated.

In chapter

V, we discuss the Freedman & Madore (2023)

paper, the data, analyses, results, and the implications

for cosmology.

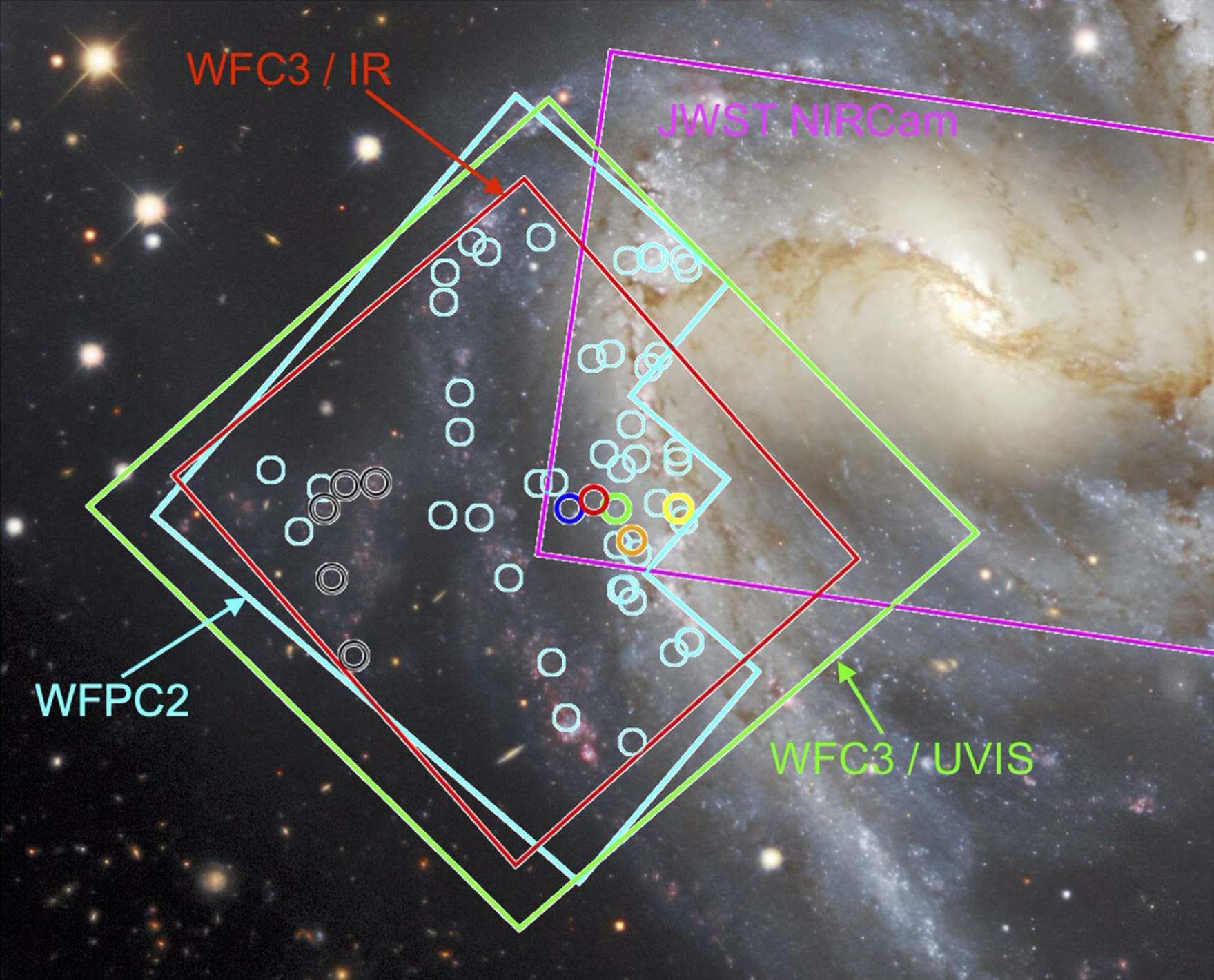

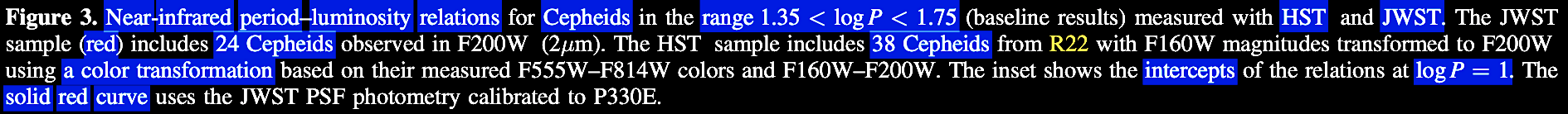

Question

for JWST: Has the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST),

which became operational in July of 2022, helped this

'tense' situation any? According to a report from November

of 2022, Yuan et al. [including 'dark energy' Nobel

laureate Adam Riess] (2022. A first look at Cepheids in Type

Ia supernova host with JWST. ApJ Letters 940,

L17. https://doi.org/10.3847/2041-8213/ac9b27),

they found that although not fully optimized for Cepheid

observation, with JWST's higher sensitivity in the near-IR

part of the spectrum, they were able to mitigate host

dust-dimming effects on distance estimates from Cepheid

variables in NGC 1365 the host galaxy for distance

calibration of SNIa 2012fr for the Hubble constant (H0).

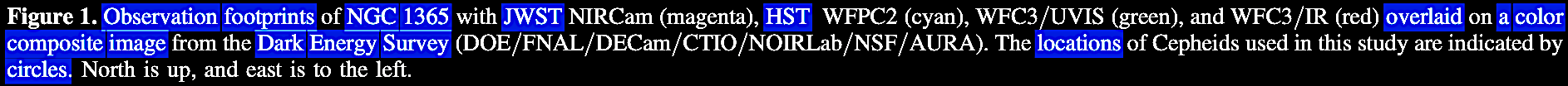

Using a standard star, they did photometry on 31

previously-assayed Cepheids with JWST spanning the period

(P) interval from 1.15 < log P < 1.75

including 24 Cepheids with longer P range of 1.35 < log P

< 1.75. The period-luminosity (P-L) relations of this

cohort was compared to the HST photometry results from 49

Cepheids in the full period range as well as 38 in the

longer-period interval. HST and JWST results respectively

show good agreement on P-L relations with intercepts (at log

P = 1) of magnitudes of 25.74 +/- 0.04 and 25.72 +/-

0.05. The HST-JWST Cepheid photometric consistency shows

that there's no HST-'biased-bright' error at the ~0.2

magnitude level which was suggested as a resolution to the

'Hubble tension.' See Yuan et al.'s

Figures 1 and 3 below.

Answer: No. The 'Hubble

tension' is left unresolved because it is not an

artifact of method or instrumentation, but a real

feature of the data sets, which again suggests the need

for a paradigmatic shift in cosmological theory. The

data collected from the world's next generation space

observatory, the JWST, is helping in that

direction.

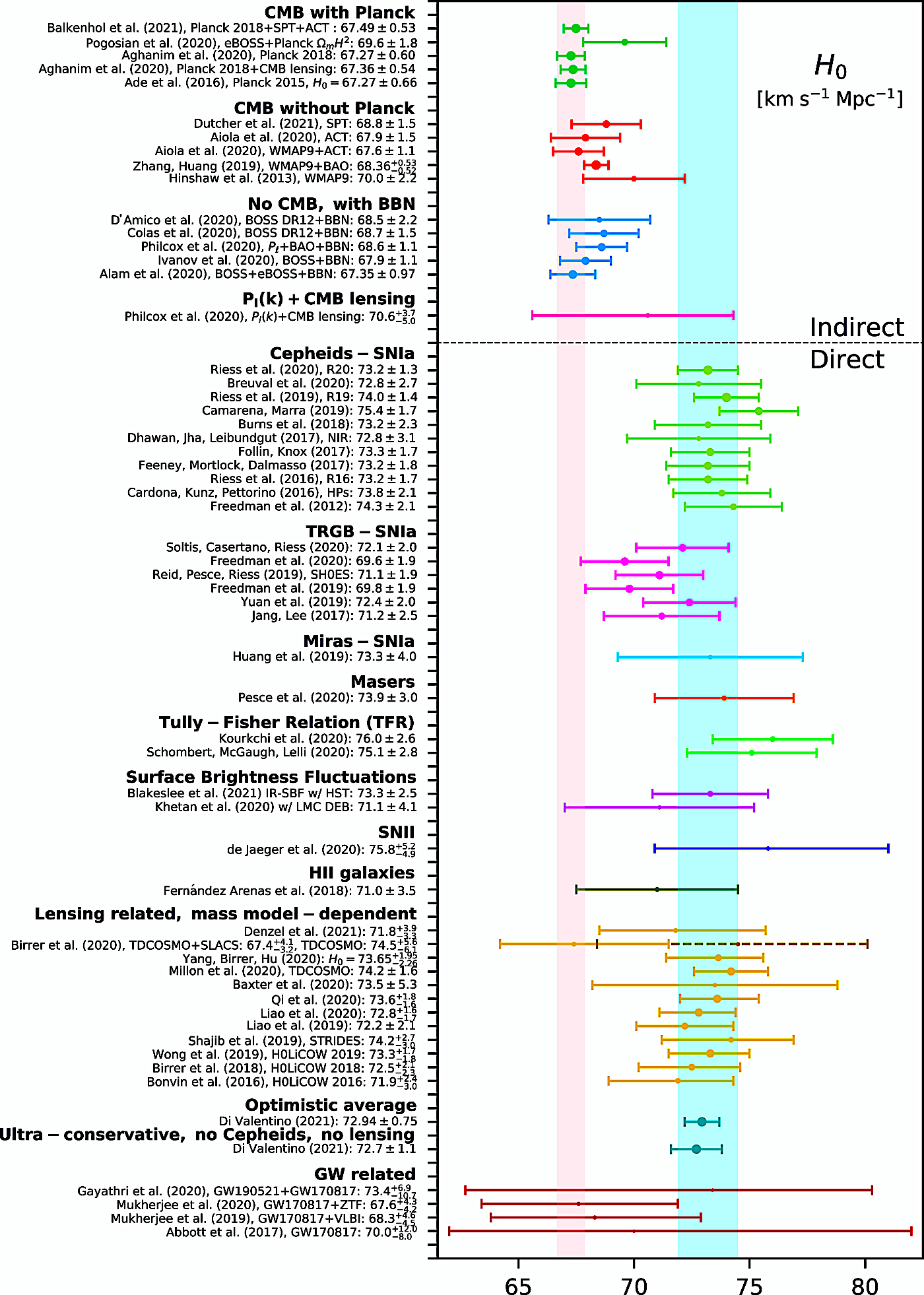

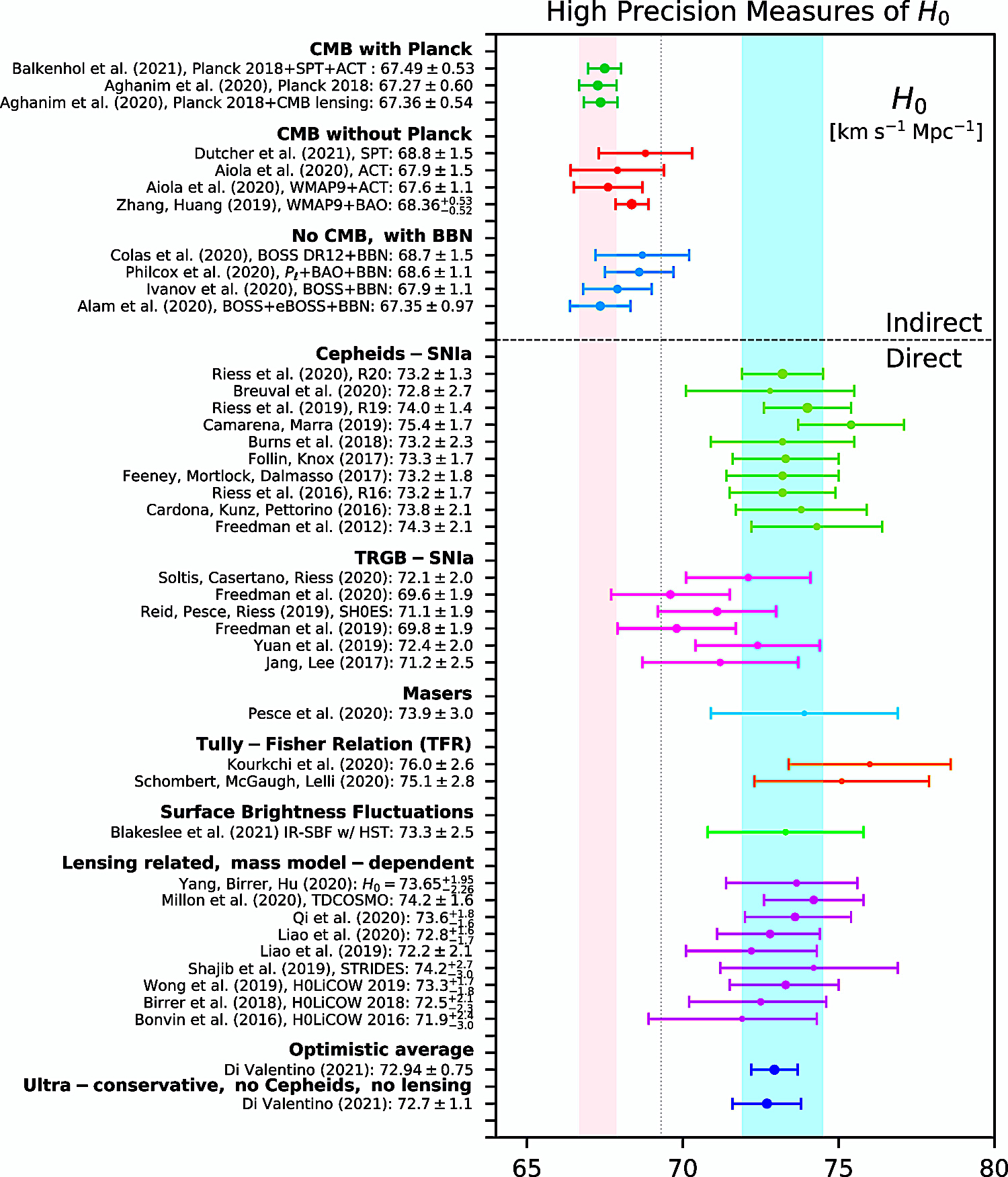

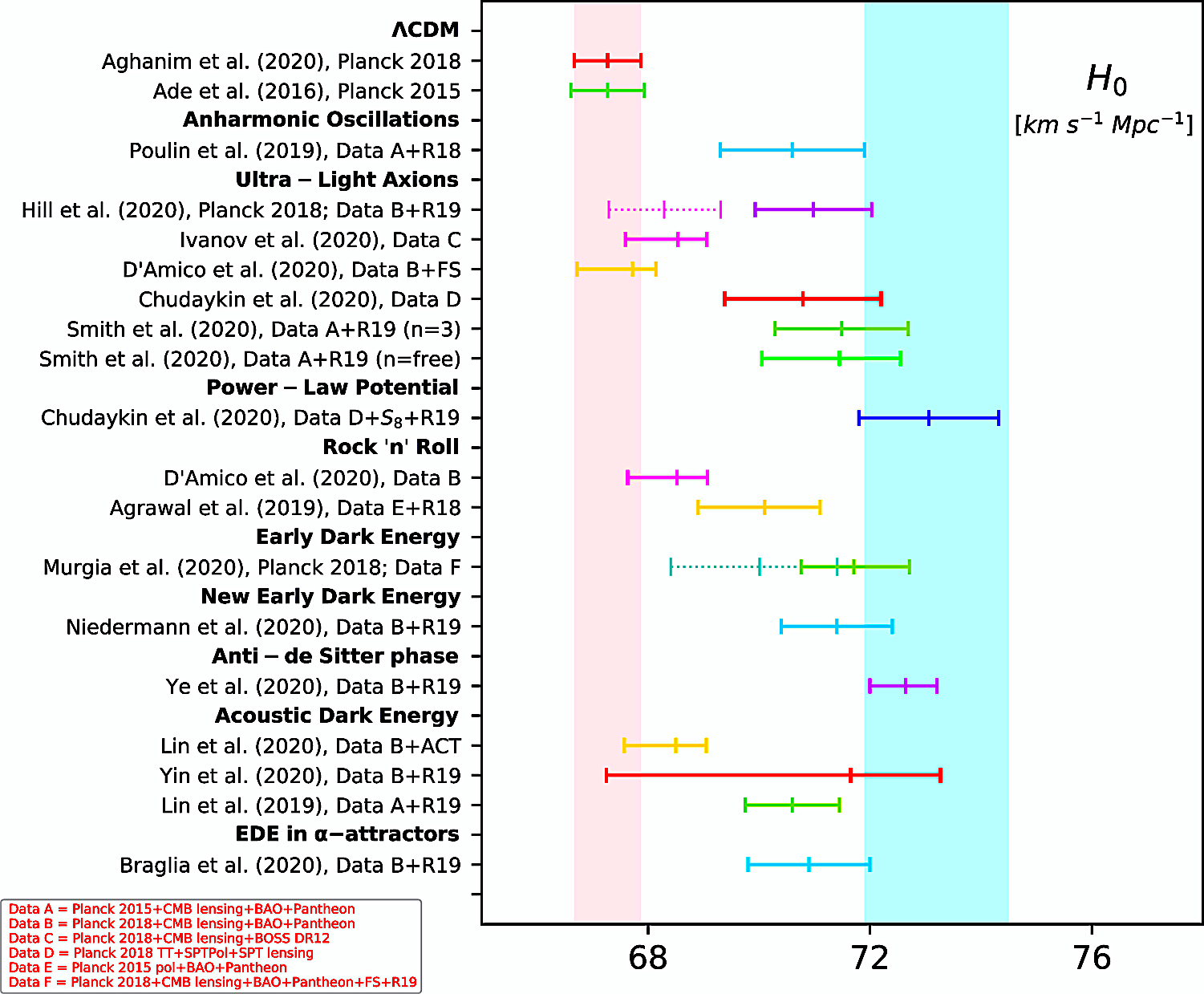

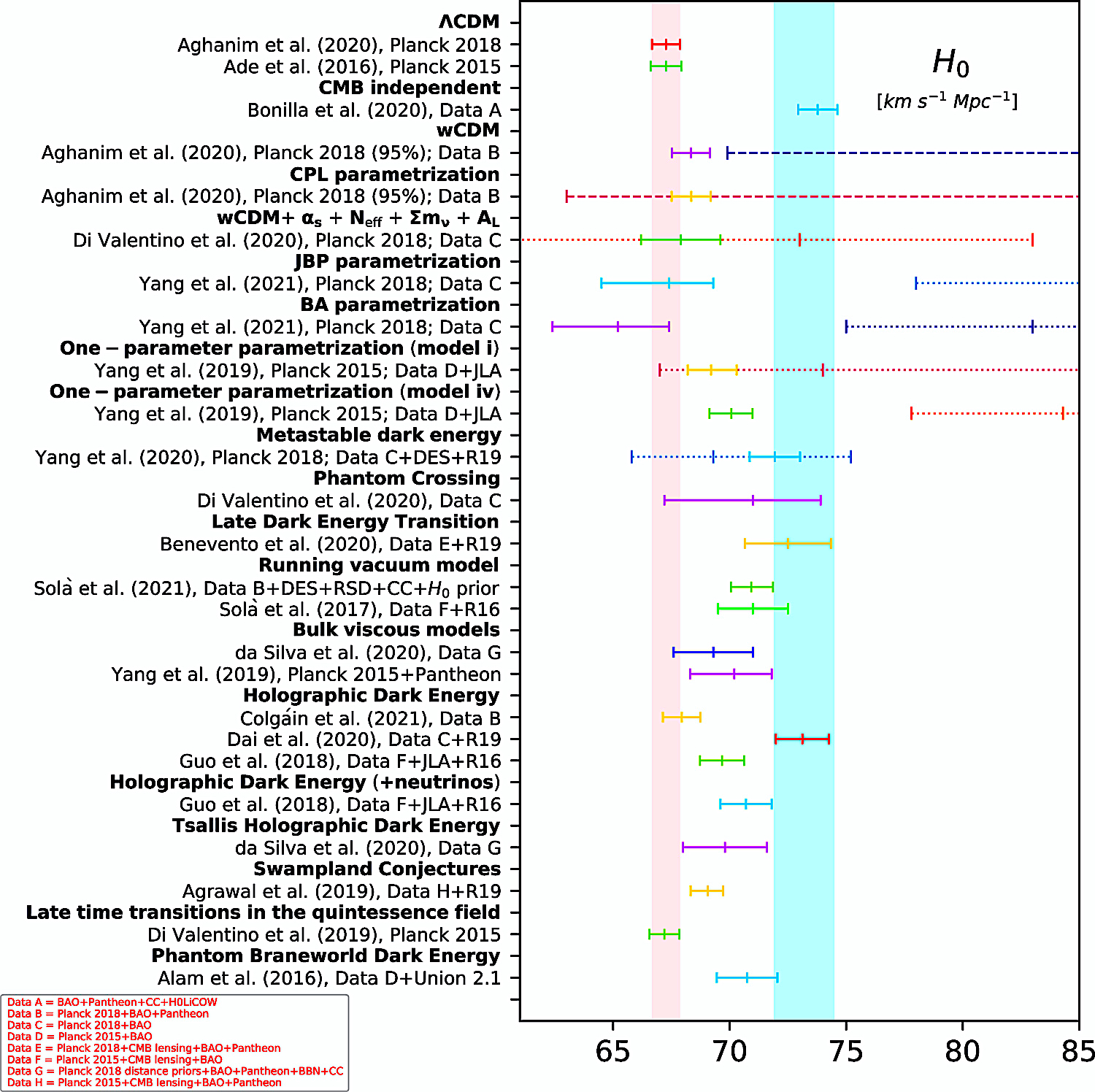

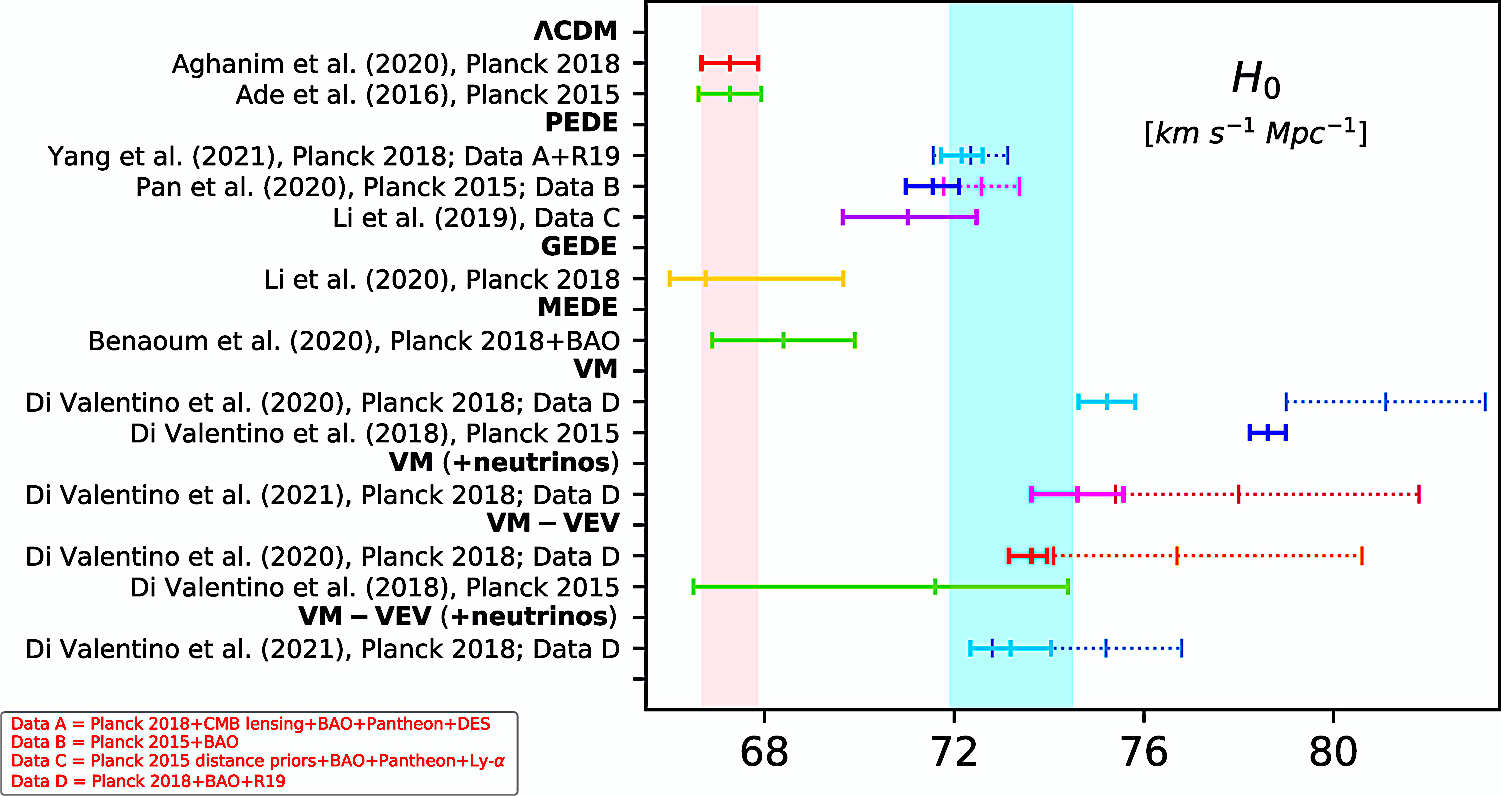

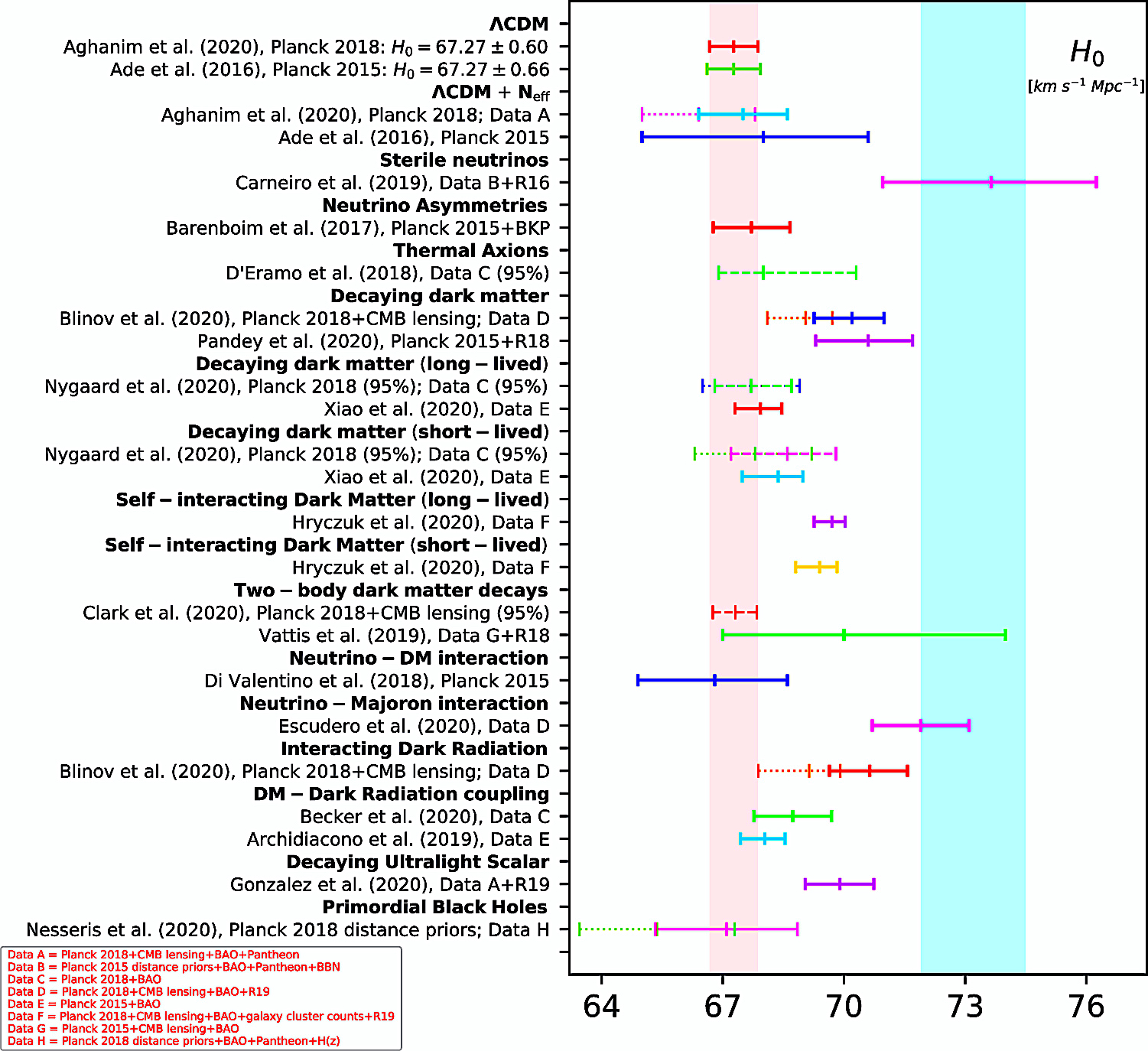

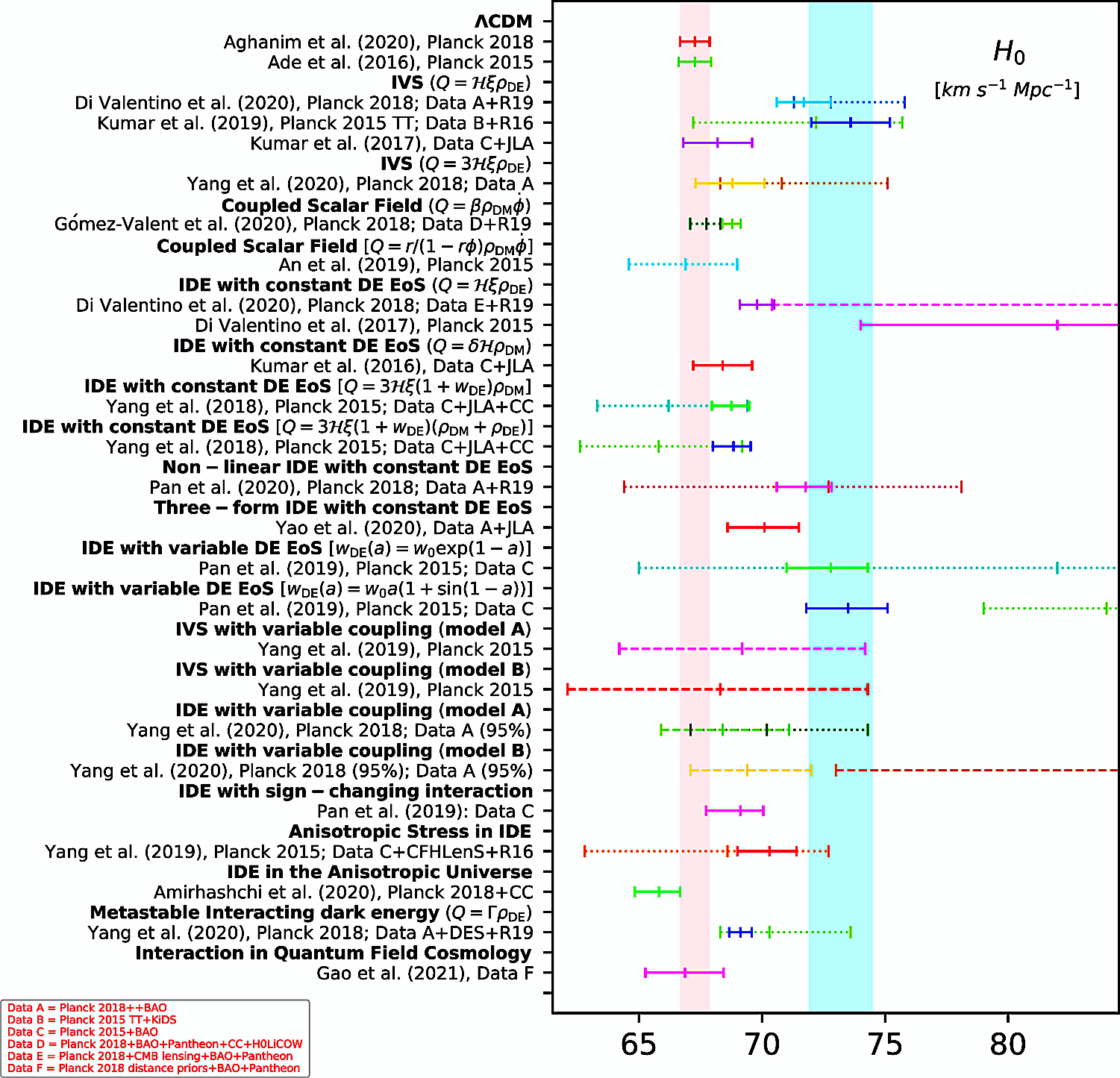

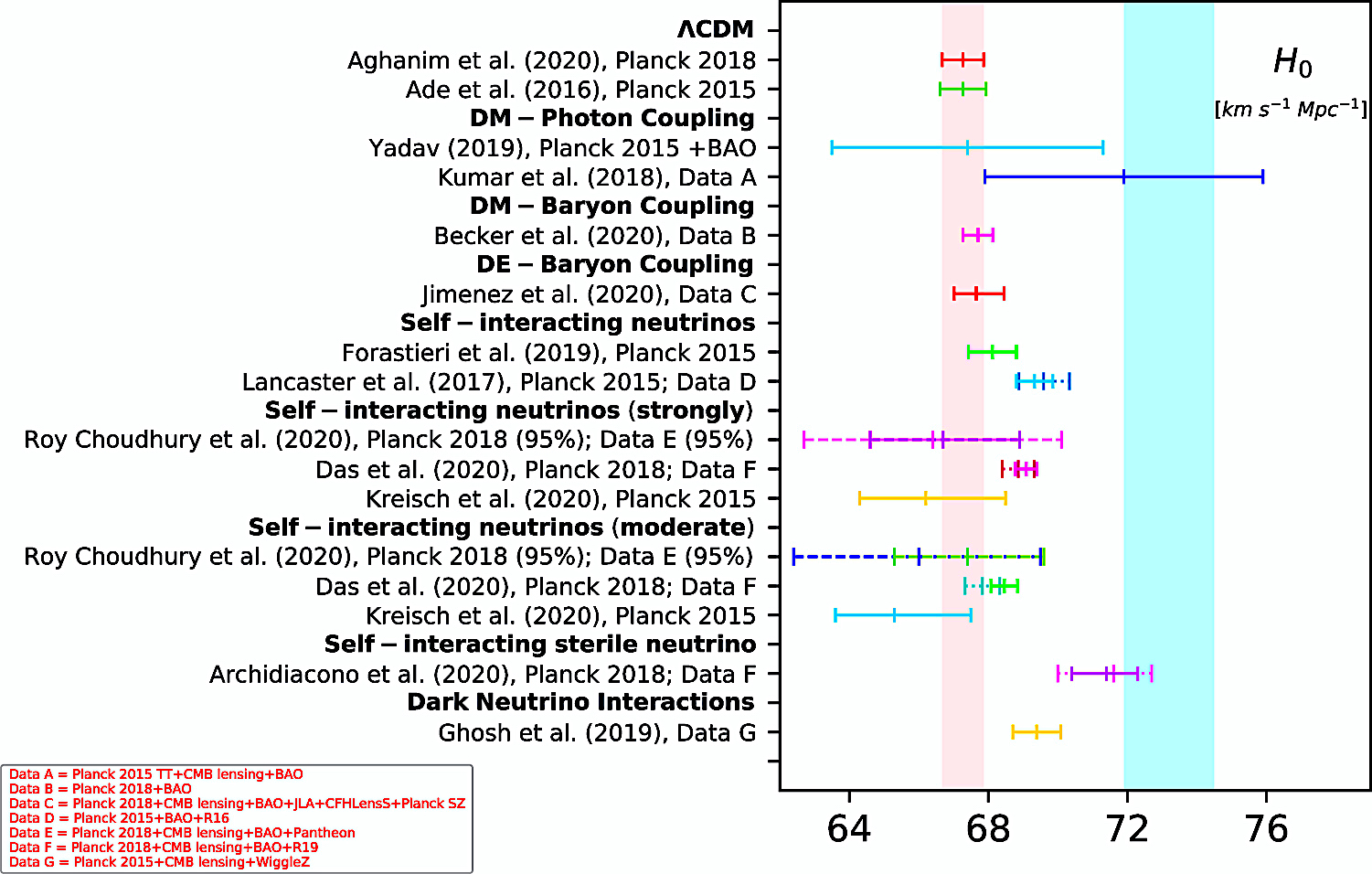

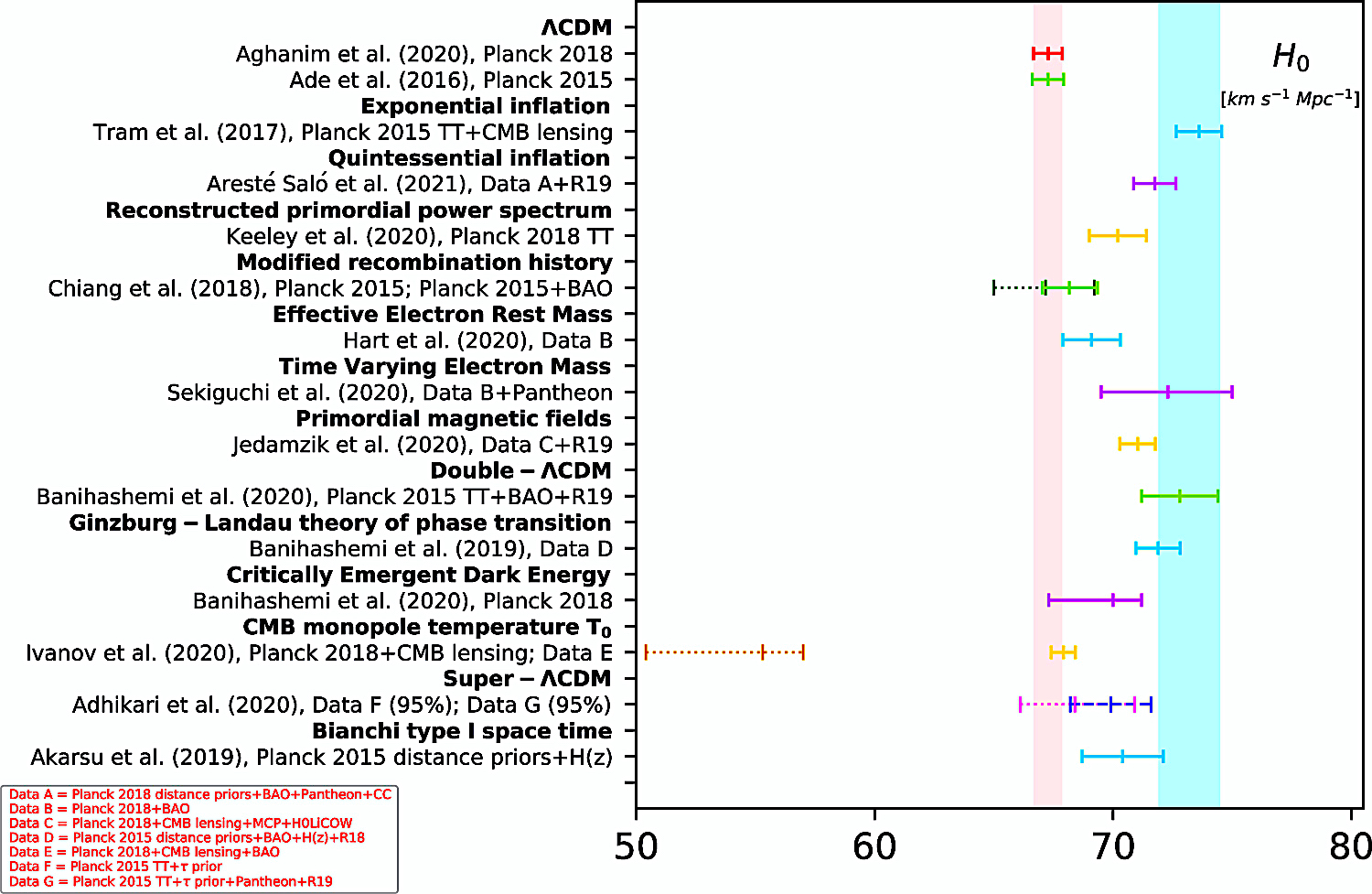

Back in 2021, Di Valentino et

al. (with an author line including 'dark energy'

Nobel Laureate Adam Riess and grand master astronomer

Joseph Silk) published a 110 page monograph reviewing

>1000 peer-reviewed papers with a title parroting

Edwin Hubble's famous 1936 book title, "In the realm of

the Hubble tension—a review of solutions" in Class.

Quantum Grav. 38, 153001 (https://doi.org/10.1088/1361-6382/ac086d).

For their comparison standards, Di Valentino et al.

compared this multitude of papers to the Planck 2018 cosmic

microwave background power spectrum data with baryonic

acoustic oscillations (already loaded with adjustable ΛCDM

parameters and yielding an H0

value centered on 67.36 +/- 0.54 km s−1 Mpc−1,

according to Hart & Chluba, 2019) and

the combined Pantheon SN1e

and latest R20 data from the SH0ES Team Riess et al.

(2021, Astrophys. J. 908, L6) with an

extrapolation of the Hubble constant, H0

= 73.2 +/- 1.3 km s−1 Mpc−1 at the 68%

confidence level (CL). Like the Planck 2018 data, the SH0ES data set is itself heavily

parametrized as indicated in the mere meaning of the acronym

itself, "Supernova, H0,

for the Equation of State of Dark Energy"

(ESA press

release on the 2001-2021 SN data). Excerpted from the

many figures of the H0

values in studies cited in the monograph, one can see the

vast degree of parameter-fitting or epicycles-upon-epicycles

inserted to try to resolve this supposed constant considered

a holy grail of modern cosmology. Even with all of the

multitude of attempts to adjust parameters or create

epicycles, create complex new models, some appealing to

unknown physics, there still is a 4

σ discrepancy between these two

standards, or euphemistically we can call it a mere

'tension':

In the excerpted whisker

plots from select figures (di Valentino et al. 2021):

The vertical pink band equates with the H0 value reported by

the Planck 2018 team "within a ΛCDM scenario," while the

vertical cyan band equates with the 68% CL estimation of the

value based the SH0ES R20 data

Fig. 1 (di Valentinto et al. 2021).

Fig. 2 (di Valentinto et al.

2021).

Fig. 4 (di Valentinto et al. 2021).

Fig. 6 (di Valentinto et al. 2021).

Fig. 8 (di Valentinto et al. 2021).

Fig. 10 (di Valentinto et al. 2021).

Fig. 12 (di Valentinto et al. 2021).

Fig. 14 (di Valentinto et al. 2021).

Fig. 16 (di Valentinto et al. 2021).

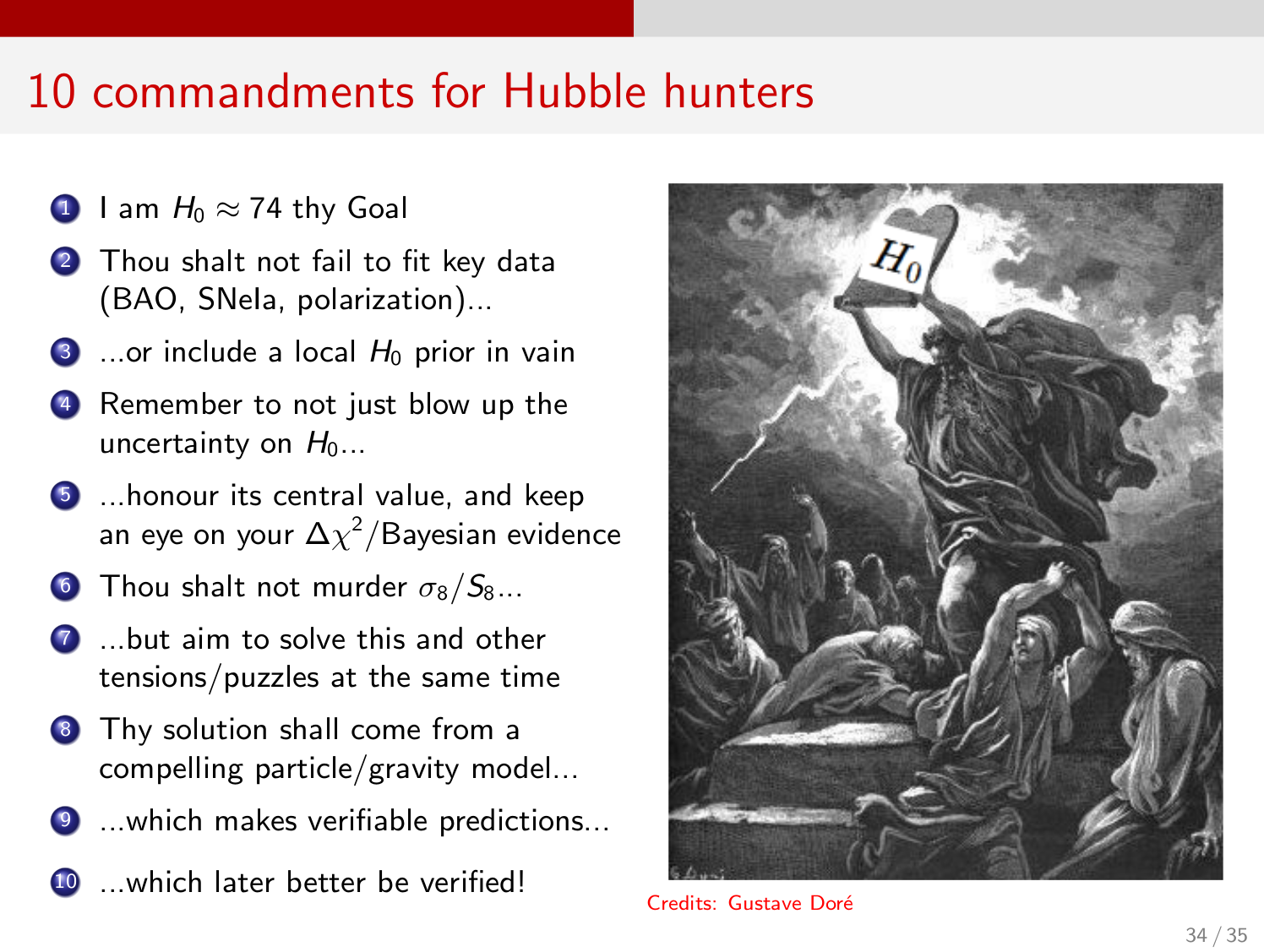

In

the spring of 2021, in a blog

entitled, "What is the Hubble tension, really? A

SH0ES-centric view of the problem," fellow at the Kavli

Institute of Cosmology (University of Cambridge), Sunny

Vagnozzi posted a humorous "10 commandments for Hubble

hunters" satirizing the parameter-fitting required for those

seeking to resolve the Hubble "tension." Here is the

original version, before he softened and euphemized the "4th

commandment" for a visiting lecture:

(https://www.sunnyvagnozzi.com/blog/what-is-the-hubble-tension-really).

What's

with the Hubble Constant determination Indeterminacy? What

is going on with the notorious difficulty of nailing down a

consistent, across the galactic constituent population and

across cosmic time value of H0?

Is it because H0?

varies over cosmological time?

Or is it because too narrow a

sample of 'standard candle'

bodies and the heavily

cosmological model-dependent

CMB-based calculations of H0.

What are they missing in the

cosmological data?

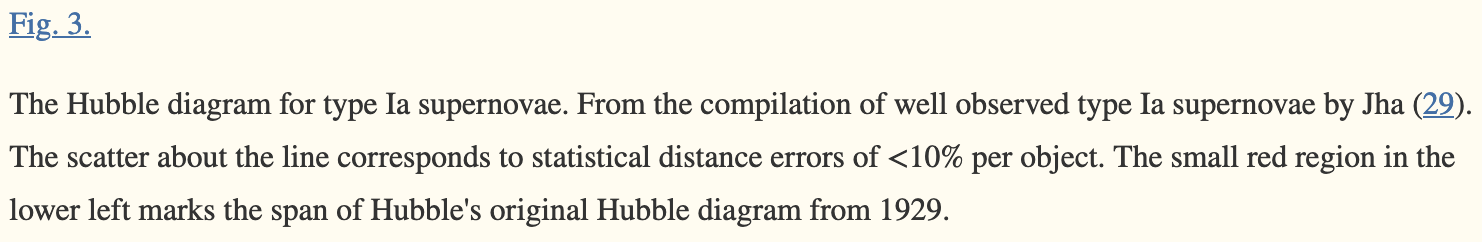

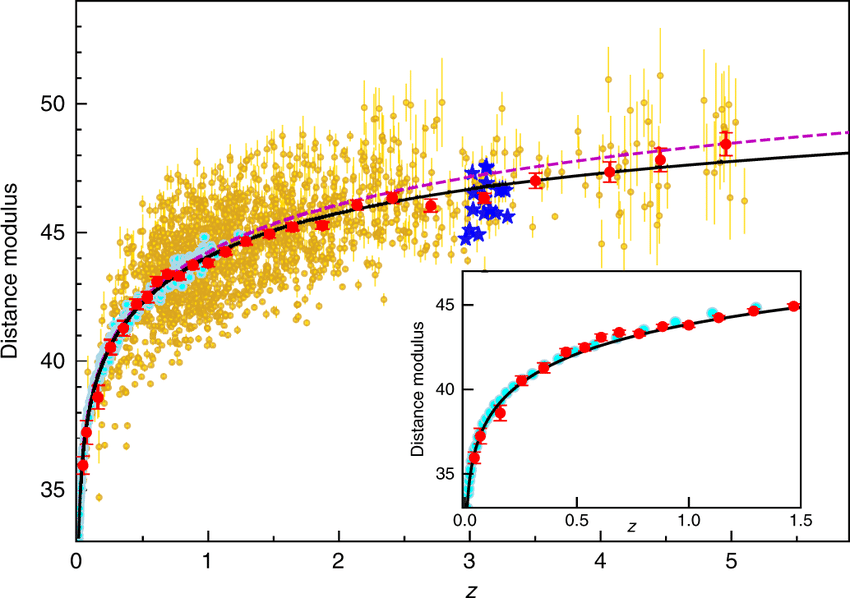

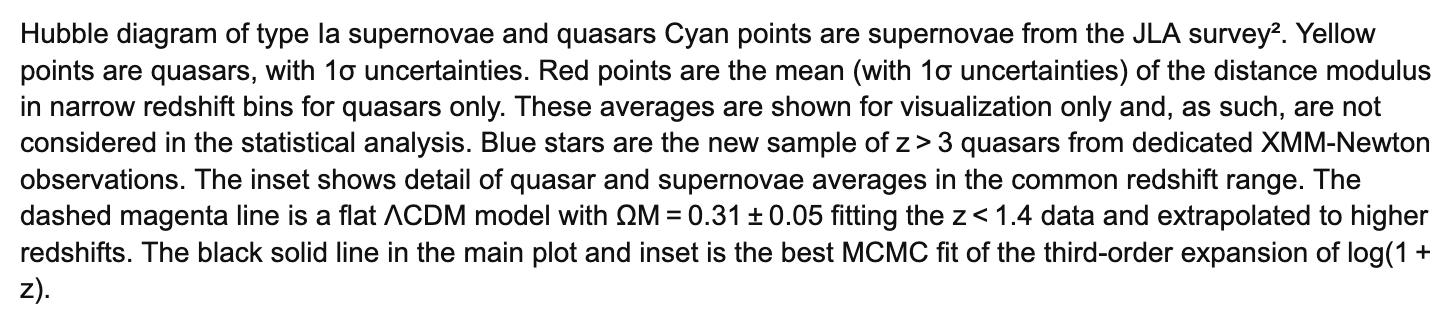

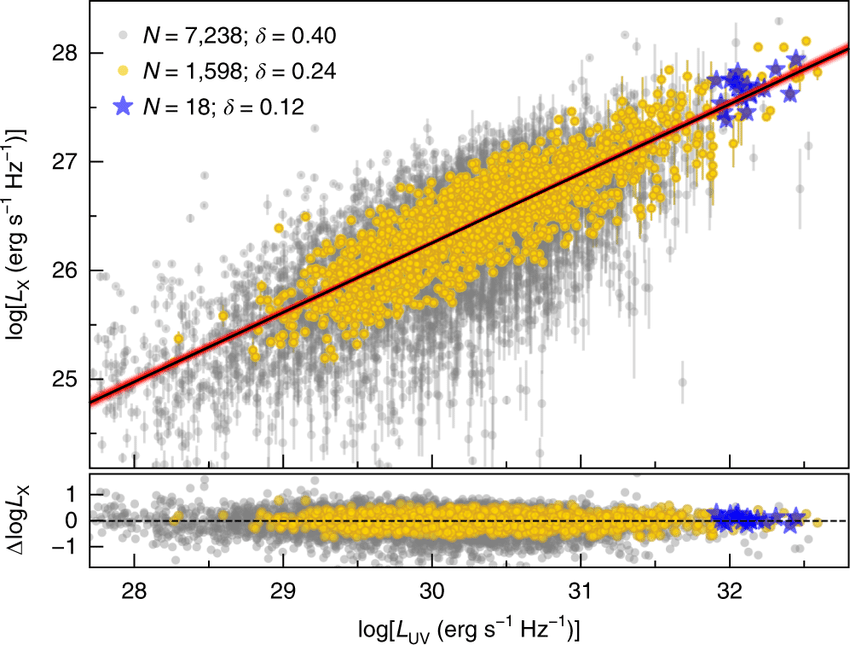

This

following diagram from Risaliti & Luzzo (2019;

DOI:10.1038/s41550-018-0657-z) further

illustrates the actual diversity of redshift / estimated

distance modulus with error bars in the data (including

~1600 quasars marked in yellow just with 1σ

uncertainties,

or the new

[blue-starred

marked]

quasars with z

> 3 from

the JLA

survey),

all illustrating much more redshift-diverse populations of

extragalactic objects. When set distance ladder 'standard

candle' are not the only objects included, then it becomes

obvious that the H0

relation values are not nearly so tightly

constrained as the HBBC model suggests, let alone the

highly-parameter-fitted CDM versions.

Figure legend

Figure legend (link).

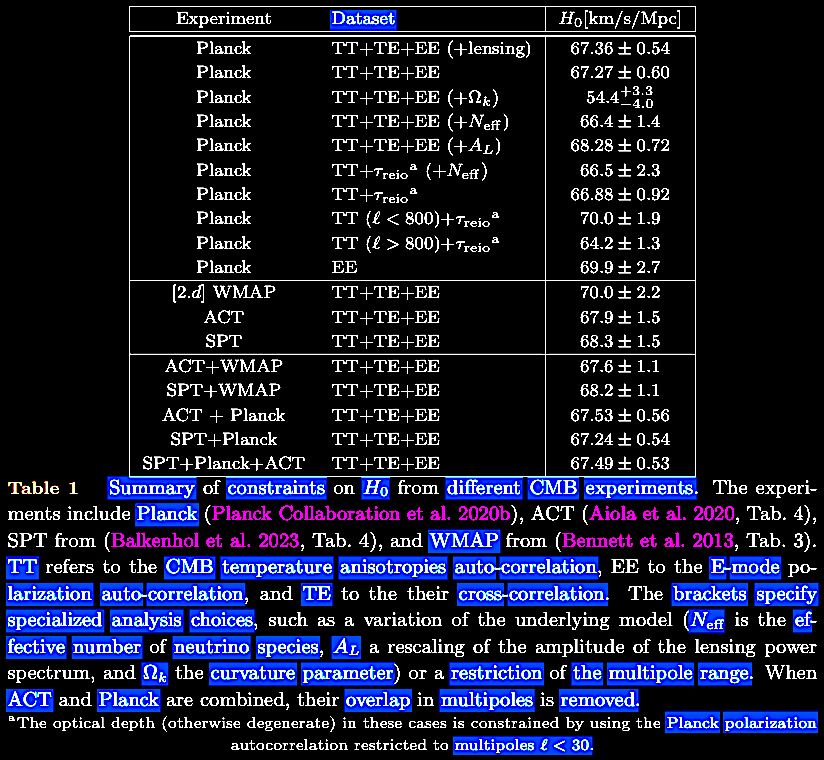

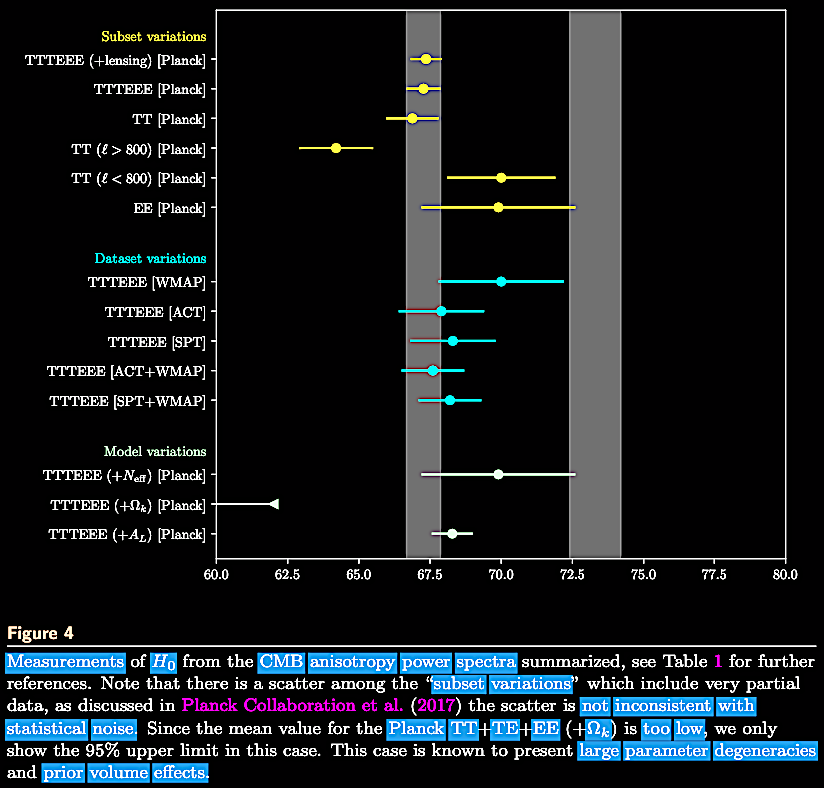

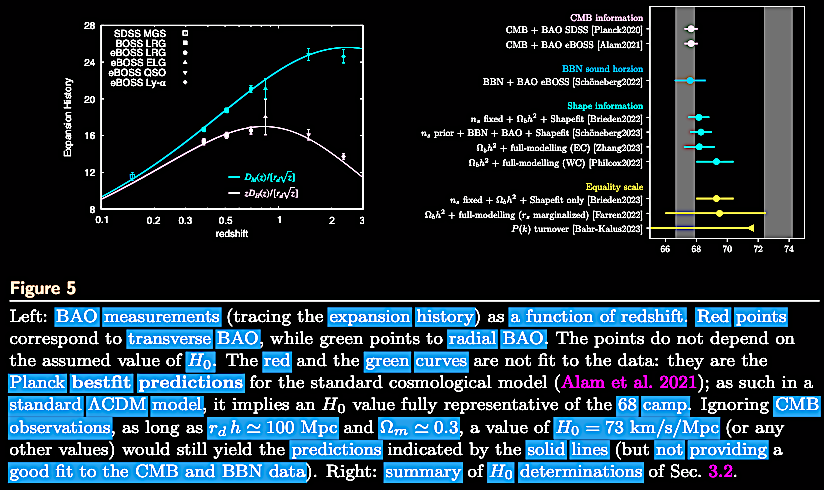

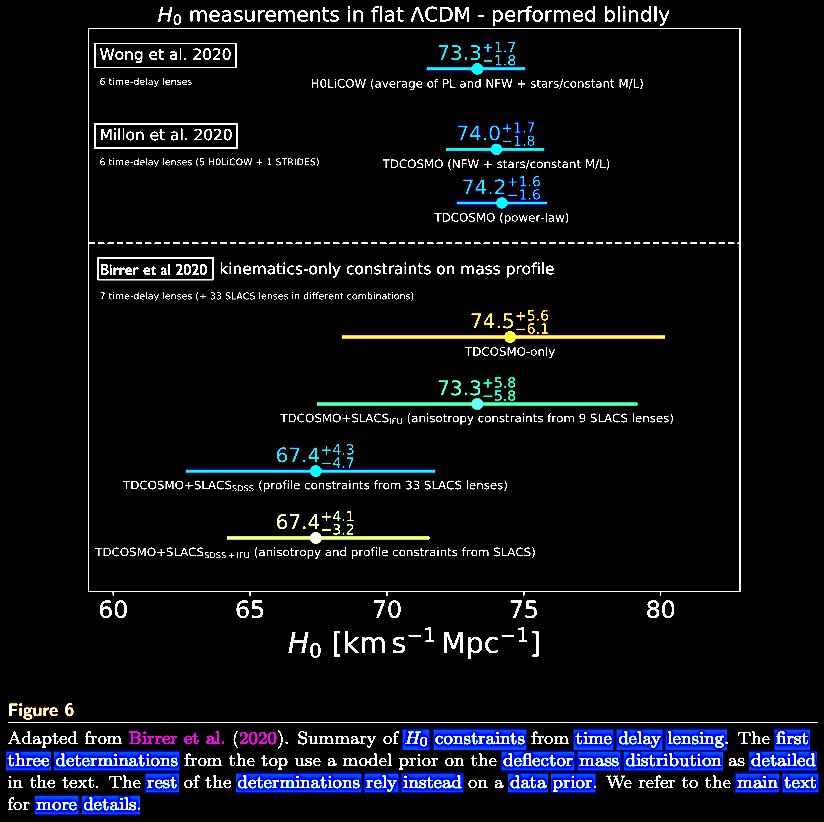

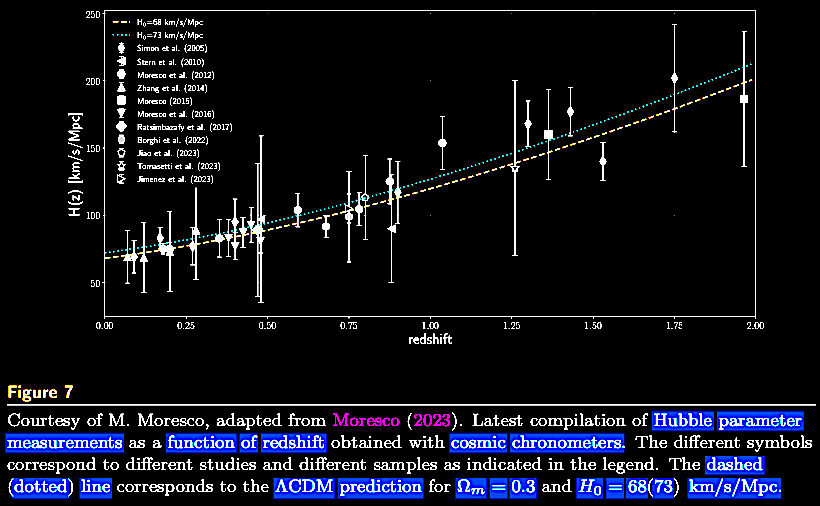

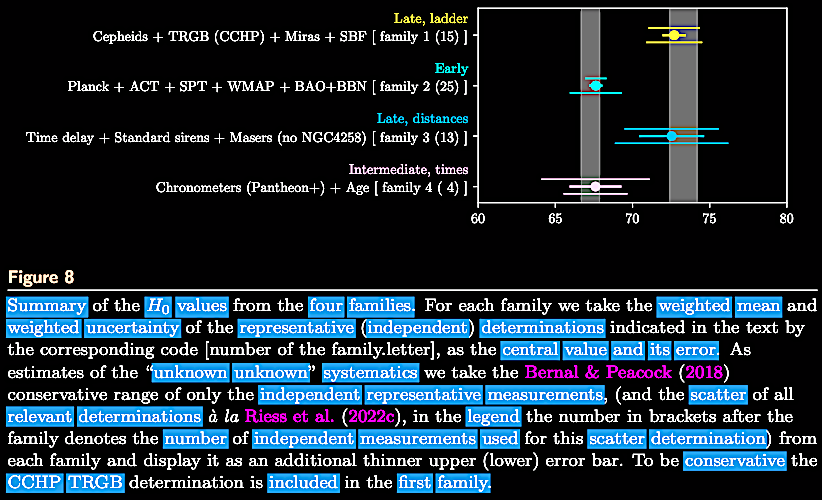

On 22 November 2023, Licia Verde, Nils Schöneberg, & Héctor Gil-Marín released a review paper on the status and meaning of the 'Hubble tension' and attempts to measure and account for it in the quest for a precision cosmology: Verde et al. 2023. A tale of many H0. https://arxiv.org/abs/2311.13305; https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2311.13305. The authors point out that there are two values around with the measurements cluster: (a) the model-independent determinations from nearby galaxies with standard candles like Cepheid variables and SNIa distance ladder data of H0 = ~68 km s–1 Mpc–1 and (b) the ΛCDM model-dependent determination of H0 = ~73 km s–1 Mpc–1 based on the CMB (for a discussion of the CMB and its interpretation in cosmology, see the yet-to-be-published Chapter IV. The Cosmic Microwave Background (CMB) radiation: From Where and Whence? "As far as the eye can see?"). They suggest that there are three ways to resolve the 'tension' none of which bring consensus to the research community:

- The first is to search for systematic errors of interpretation, i.e., the systematics of the distance ladder. If those are missing, then the ΛCDM model needs modification and there are only two ways to 'fix' it:

- (i) By altering the

physics of the early time (z ≳ 1100) and "thus

the early time normalization" of the ΛCDM or

- (ii) By making "a

global modification" of the model, including questioning

the model’s basic assumptions such as the homogeneity of

the Universe, the isotropy of the Universe, and the

gravitational model of the cosmology.

|

|

|

TT = temperature power..., TE = temperature-polarization cross..., & EE = polarisation power spectra, respectively. |

BAO = baryonic acoustic oscillation. |

|

|

|

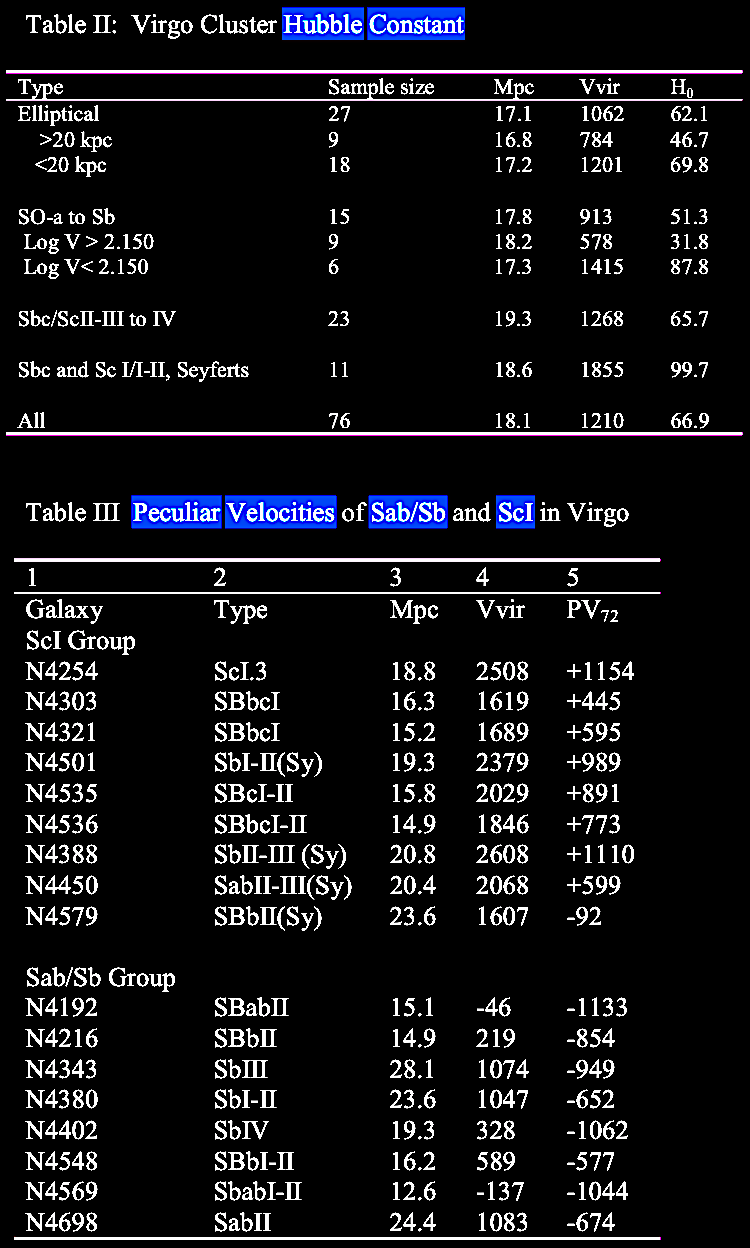

Redshift anomalies: Long before the current 'Hubble tension'

Long before the ongoing 'Hubble tension' crisis in cosmology, in fact decades before a series of unexpected, non-HBBC-canonical galactic redshift anomalies began to surface, quite prior to the various 'fixes' of added epicycles to the ΛCDM version of the HBB cosmology, suggesting that something is going on which not only does not fit the HBBC in general, but has never been directly dealt with in dominant ΛCDM hot Big Bang cosmology (HBBC). We will be returning in several chapters (VIII, IX, and X, as well as possible remote JWST-discovered redshift associations in chapter V) to the subject of anomalous redshifts.

Unexpected redshifts: The complicated nature of galactic redshifts. The early start of the real problem arose when the proponents of the HBBC paradigm narrowed their focus and research to simply trying to determine and then refine "the value H0" by selected from the diversity of object-specific redshifts or z-values in any given cluster or supercluster of galaxies, rather than examining all the redshifts in any clusters and superclusters under survey to see if there are perchance any issues affecting the H0 redshift relation.

In the mid-1960s, a series of discussions stirred up by CSSC-associated cosmologists questioned whether the QSOs and their redshifts fit well into the distance-luminosity H0 models. In a pitched 'battle' between: Hoyle, F. & Burbidge, G. R. 1966. Nature 210, 1846; Hoyle. F. & Burbidge, G. R. 1966. ApJ 144, 634; and Hoyle, F., Burbidge, G. & Sargent, W. 1966. On the nature of the Quasi-stellar Sources. Nature 209, 751. https://doi.org/10.1038/209751a0, and their Big Bang interlocutors, Longair, M. 1966. Evidence on the evolutionary character of the Universe derived from recent redshift measurements. Nature 211, 949. https://doi.org/10.1038/211949a0; Sciama, D. & Rees, M. 1966. Cosmological significance of the relation between red-shift and flux density for quasars. Nature 211, 1283. https://doi.org/10.1038/2111283a0; Roeder, R. O. & Mitchell, G. F. 1966. Nature 212, 166; and Bolton, J. 1966. Identification of radio galaxies and Quasi-Stellar Objects. Nature 211, 917. https://doi.org/10.1038/211917a0. In their letter to Nature, Hoyle, F. & Burbidge, G. 1966. Relation between the red-shifts of Quasi-stellar Objects and their radio magnitudes. Nature 212, 1334. https://doi.org/10.1038/2121334a0, pointed out that these critics had misrepresented them, and jumped the gun to conclude that the QSO redshifts supported an evolutionary model (short hand for Big Bang cosmology). Sciama & Rees (1966) had gone so far as to say that the QSO redshift data ruled out the steady state (CSSC) cosmologies. As with Martin Ryle's early claims in the late 1950s about an evolving cosmos based on radiosources (see chapter III), Hoyle & Burbidge (1966) pointed out that in fact their interlocutors had jumped the gun, as it were, and that their own goals had been modest, balanced, writing:

|

"While one can certainly express a personal

preference for this latter form of argument. it

is overstating the case to claim support from it

for one cosmology or another. It appears to us

that all these discussions are predicated on the

cosmological interpretation of the red-shifts of

the quasi-stellar objects, in the sense that

this interpretation is taken as axiomatic.

Conclusions following from it are accepted,

essentially whatever they may be, because a

non-cosmological interpretation [non-BB] is

taken to be out of the question. In fact,

the issue is an open one. The difficulties

of the problem, both observational and

theoretical, lie in deciding between the

cosmological and the 'local' interpretation, not

in seeing the implications of either one of them

by itself. Throughout our work on this subject,

we have been concerned to cover both sides of

the problem, rather than to concentrate on one

half. By doing so we have been able to place

limitations on the kind of model required in the

cosmological case, as well as in the local

case."

—Hoyle

& Burbidge (1966). Nature 212, 1334 [emphasis

added].

|

So below, we begin to discuss the data which show that in fact there are other causal factors which effect the observed redshifts of various kinds of galaxies and galactic objects which do not conform to the simple Hubble relation. Specific types of galaxies which do not neatly conform to the expected redshifts of the 'standard candles' even if they are apparently in comparable distances. Some of these extragalactic sources include quasars (QSOs), BL Lacertae objects (BL Lac), Seyfert galaxies, blue stellar x-ray objects, ultra-luminous infrared galaxies (ULIRGs), and other types of active galactic nuclei (AGNs) within the clusters and superclusters in which they occur. These associated objects with different redshifts indicate that some component(s) of z may not be Hubble-distance related. Some of the first phenomena we would expect to notice then, starting with canonical Hubble relation data, are

- (0) Early canonical redshifts

in the Hubble distance-redshift relation.

- (i) Unusual

scatters in the redshift-distance relationships of large

aggregates of galaxies and galactic objects.

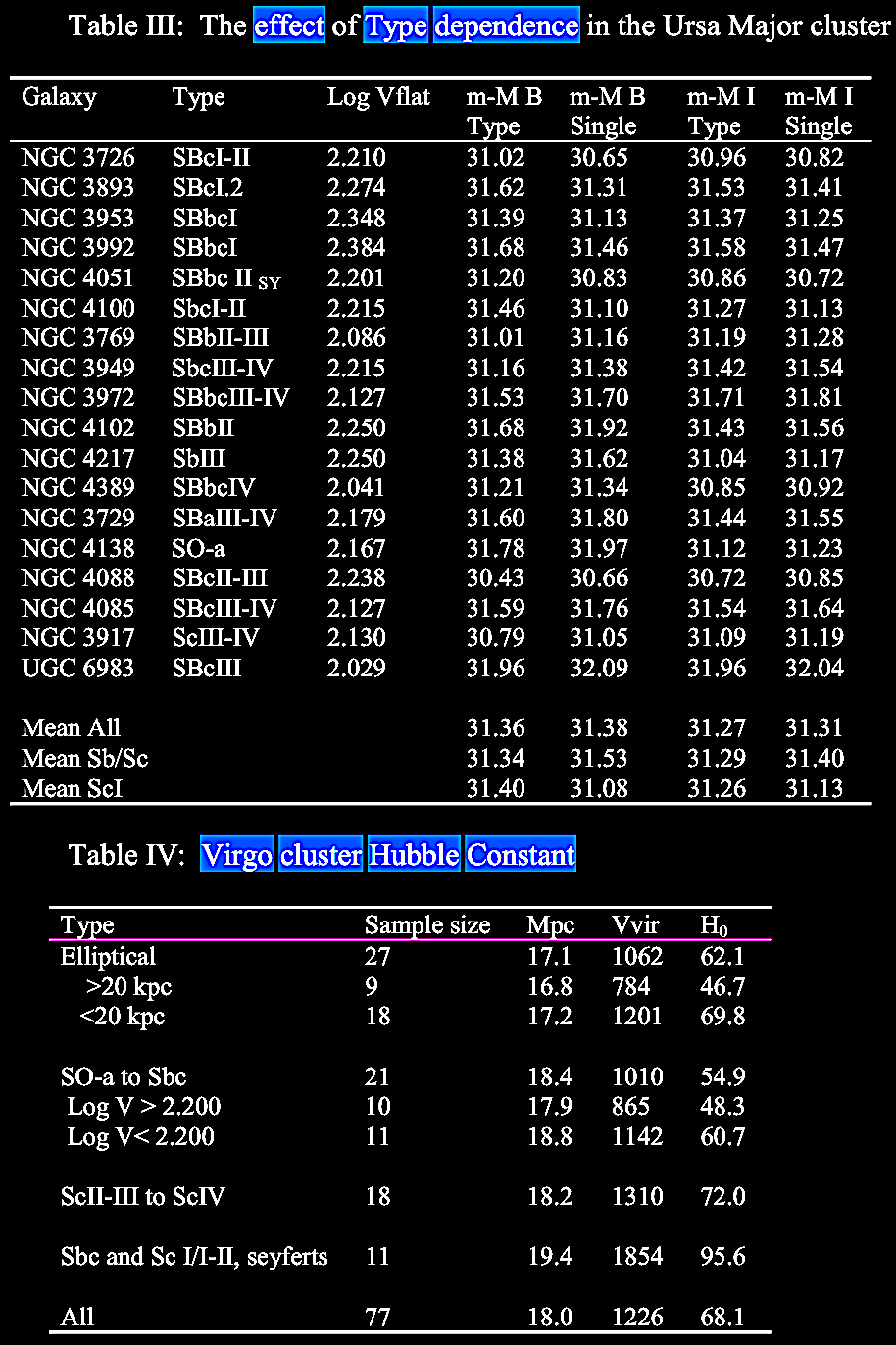

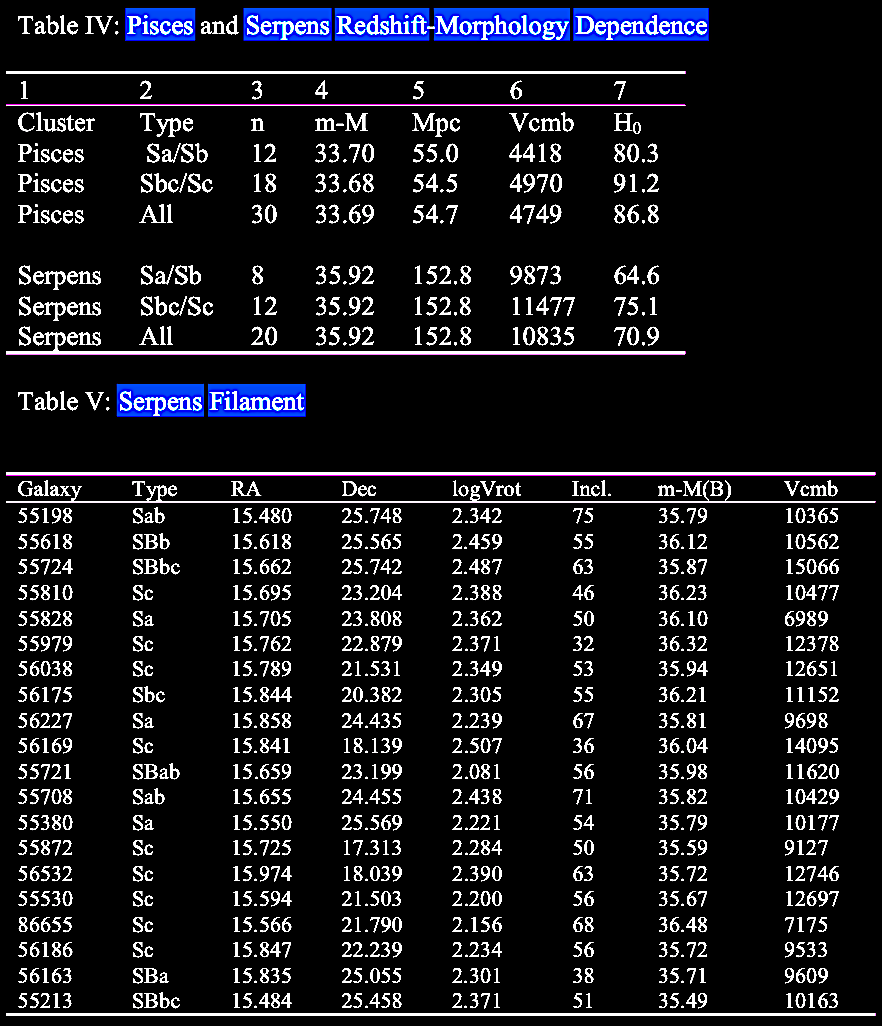

- (ii) Excess

redshifts dependent on galaxy morphologies.

- (iii)

Unexpected divergent redshift associations and apparent

ejection phenomena.

- (iv) Unusual

redshift periodicities which won't go away.

(0) Early canonical redshifts in the Hubble distance-redshift relationship:

Hubble relation (Hubble, 1929; from Hoyle et al. 2000). |

|

Hubble relation (Tolman, 1934; from Hoyle et al. 2000).

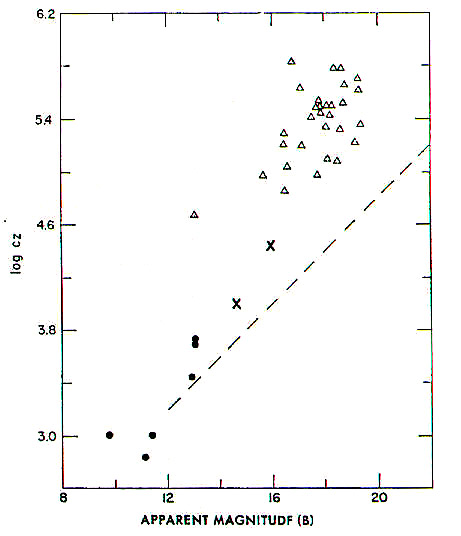

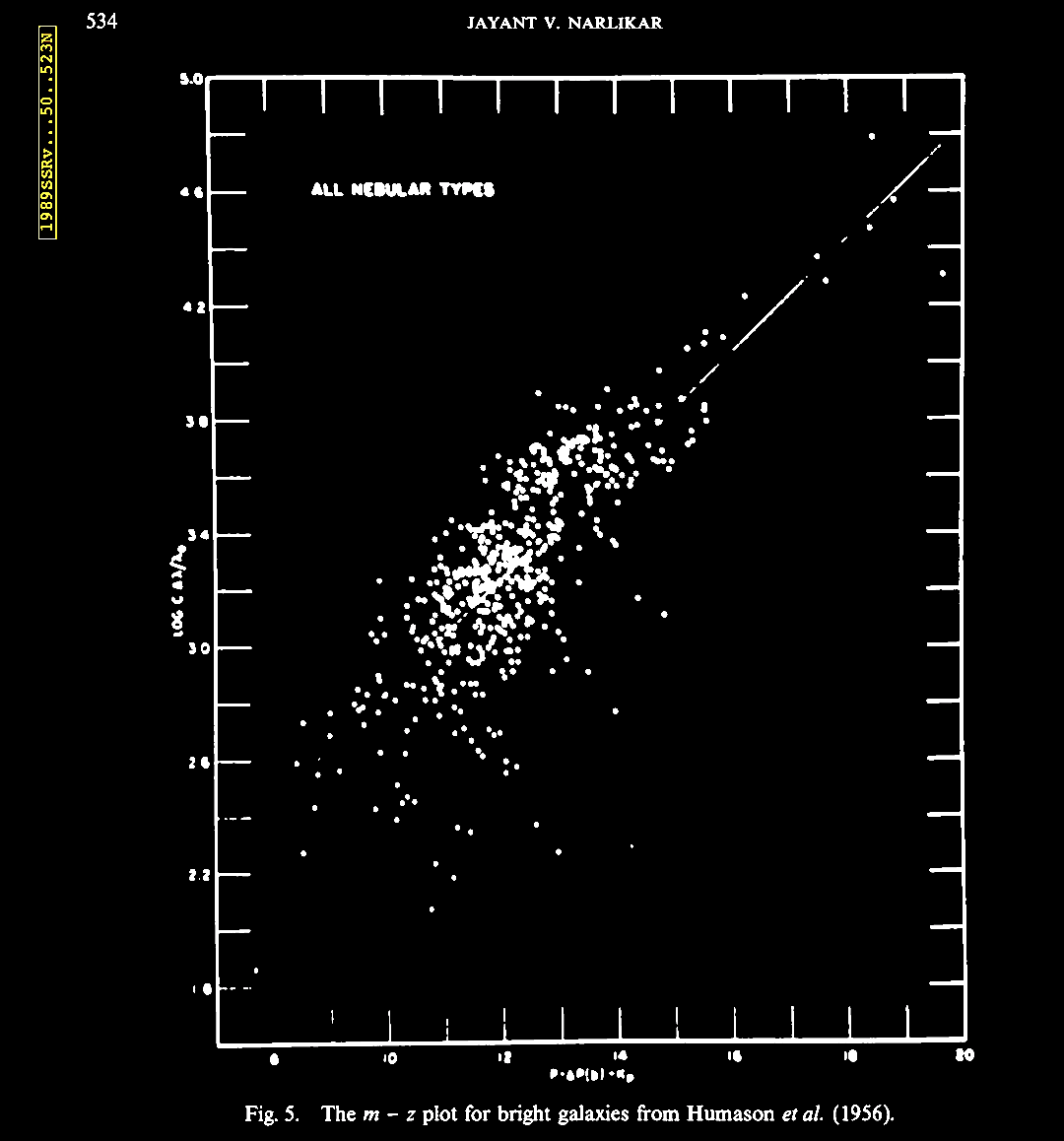

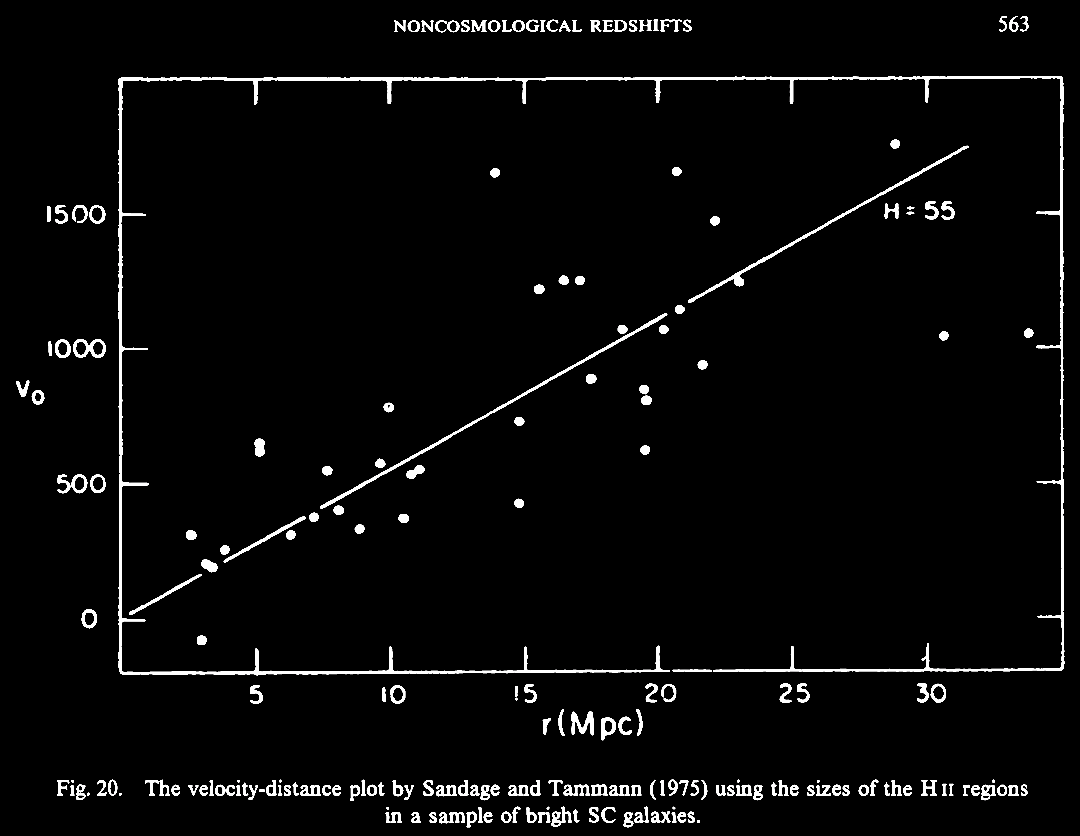

Some early (but not-understood) observations of this non-canonical or unexpected redshift scatter phenomena were compiled in the study of Lang et al. 1975 by plotting of galactic redshifts taken from the de Vaucouleurs, G. & de Vaucouleurs, A. 1964. Bright Galaxy Catalogue (Austin, TX: University of Texas Press; and since updated to a 3rd edition, 1994: https://heasarc.gsfc.nasa.gov/W3Browse/all/rc3.html). Among the 'bright' galaxies since the early 1960s there emerged a scatter of even the standard 'bright galaxies' in the de Vaucouleurs Catalogue.

Galaxy Radial Velocity (z in km s–1) versus

Apparent Magnitude (m). The data for this plot is taken

from Lang et al. (1975), from the 'Reference Catalogue

of Bright Galaxies' (de Vaucouleurs et al. 1964).

There is a high resolution PostScript version of this plot,

and the specific plot was created with Cat's eye (http://tarantella.gsfc.nasa.gov/viewer/example/catseye_intro.html).

In standard,

canonical, HBBC-compliant terms the scatter of redshifts was

interpreted as the peculiar velocities of the galaxies in a

cluster superimposed on the Hubble relation. However, that

effect is expected to dampen out and vanish with distance in

a standard interpretation. It does not.

Compiled by Allan Sandage, Palomar Observatories: Dashed lines

are supposed to represent the effect of peculiar velocities of

1000 - 2000 km/s (cited in Arp, 1998).

Compiled by Halton Arp (1968, cited in 1998), Max Planck

Institute: Solid circles = nearby Seyfert galaxies (gen.

spiral with very bright, rapidly varying nuclei); 'x's =

compact Seyfert-like galaxies; open triangles = QSOs; dashed

line represents predicted Hubble relation.

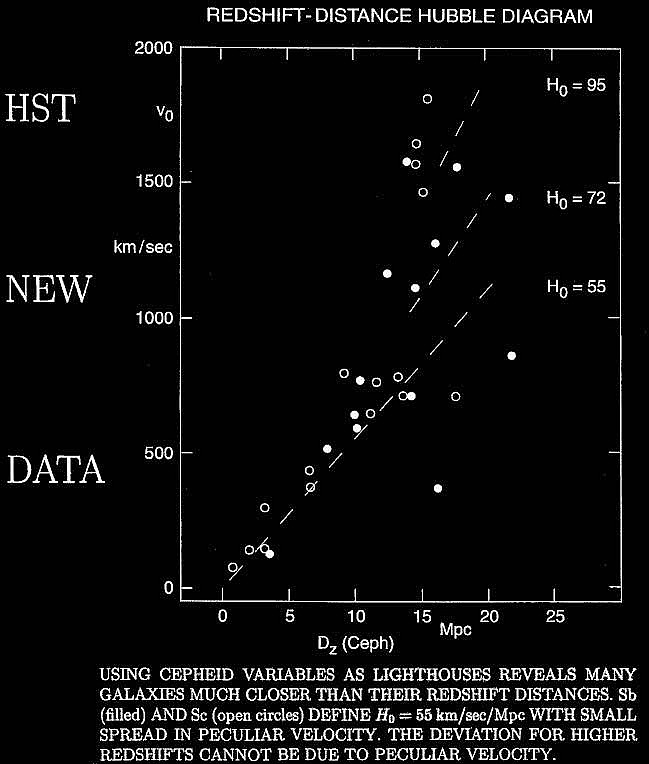

Redshift (v0) versus distance (Mpc): Ascending

Hubble relation according to Arp (1998).

By the early 2000s, the results were showing a scatter where the Cepheid distance ladder calculations showed galaxies nearer than indicated by their redshift (z) values. What was the meaning of these excess redshift values?

Based on data from the Hubble Space Telescope (www.haltonarp.org).

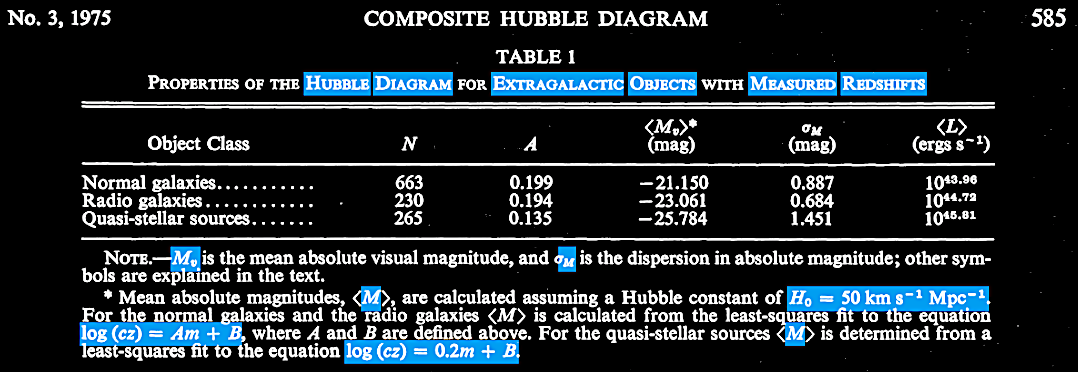

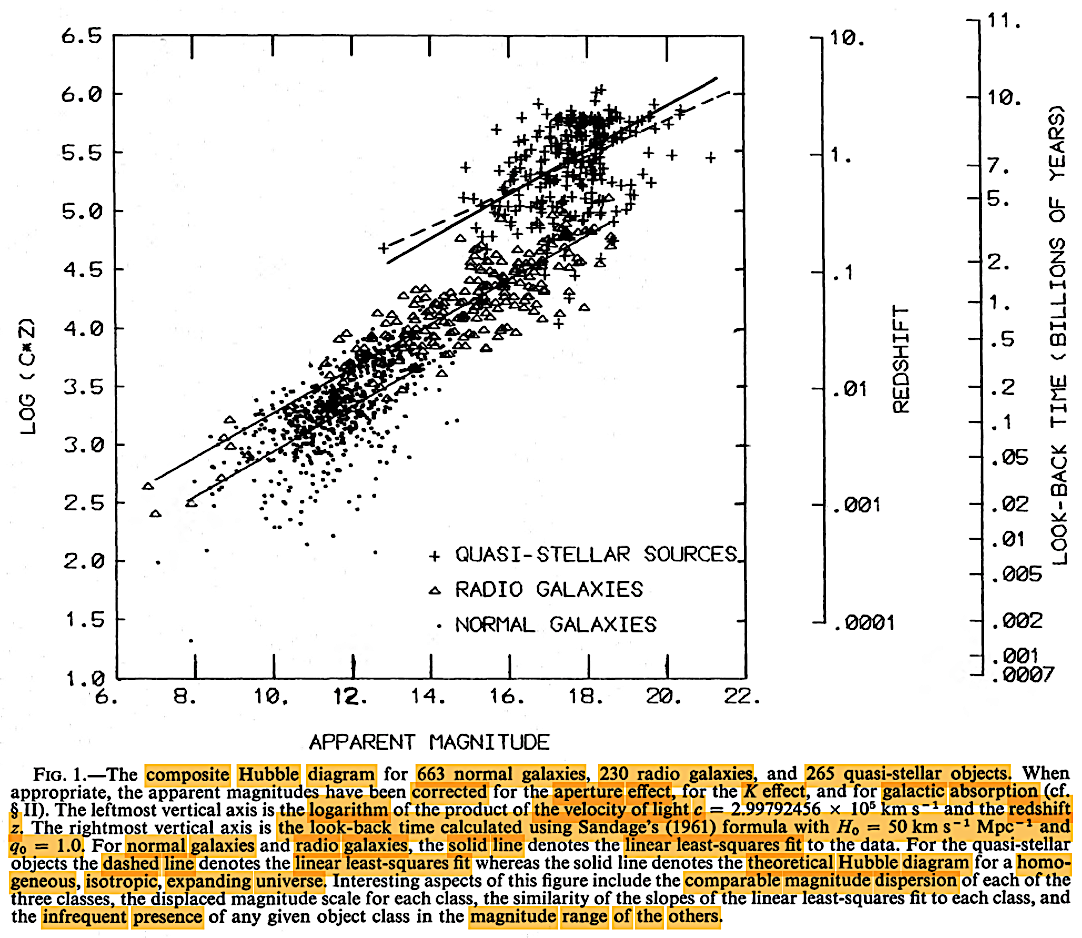

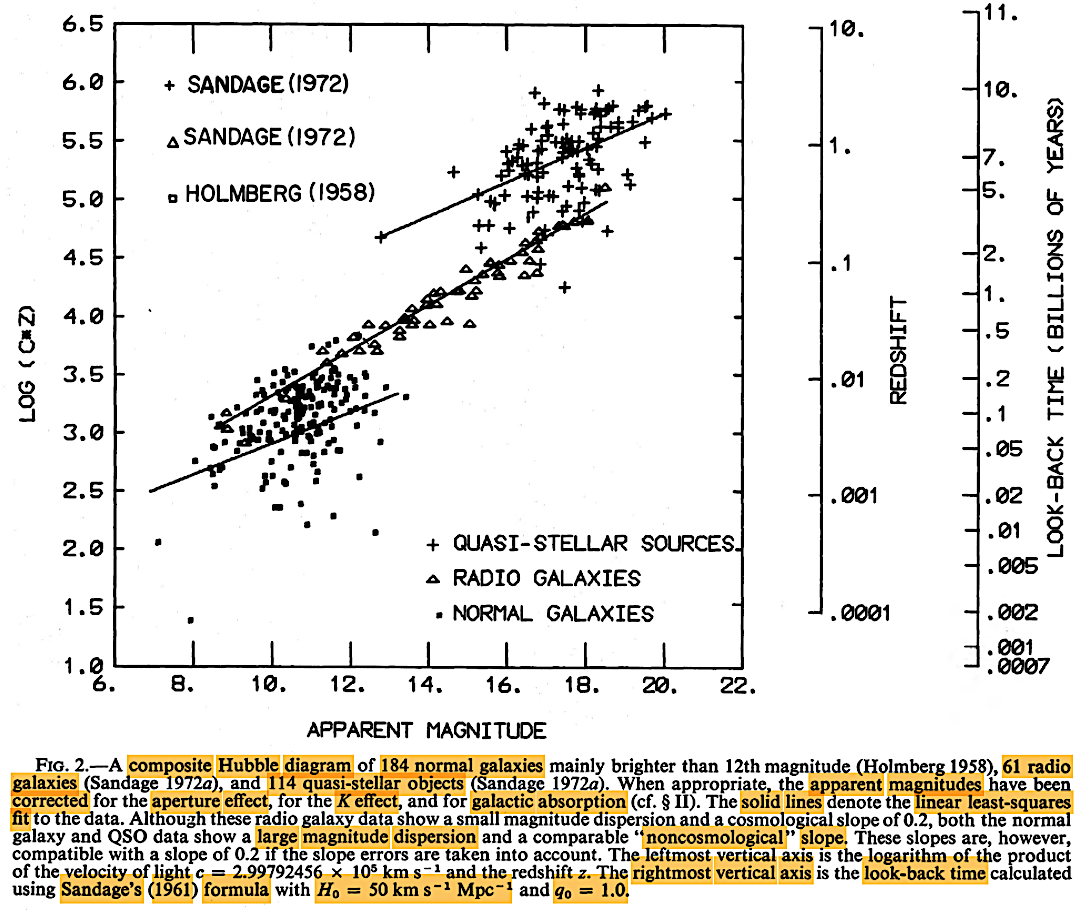

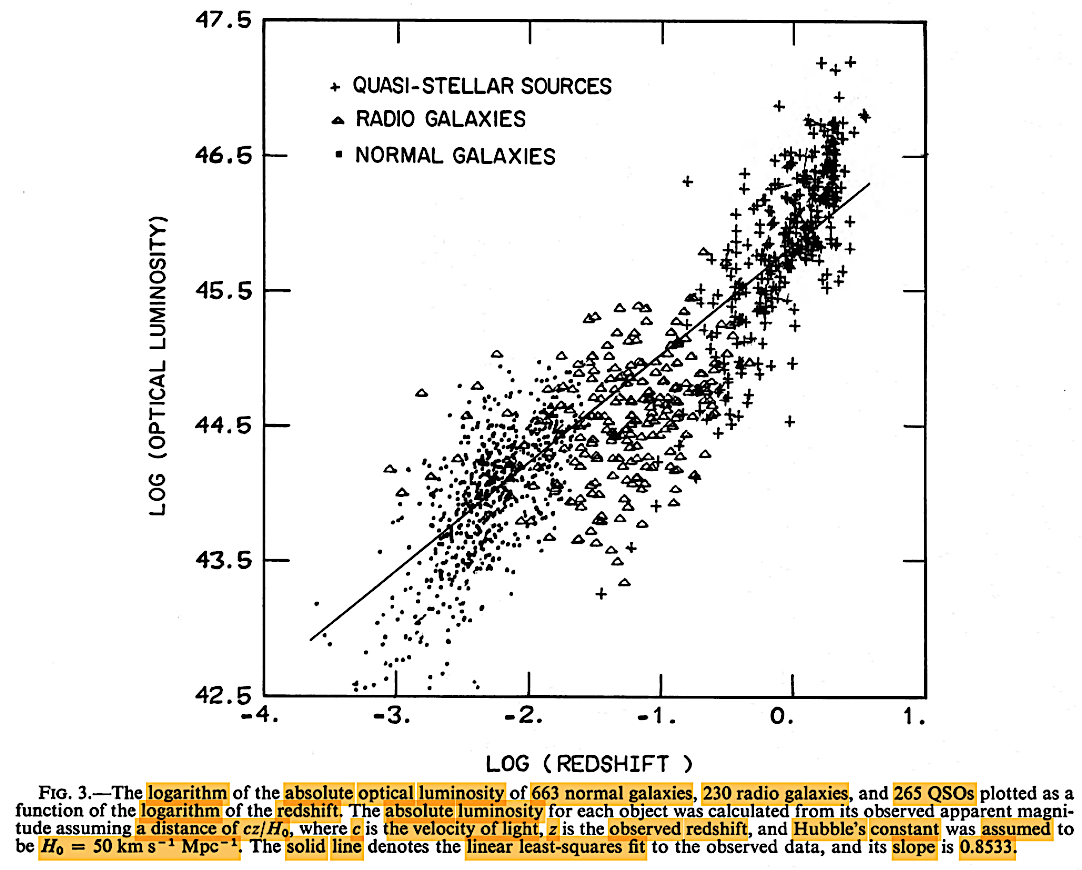

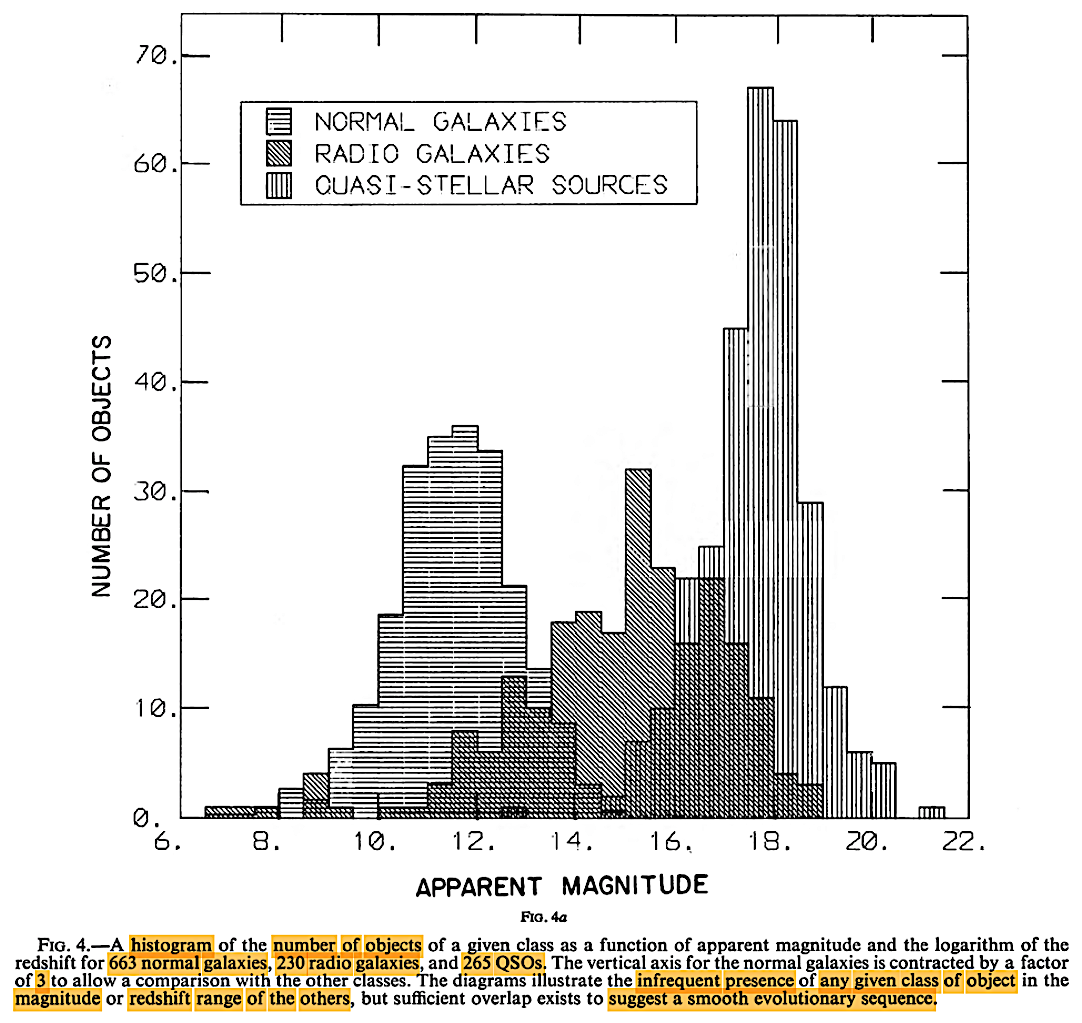

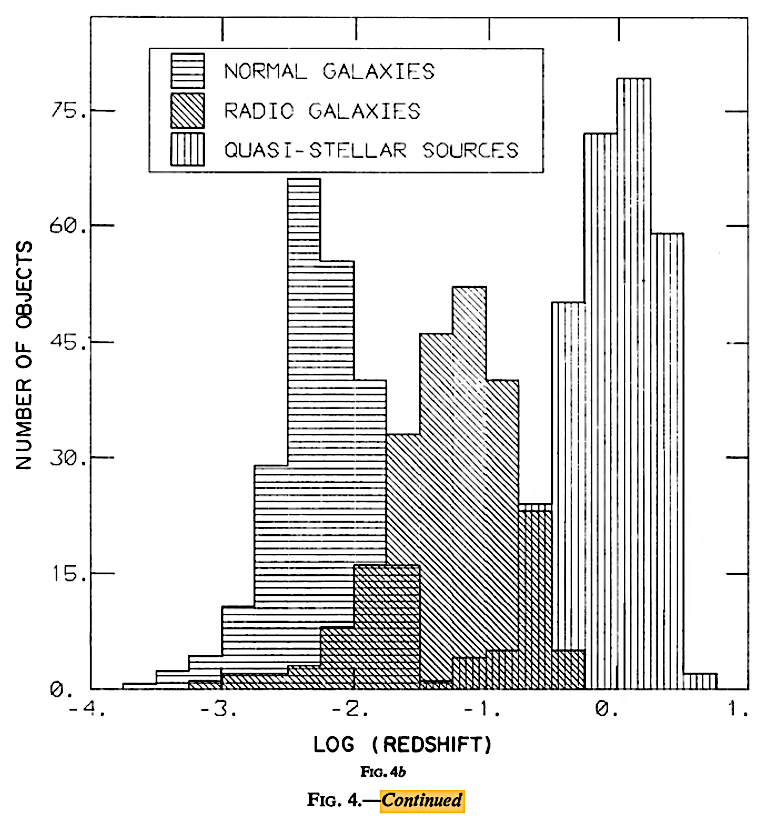

About a decade after the HBBC-CSSC controversy over QSOs, near the end of 1975, Lang, K. R. et al. published, The composite Hubble diagram. ApJ 202 (3), 583-590. https://articles.adsabs.harvard.edu/cgi-bin/nph-iarticle_query?1975ApJ...202..583, and sought to settle the issue in favor of evolutionary or HBB cosmologies by their analyses of the redshift situation among known QSOs as the situation stood nearly 10 years after the CSSC-HBBC-related arguments above. While they found showed an evolutionary sequence, it was not so much about the rival HBBC-CSSC models, but about the possible rival cosmogonies of galaxy evolution, as we shall see.

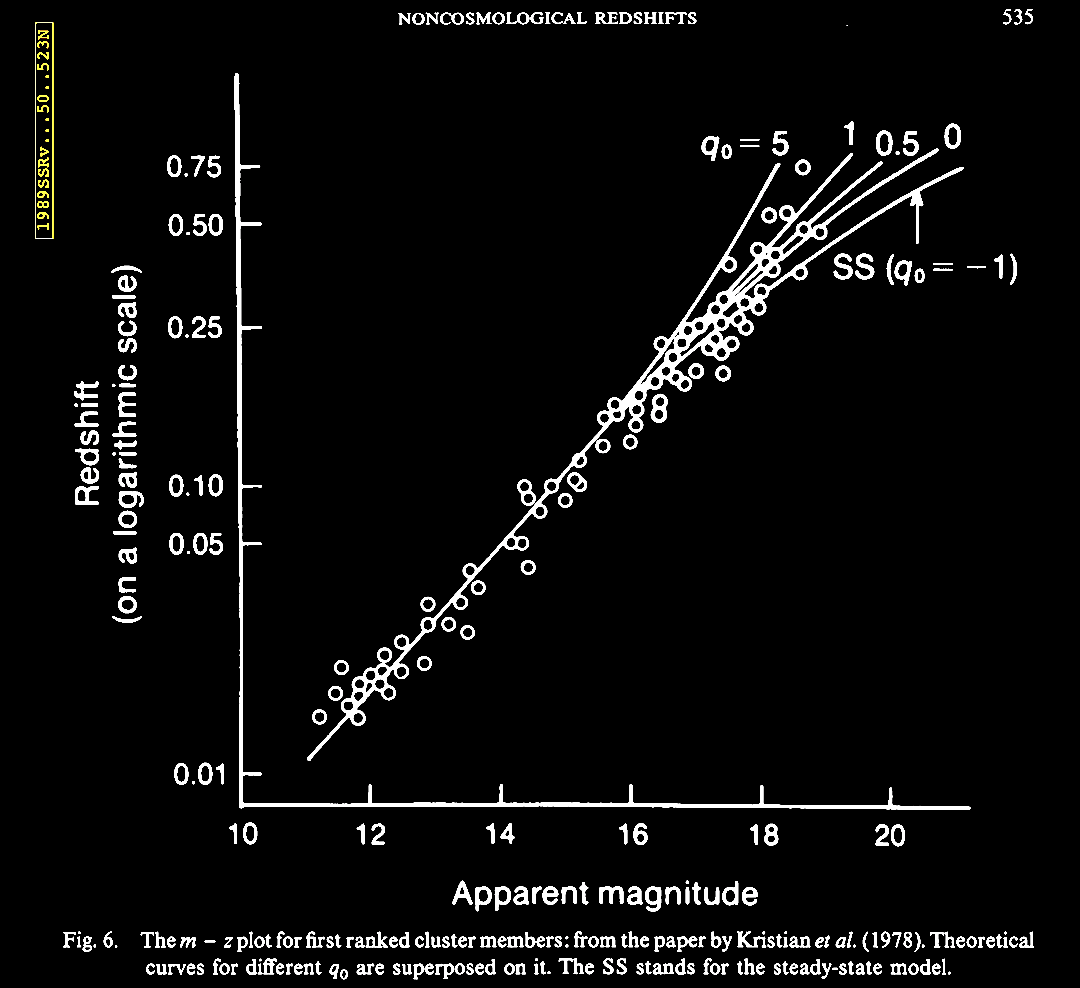

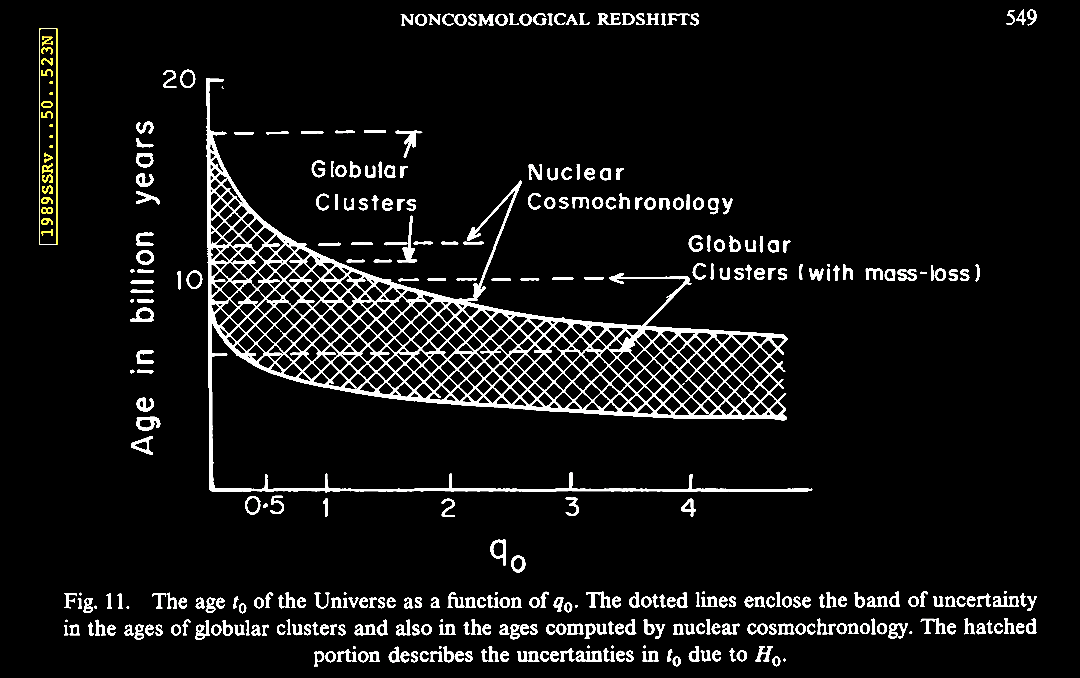

It is important to note that Lang et al. (1975) assumed the old Sandage and colleagues determined H0 = 50 km–1 Mpc–1 and a q0 = 1.0, when later H0 had jumped to nearly 70 km–1 Mpc–1 or higher (given the 'Hubble tension') and by 1998, the q0 parameter had switched sign to q0 = ~ –1, as discussed in chapter III and above, regarding the so-called 'accelerating Universe' or 'dark energy' discoveries.

|

|

|

|

Lang et al. (1975).

Lang et al. (1975) had indeed found an evolutionary sequence, but with the actual distances of the quasars not yet well-established, it was illusory as support for the HBBC, and as mentioned, it actually suggested something quite revolutionary as far as galactic cosmogony and evolution is concerned.

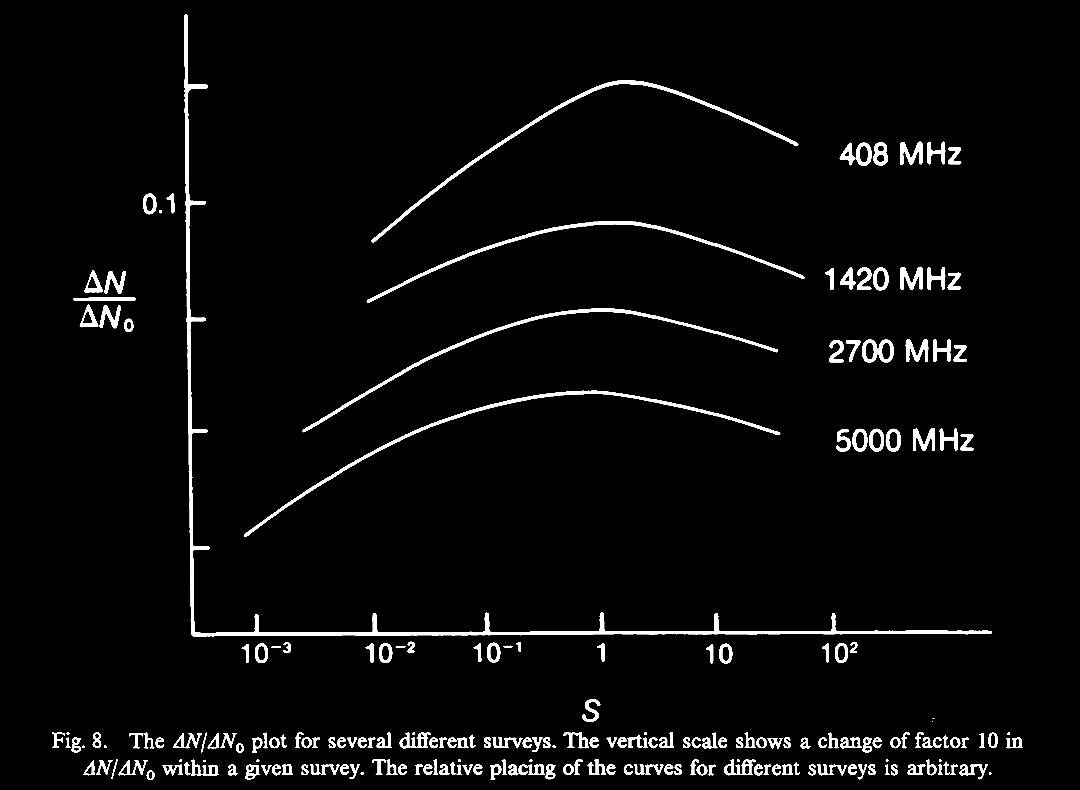

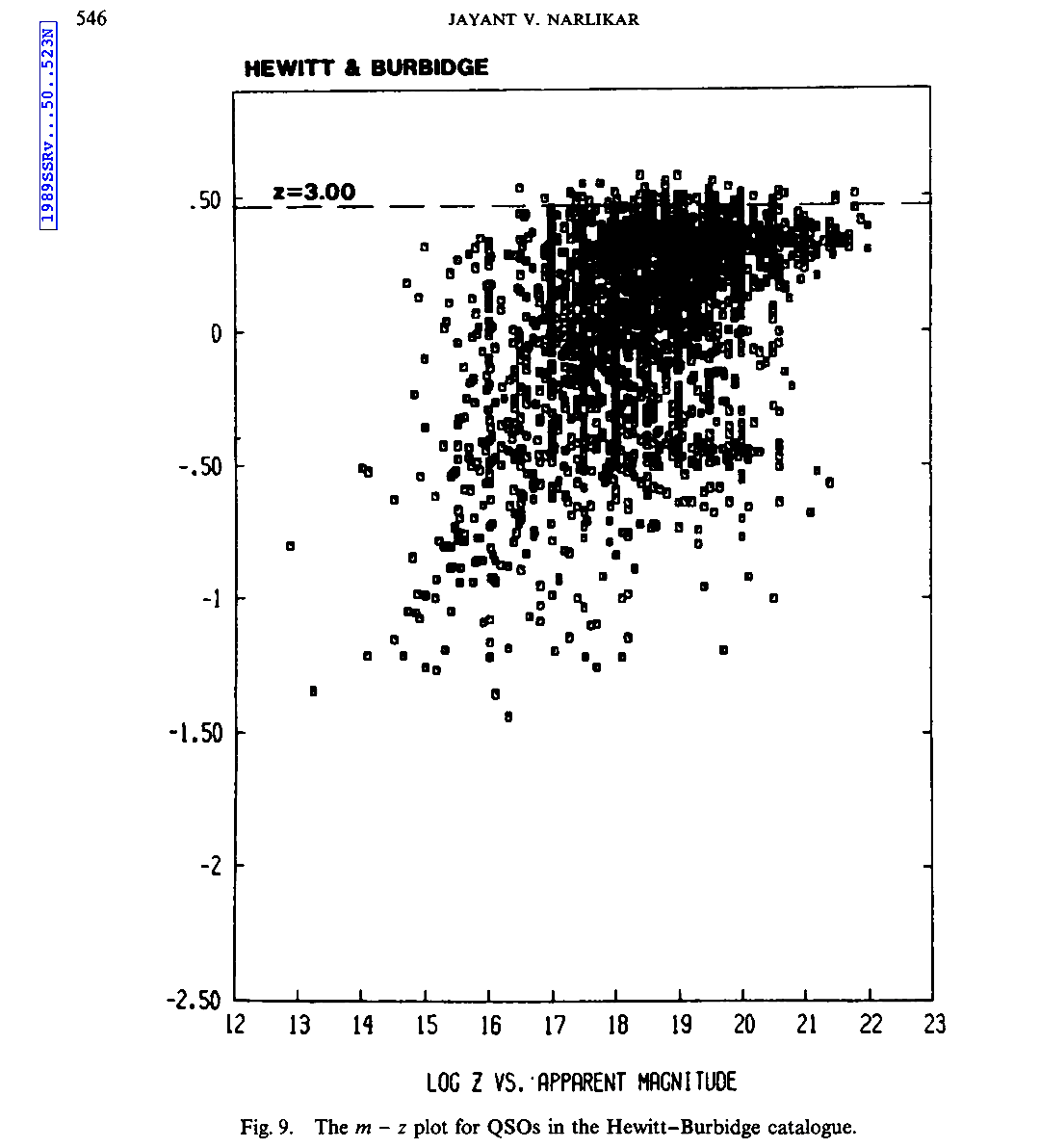

We turn to summaries of these emerging data showing a QSO scatter of redshifts.

(http://chandra.harvard.edu/xray_sources/3c273/xray_opt.html).

Scatters in

redshifts appear not only in linear size vs luminosity but

also in redshift vs spectral index (Condon, 1991).

Linear

Size versus Luminosity  For 1.4 Ghz radio sources brighter that 2 jansky, the distribution of linear size versus luminosity is a scatter diagram (Condon, 1991). |

Redshift

versus Spectral Index  The distribution of redshift versus spectral index at 1.4 GHz is also a scatter diagram (Condon, 1991). |

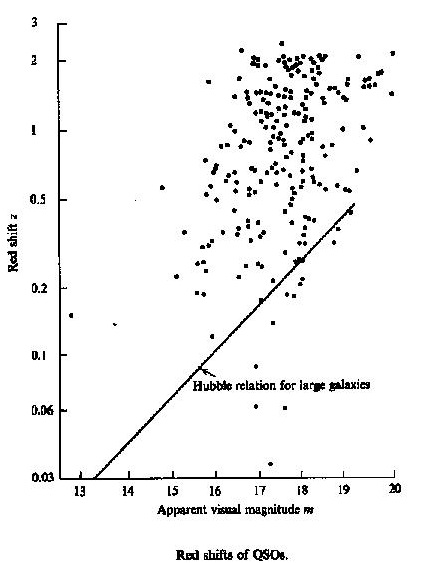

Greer (in a

1999 presentation at a science & religion conference in

Gallup, NM) presented these quasar (QSO) redshift scatters

in redshift (raw z as well as log z) vs

apparent magnitude (m) data from Hewett, P. C.,

Foltz, C. B., & Chaffee, F. H. 1995. The large bright

quasar survey [LBQS]. 6: Quasar catalogue and survey

parameters. AJ 109 (4), 1498. https://articles.adsabs.harvard.edu/full/1995AJ....109.1498H;

LBQS home: https://heasarc.gsfc.nasa.gov/W3Browse/all/lbqs.html).

Compiled & graphed by L. Greer (1999) from the LBQS data (Hewett et al. 1995). |

|

Excess QSO redshifts beyond

the Hubble relation for large galaxies (Joseph, 2010b).

With a much larger data set Hoyle, Burbidge, & Narlikar (2000) in their volume presenting the QSSC the following year, quasars were shown to have a scatter instead of a good correlation with the Hubble distance relation:

The empirical relation: m = 5 log (z) + H0 (km s–1 Mpc–1)|

|

Angular locations of the then-known 7315 QSOs projected on Milky Way Galactic coordinates (Hewitt & Burbidge, 1993; cit. in Hoyle et al. 2000). |

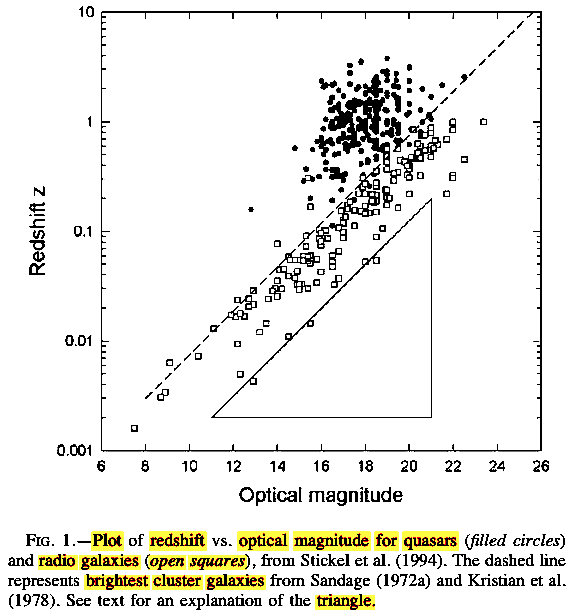

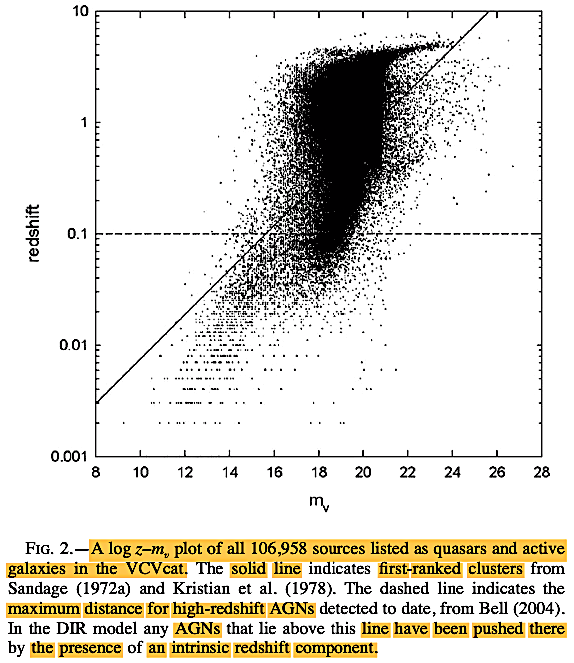

Further studies

confirmed an intrinsic excess of redshifts in certain AGNs,

such as QSOs and even radio galaxies. In pursuit of insights

from the Ambartsumian-Vorontsov-Vel'yaminov-Arp (AVVA)

cosmogony of ejection of higher redshift compact galactic

objects from lower redshift AGNs (see chapter IX),

Bell, M. B. 2007. Further evidence that the redshifts of AGN

galaxies may contain intrinsic components. arXiv release (v1

12 Apr 2007; v2 21 Aug 2007): https://arxiv.org/abs/0704.1631.

ApJ 667 (2), L129. https://doi.org/10.1086/522337,

referring to the DIR (declining intrinsic redshifts)

post-ejection evolving with increasing luminosity. According

to the DIR deductions from the Ambartsumian-Vorontsov-Vel'yaminov-Arp (AVVA)

cosmogony young AGNs or QSOs evolve into BL Lac objects,

Seyfert galaxies, and in the penultimate stage into radio

galaxies before losing the rest of their intrinsic redshift

and becoming quiescent mature galaxies. Because of low

redshift galaxies and high redshift compact sources, we can

now infer that the evolutionary pattern Lang et al.

espied in 1974 does not show the evolutionary BB cosmology,

but the stages of the Ambartsumian-Vorontsov-Vel'yaminov-Arp

(AVVA) cosmogony of galaxies (see chapter

IX), and a brief introduction below.

The triangle at the

lower right pf Figure 1 represents where the QSOs

would be if the intrinsic component were absent.

|

|

The intrinsic

redshifts of AGNs suggest that we should expect increased

departures from the ordinary H0 redshift

relation perhaps with the degree of the energetic activity of

AGNs.

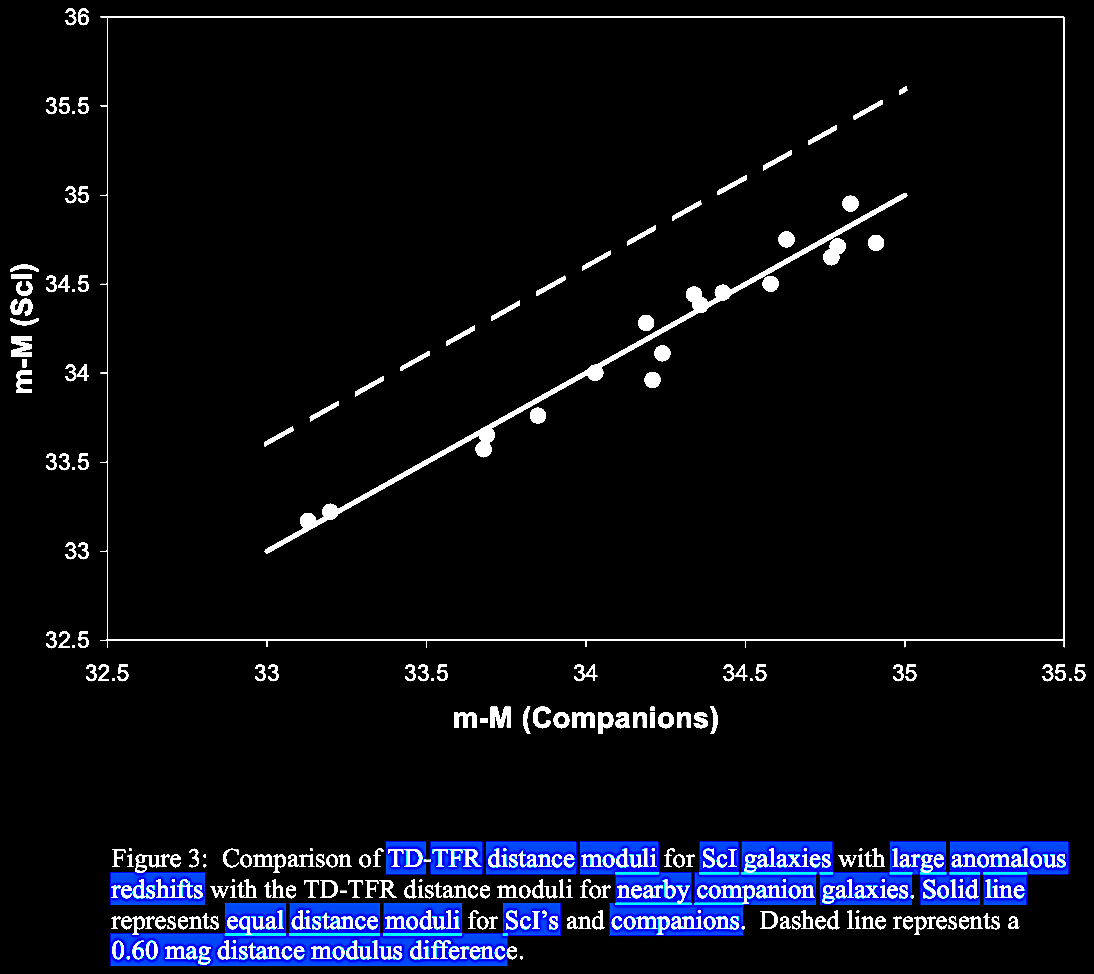

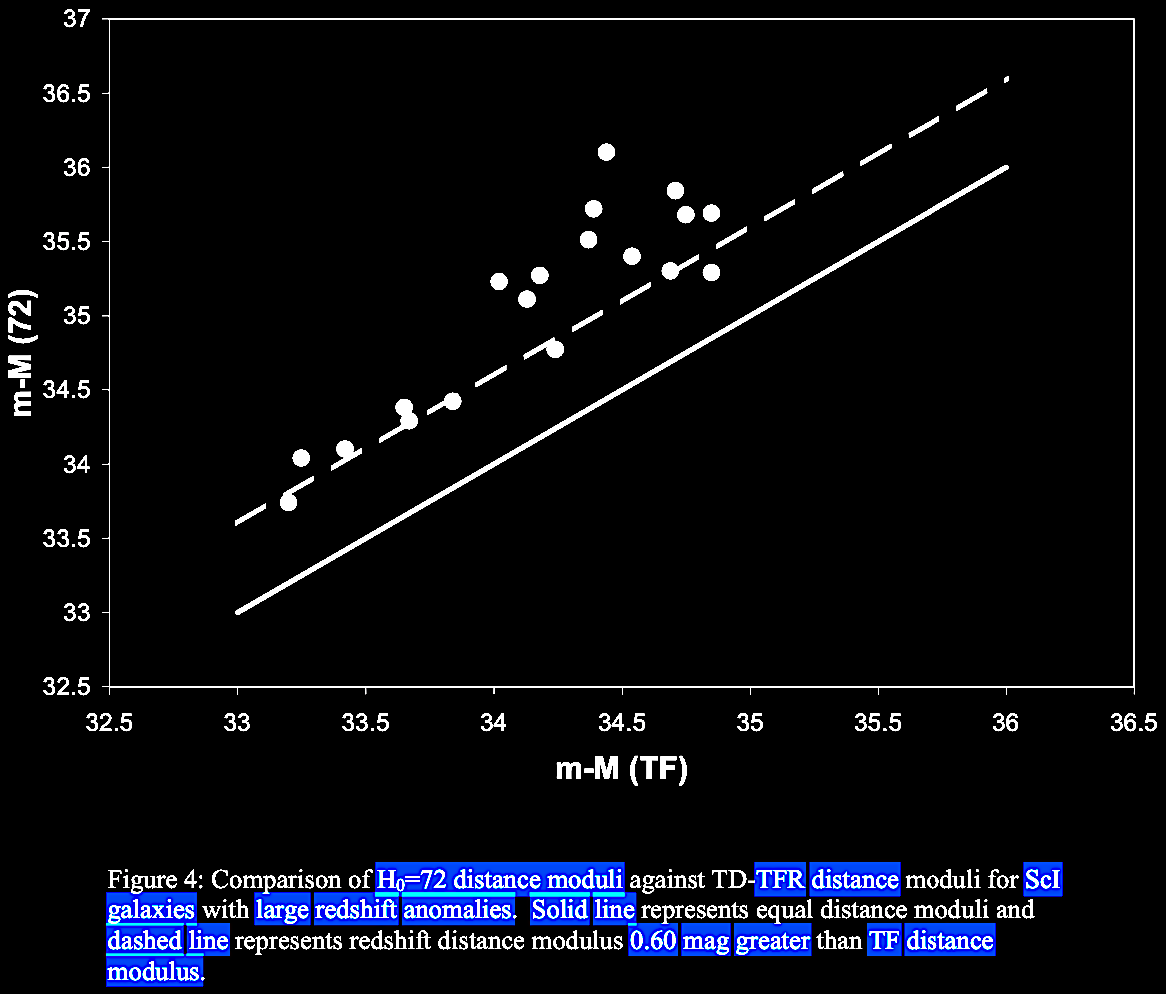

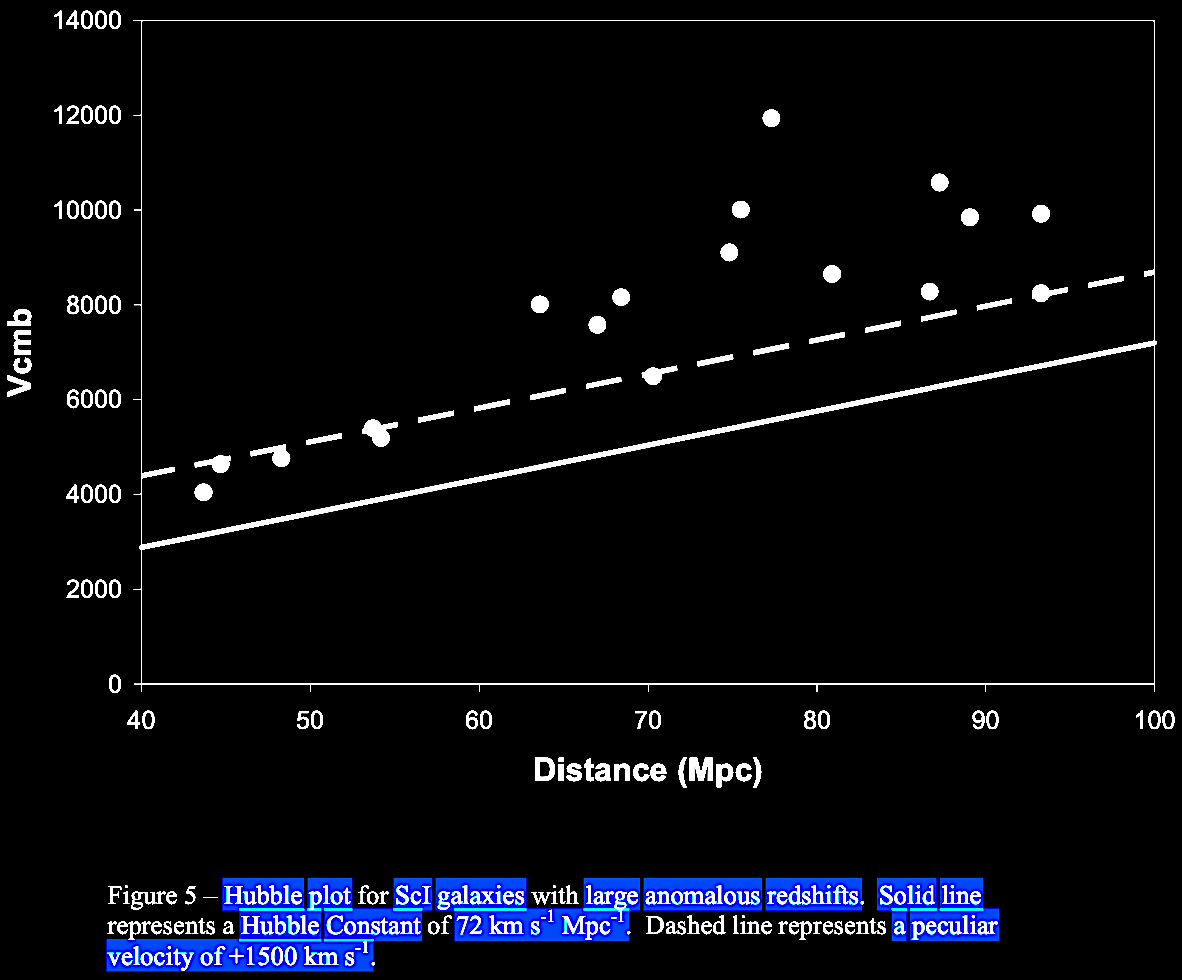

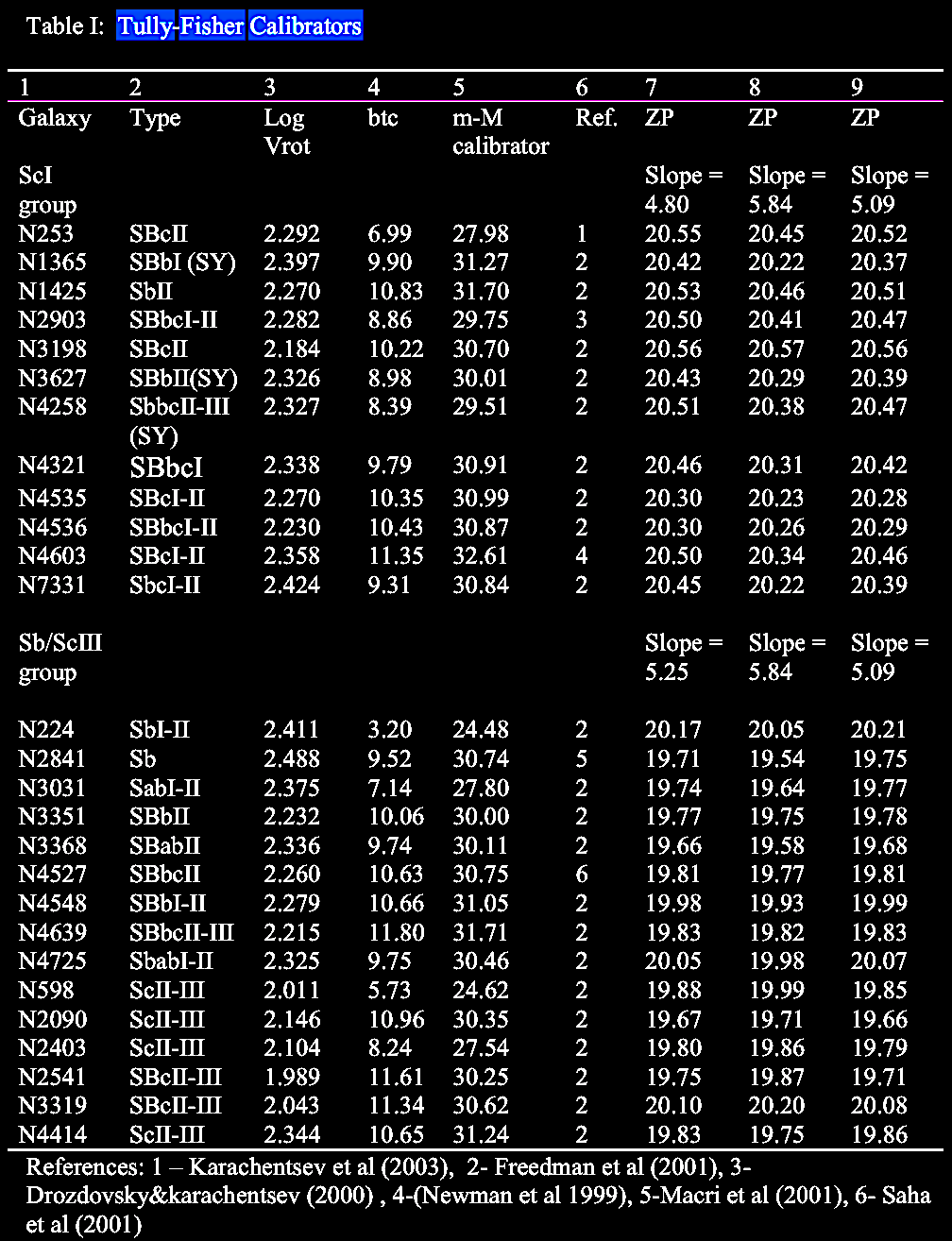

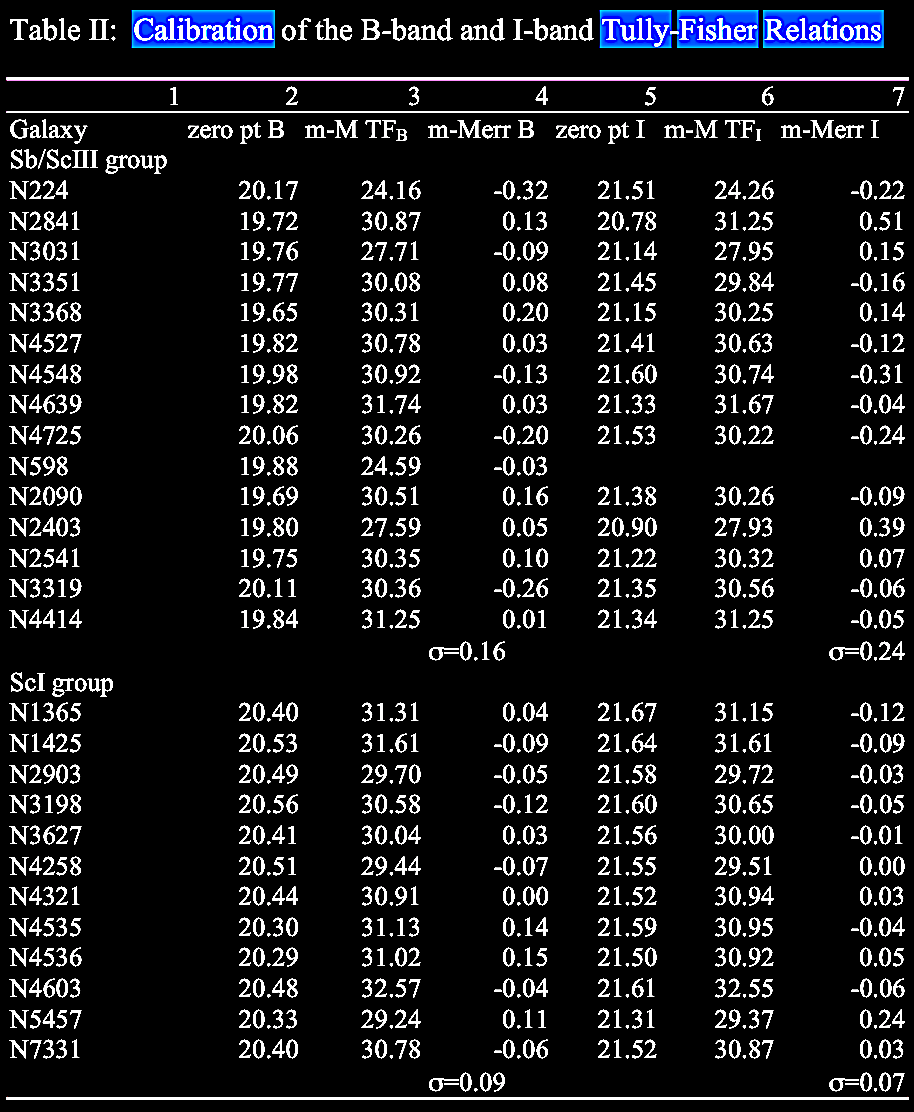

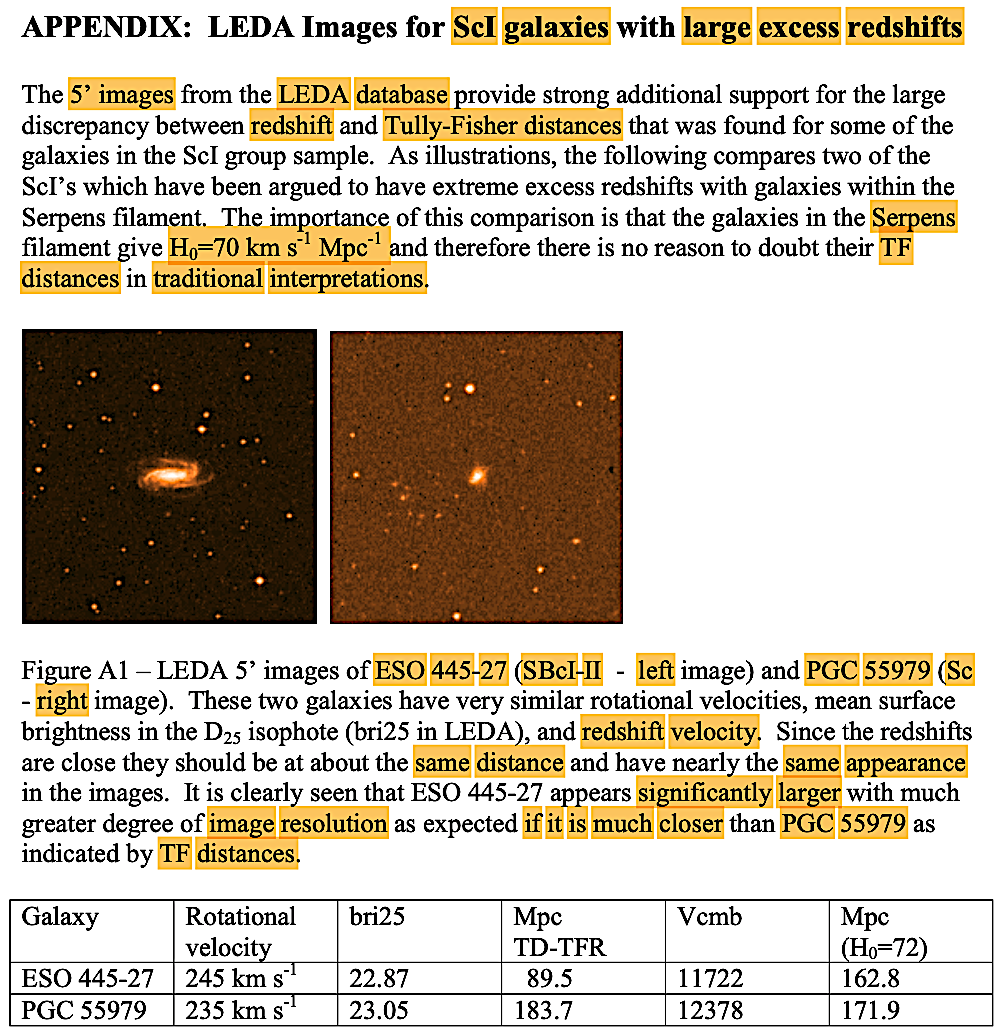

Although the QSOs and

other types of AGNs attracted more attention, some little

noticed papers showed evidence for intrinsic (non-canonical)

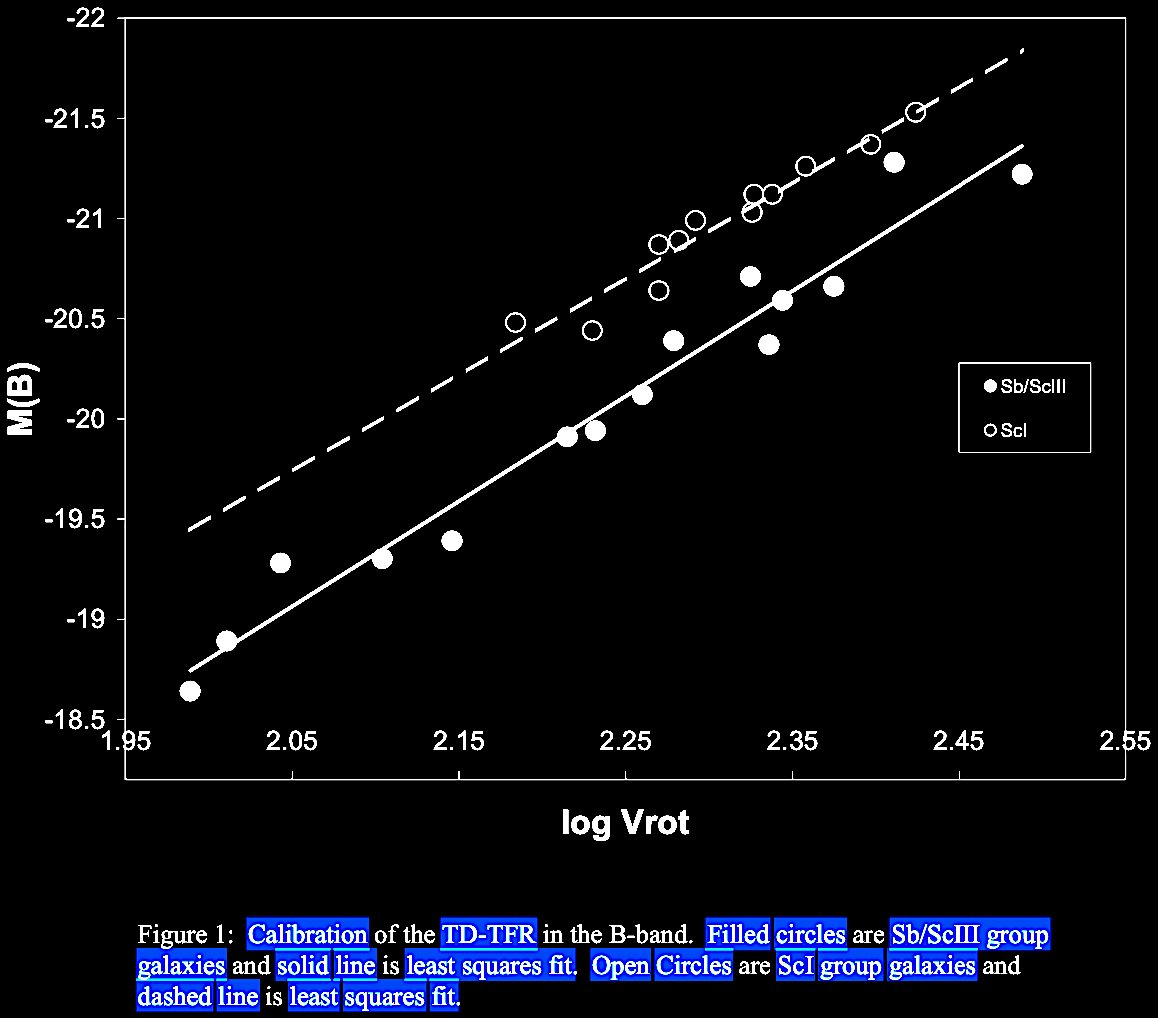

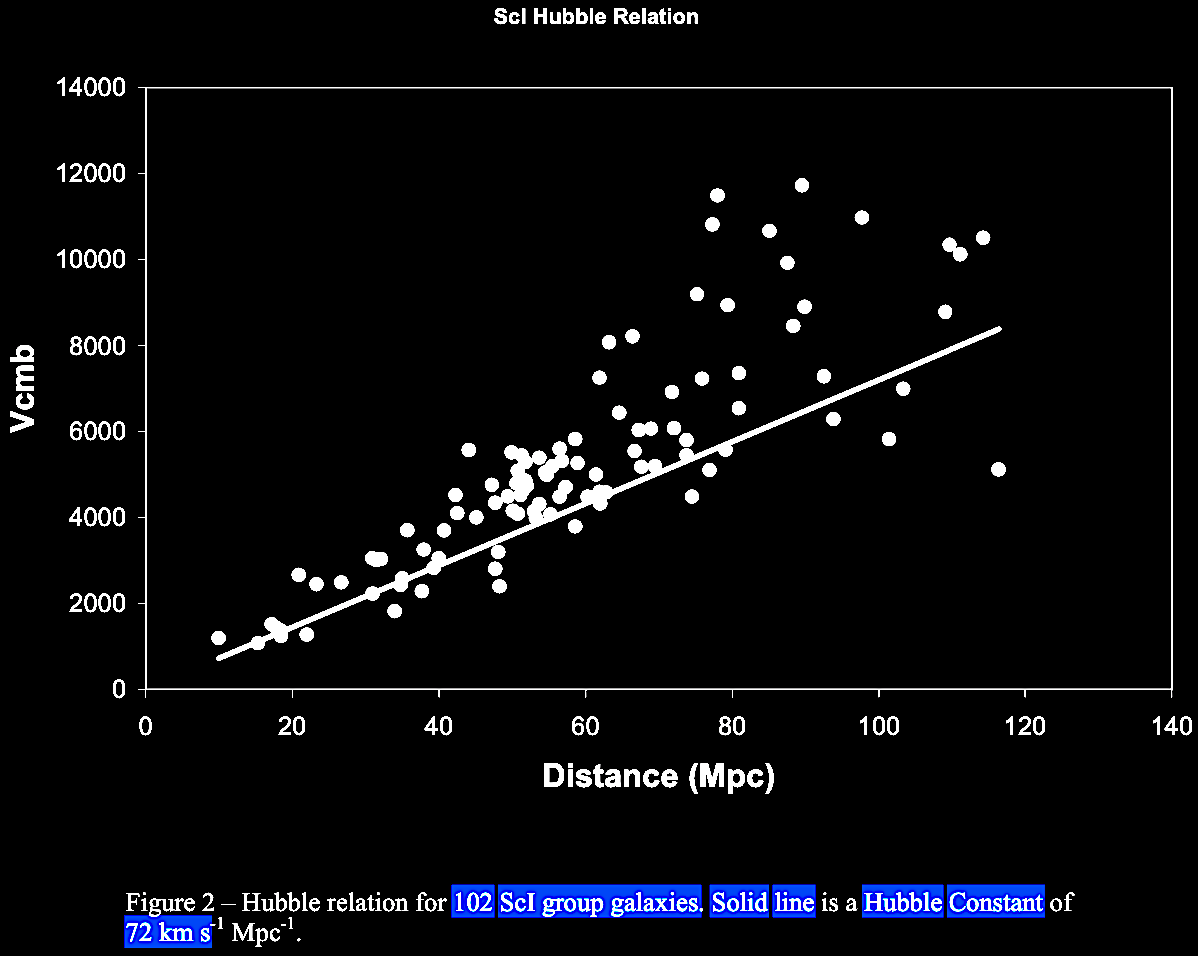

redshifts in regular spiral galaxies: Russell, D. G. arXiv: v1

19 Aug 2004; v2 26 Sep 2004: https://arxiv.org/abs/astro-ph/0408348); 2005. Evidence for intrinsic

redshifts in normal spiral galaxies. Astrophys Space Sci

298, 577. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10509-005-2317-x.

Russell summarized data showing that even ordinary spiral

galaxies have some excess redshift component, above the Hubble

constant redshift-distance relation expectations. In his 2004

arXiv manuscript, Russell had diagrams to show this, including

some intrinsic additional redshift seemingly dependent in part

on morphology, calibrated by the commonly-used Tully-Fisher

relation (link)

between mass / intrinsic luminosity (of spiral galaxies) vs.

asymptotic rotation velocity (expressed as emission line

width).

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

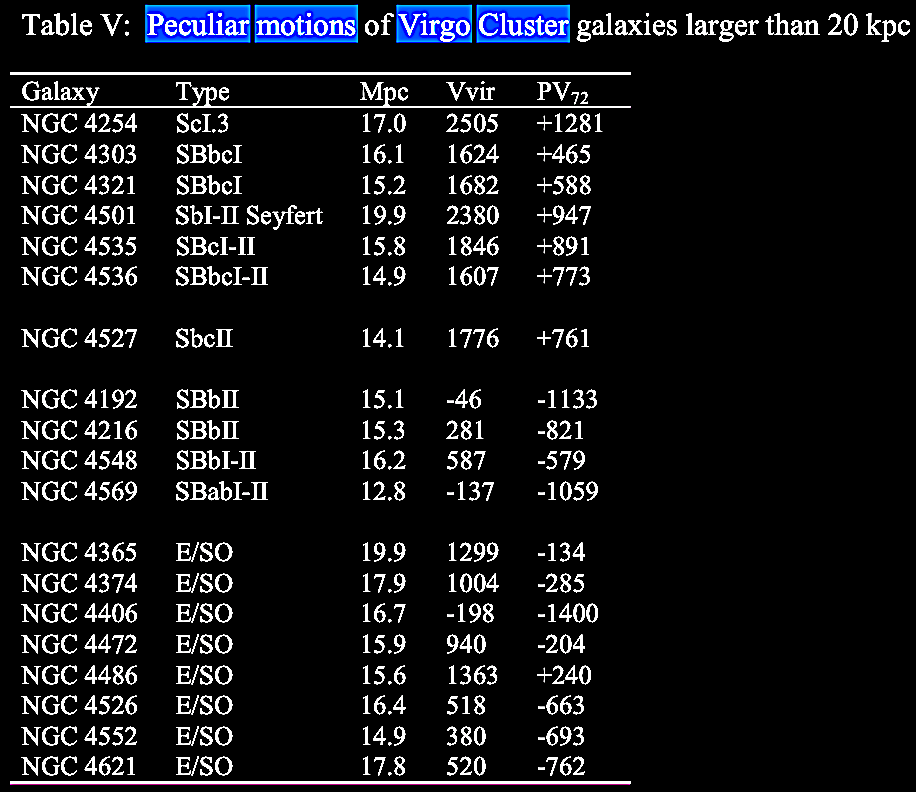

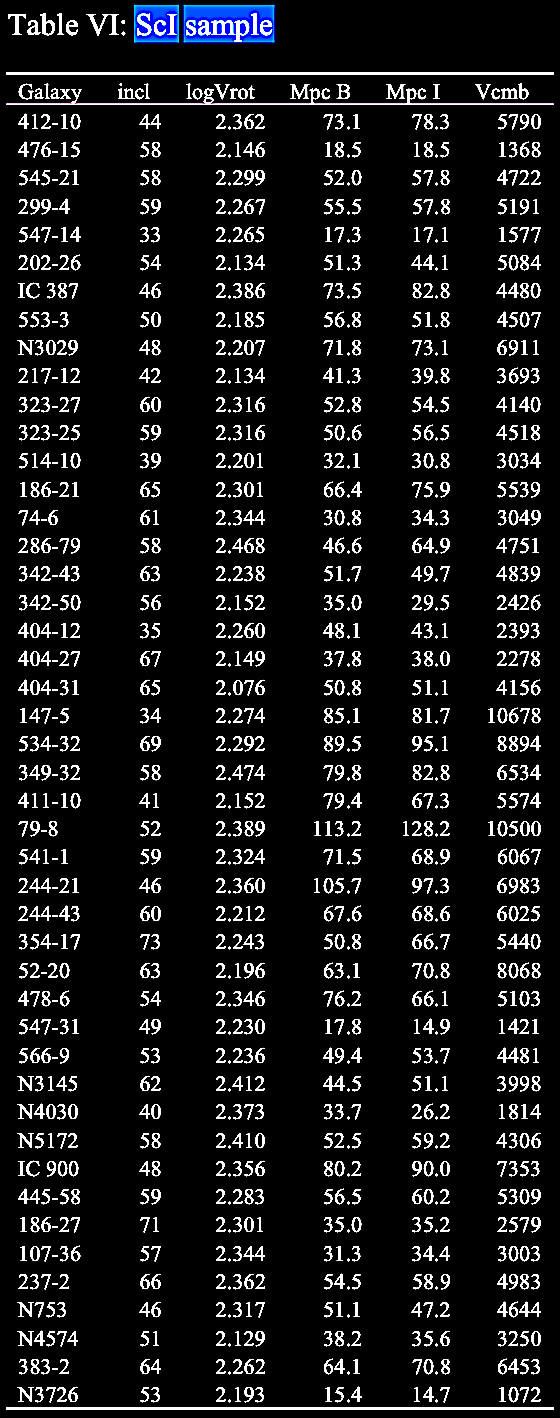

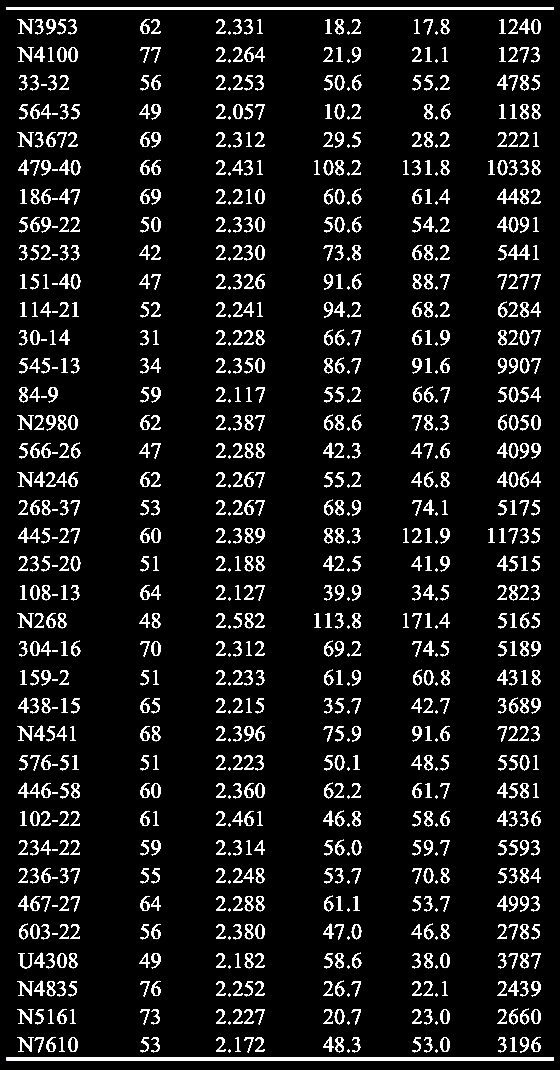

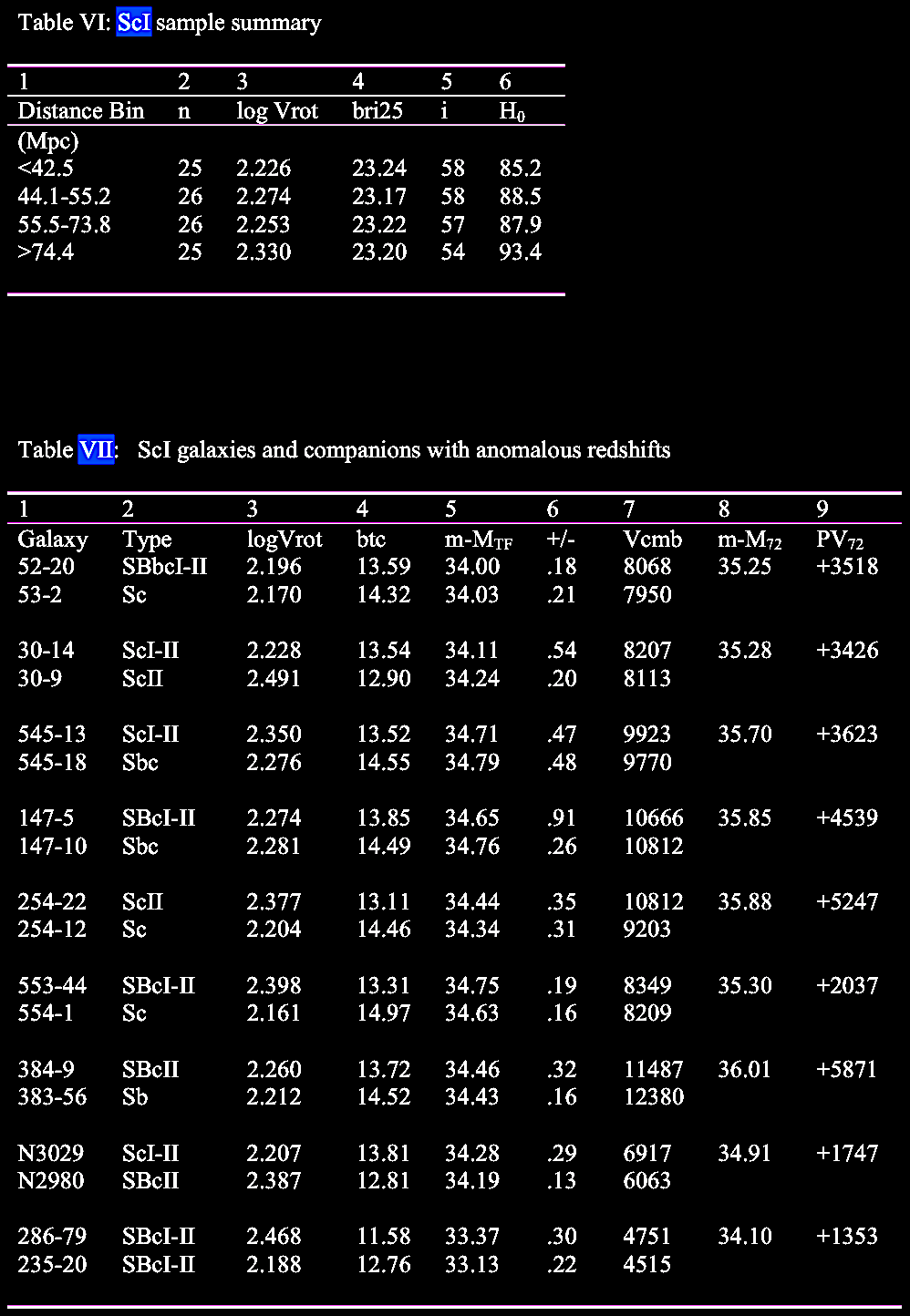

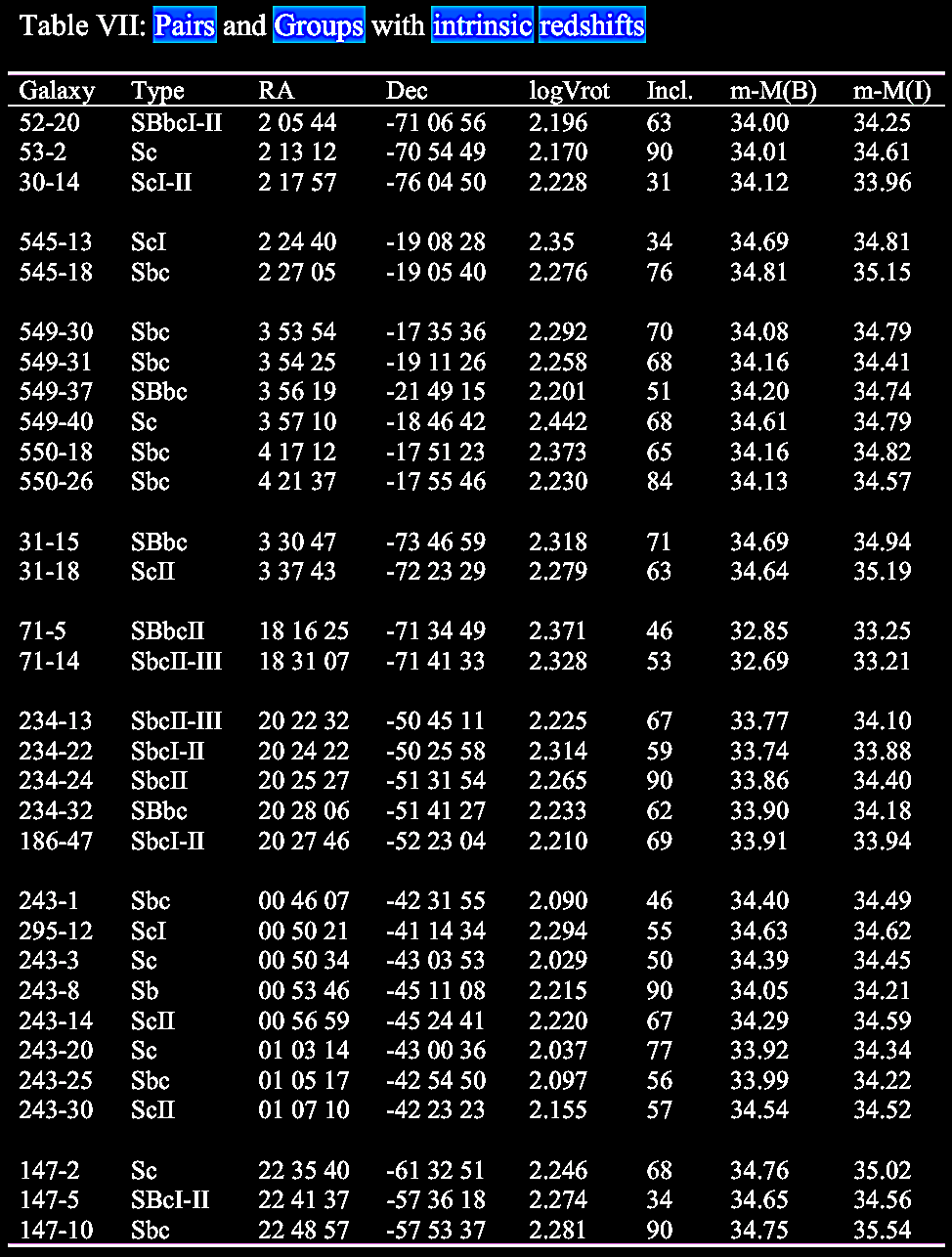

In Table

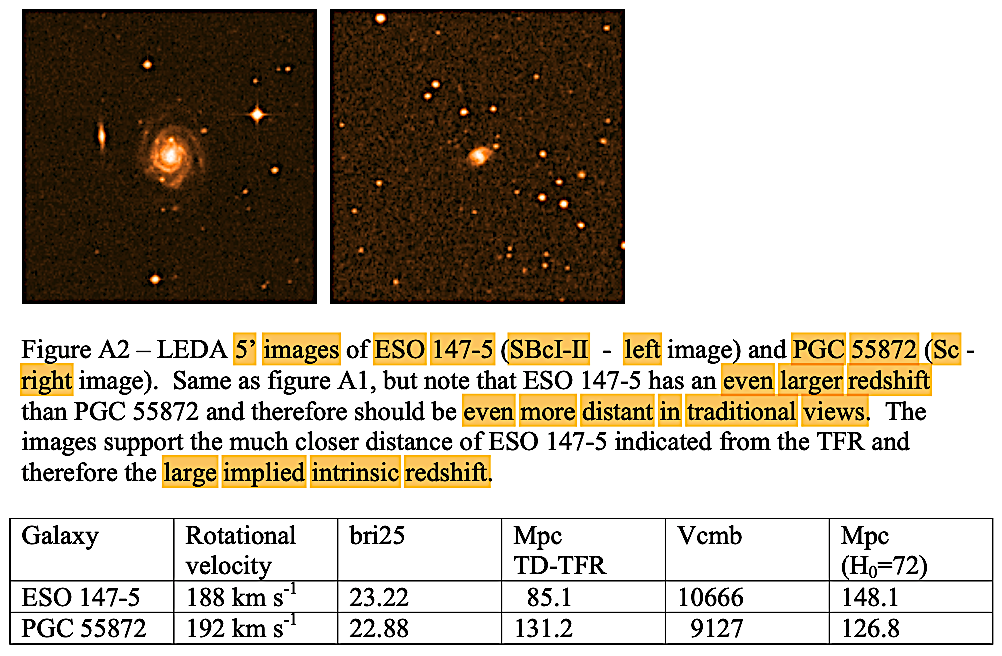

VI in the next two cells below, the barred spiral ScI

data are of especial interest since they include the

largest cohort of the barred spiral galaxies in the

study. |

|

Table VI:

ScI sample (cont.). |

|

|

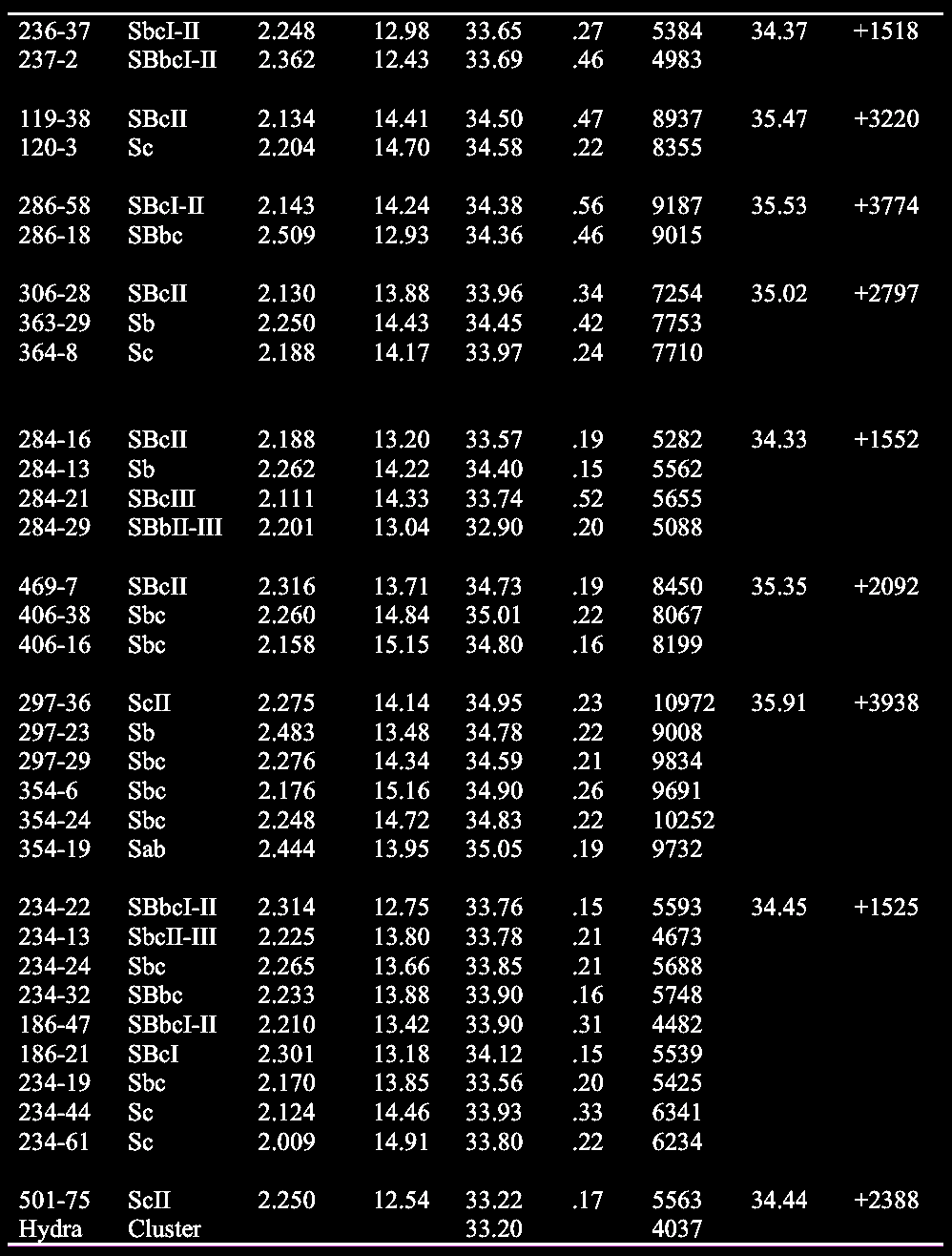

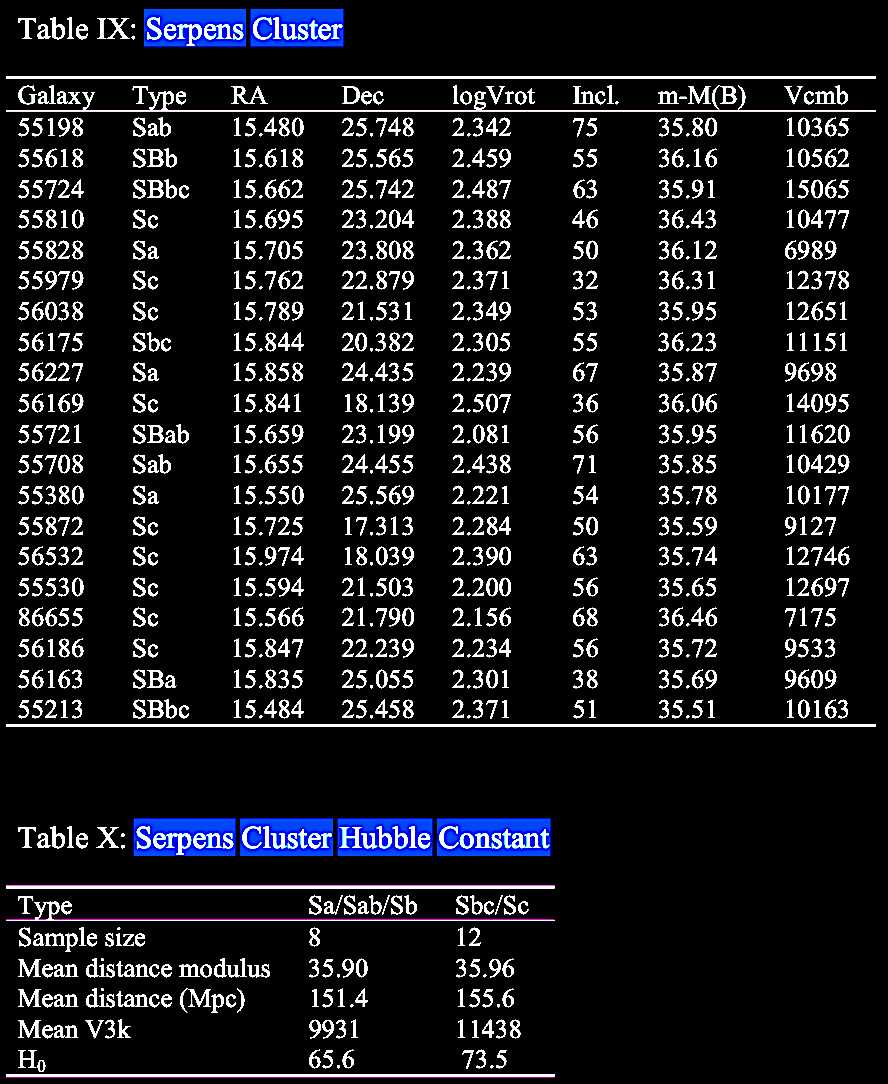

Table VIII. Excess redshifts of small groups (cont.).  Excess or intrinsic redshifts associated with small groups of galaxies. |

|

|

|

Next, we turn to

divergent redshift associations and the early hypothesis of

galactic ejection phenomena, which will be discussed in depth

in later chapters.

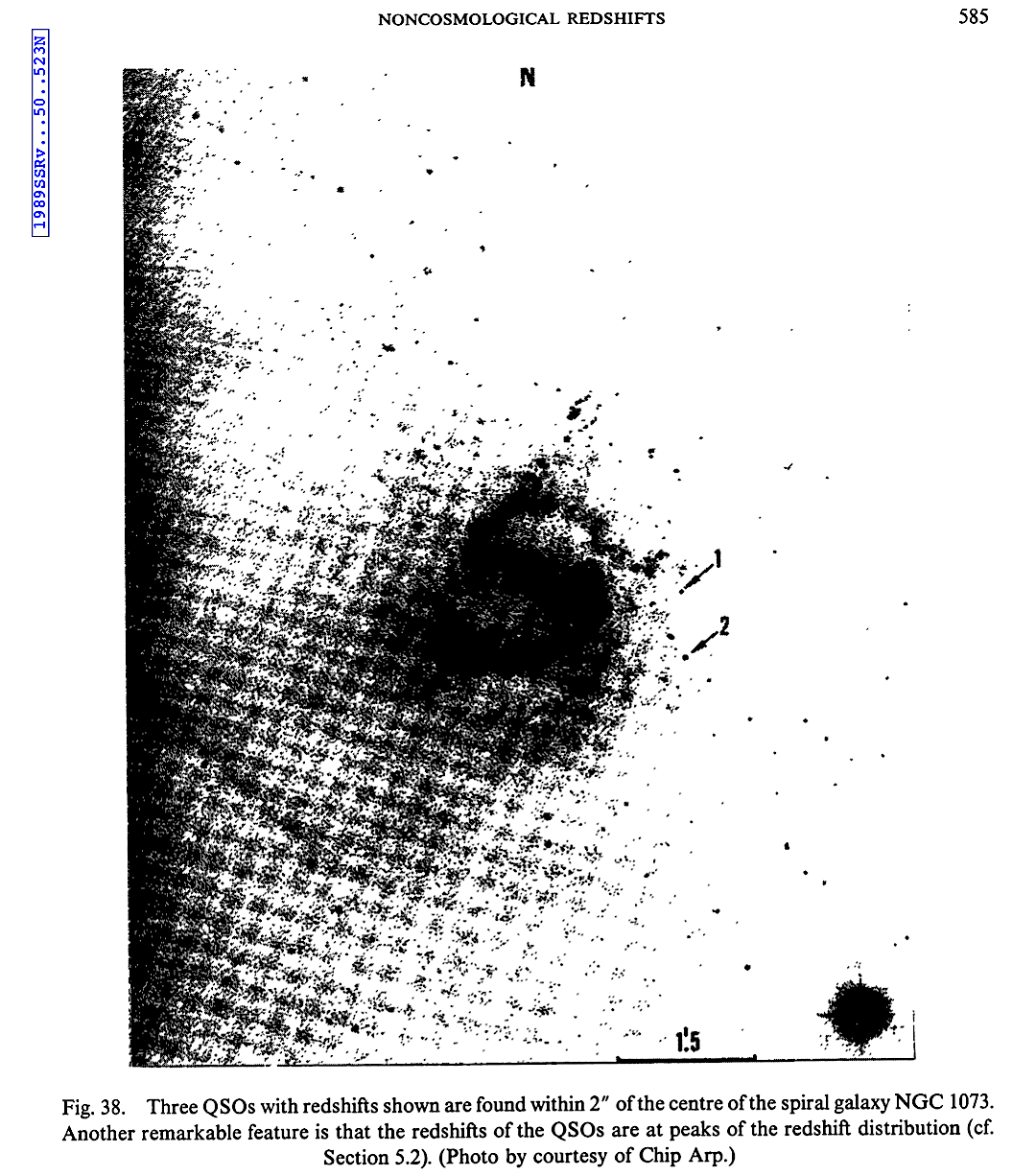

Furthermore, quasars began to be found in close apparent connection with nearby, lower redshift galaxies. Low redshift, barred spiral galaxy NGC 1073 with three putatively associated, high redshift QSOs (discovered by H. Arp; cited in Burbidge et al. 1999). Note the alignment of the quasars with the spiral arms. We will return to this and similar associations. These ejection phenomena data will be explored further in Chapters IX (Vast jets and galactic ejection phenomena: Mass origin-ejection?) and X (Multiple galactic alignments: Ejections and galaxy clusters?).

(Arrows added to image from http://www.astronomy.com/asy/default.aspx?c=a&id=3430).

Another local, low redshift galaxy, NGC 3842, with three putatively-associated, more high redshift QSOs in juxtaposition (discovered by H. Arp; cited in Burbidge et al. 1999).

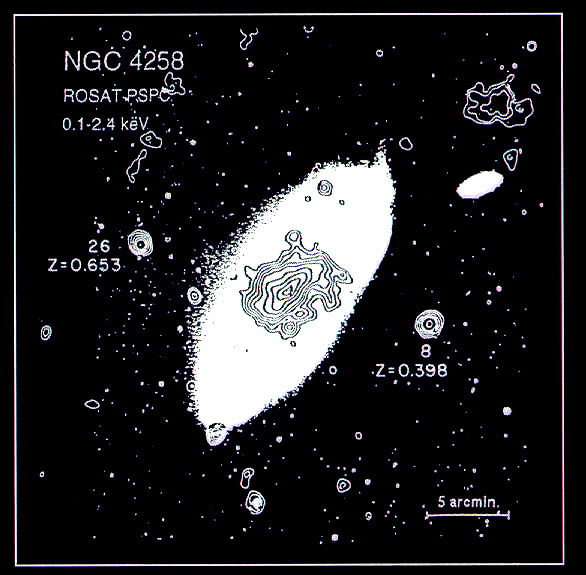

Higher redshift with nearly identical z-values, blue stellar objects in paired-alignment across the minor axis of the Seyfert galaxy NGC 4258 (cited by Arp, 1998 and Burbidge et al. 1999).

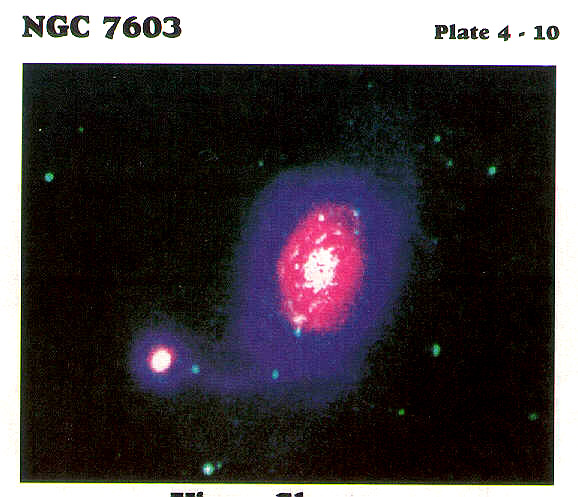

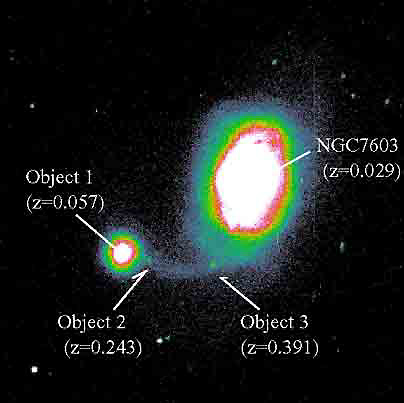

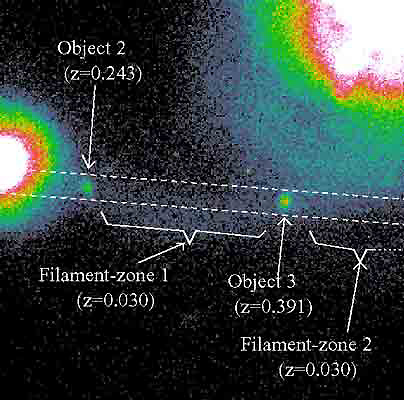

In 2002, two more high z objects were discovered in the NGC 7603 system, apparently associated with the same seeming ejection filament (Lopez-Corredoira & Gutierrez, 2002; https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361:20020476) indicating a decrease in z with distance from 'parent' galaxy (z = 0.391, 0.243, 0.057).

NGC 7603 & companions |

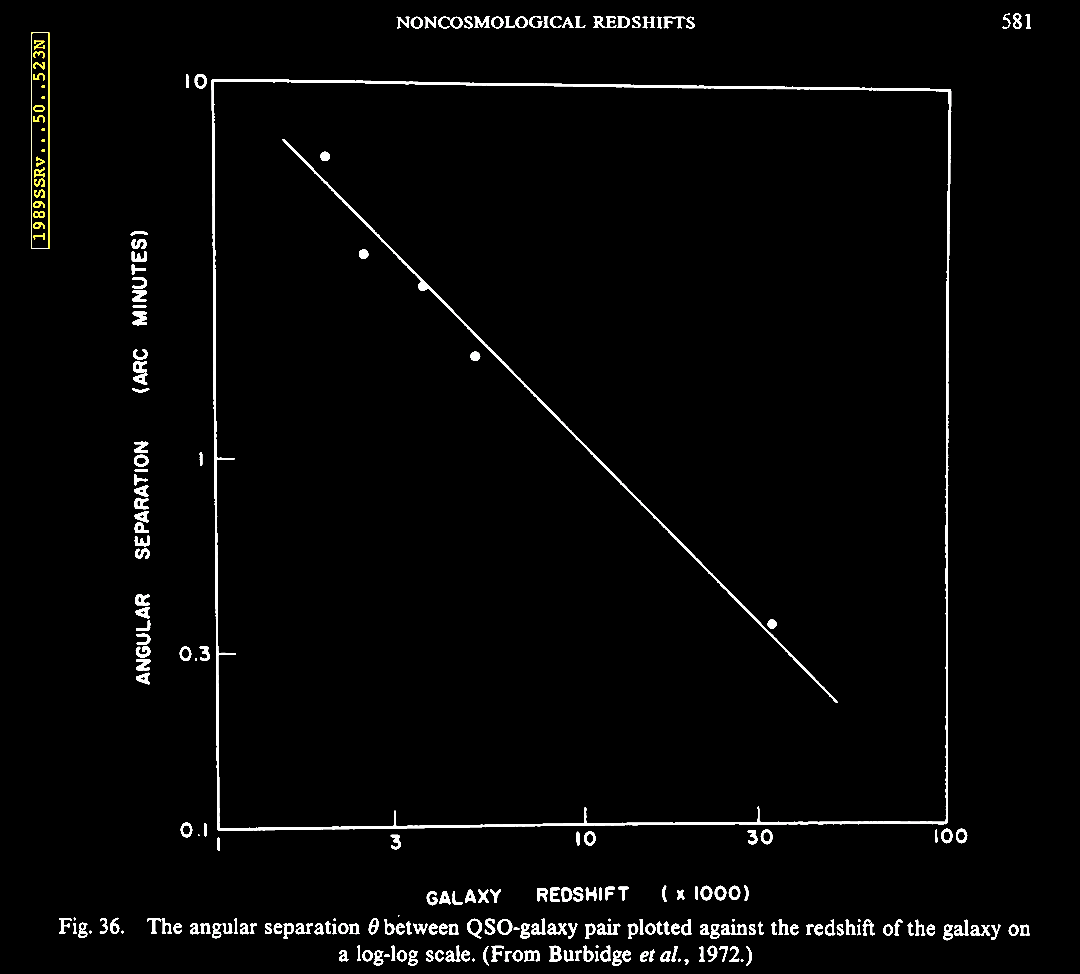

|

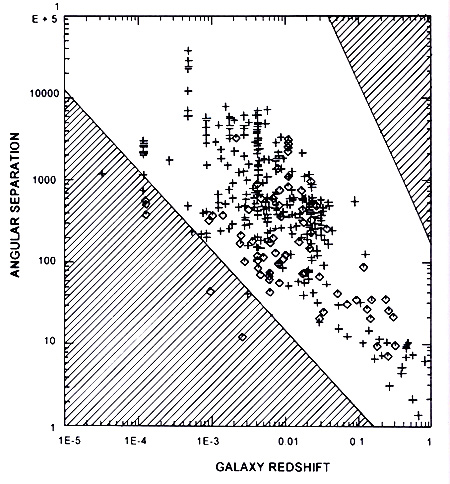

There is an observed pattern as illustrated in the redshift vs. angular separation for 392 galaxy-QSO pairs plotted on a logarithmic scale (Left figure in the following table), indicating an inverse relation between (ascending) angular measure and (descending) redshift, strongly indicative of ejection and at least some connection between higher z values and proximity to putative ejections / angular distance 'associations.'

Hatched

regions indicate areas excluded by selection effect,

i.e., determining whether a galaxy-QSO 'pair' is

actually observed. |

In another study, about

300 galaxy-QSO pairs were plotted by angular

separation (modified from Burbidge et al.

1990; Narlikar 1993). The dotted line indicates what

would be expected from a random background

distribution of QSOs without any pairing or galaxy-QSO

associations. |

In

yet another study, 197 galaxy-QSO pairs were plotted by

angular separation, and again, the non-random pattern of

association was assayed (Burbidge et al., 1990;

Hoyle et al. 2000). |

We will return to the recurring anomalous associations of low redshift galaxies, often with active galactic nuclei (AGNs), with higher redshift companion galaxies and galactic objects. These are often associated in ways which strongly suggest ejection and recurring ejection events. See Chapter IX. Vast jets and Galactic Ejection Phenomena: Mass origin-ejection?.

Another anomalous redshift phenomenon?

A distant galaxy, STIS 123627, apparently had a changing redshift interpreted as 12.1 Gly distant down to a nearer 9 Gly (Joseph, 2010a). If this is real, it is again more evidence of a non-distance related z values. |

(iv) Unusual

redshift periodicities which won't go away.

[Image from Burbidge, G. 2003. NGC 6212, 3C 345, and other Quasi-stellar Objects associated with them.

ApJ 586, L119. https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.1086/374793/fulltext/16874.text.html#crf14].

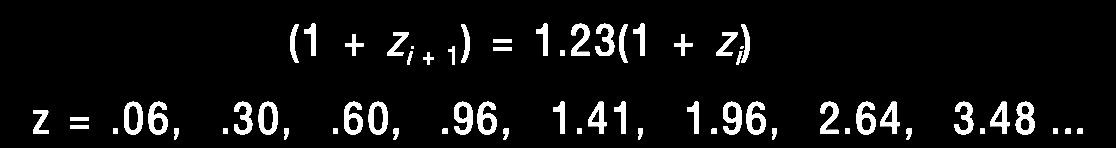

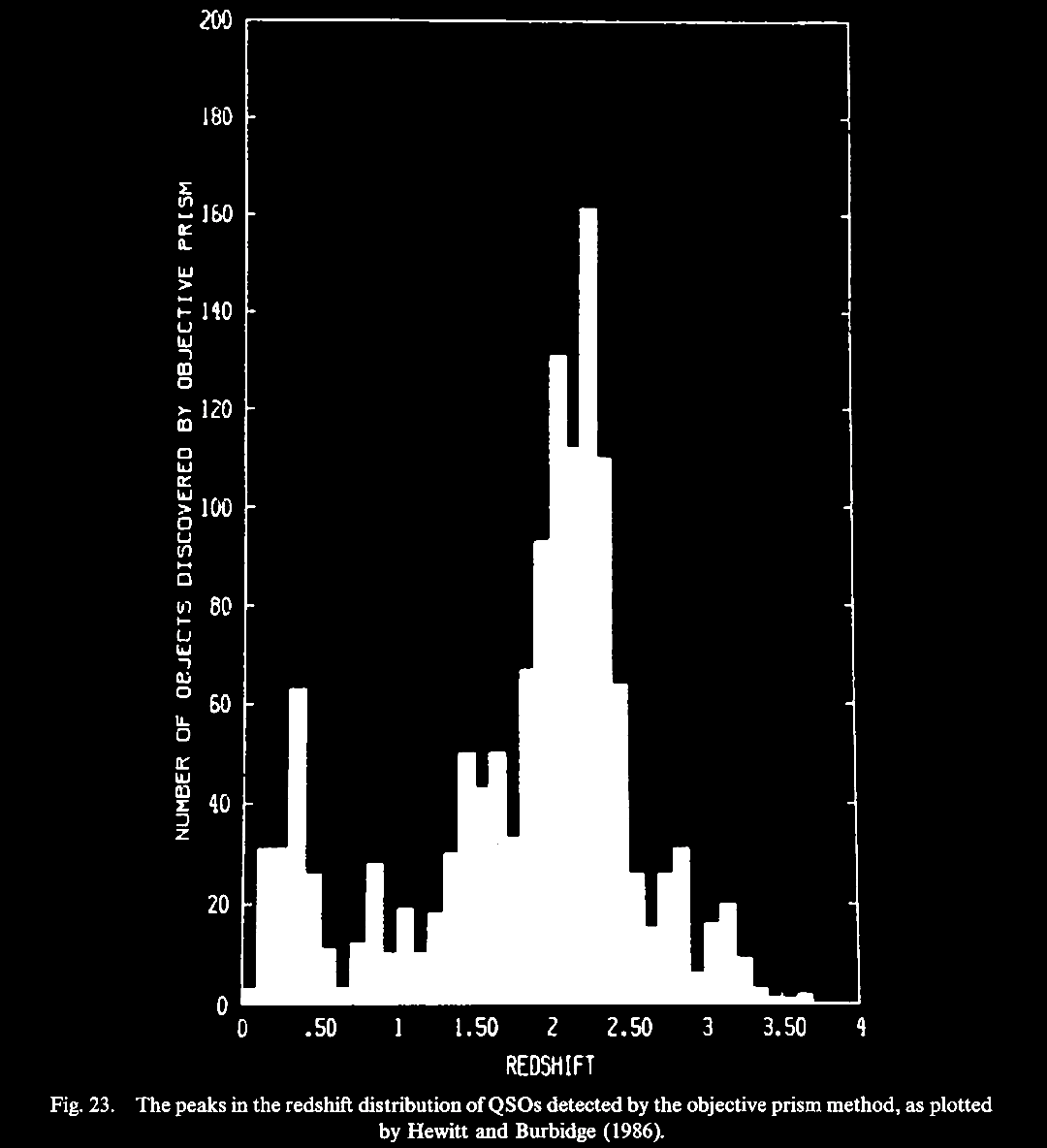

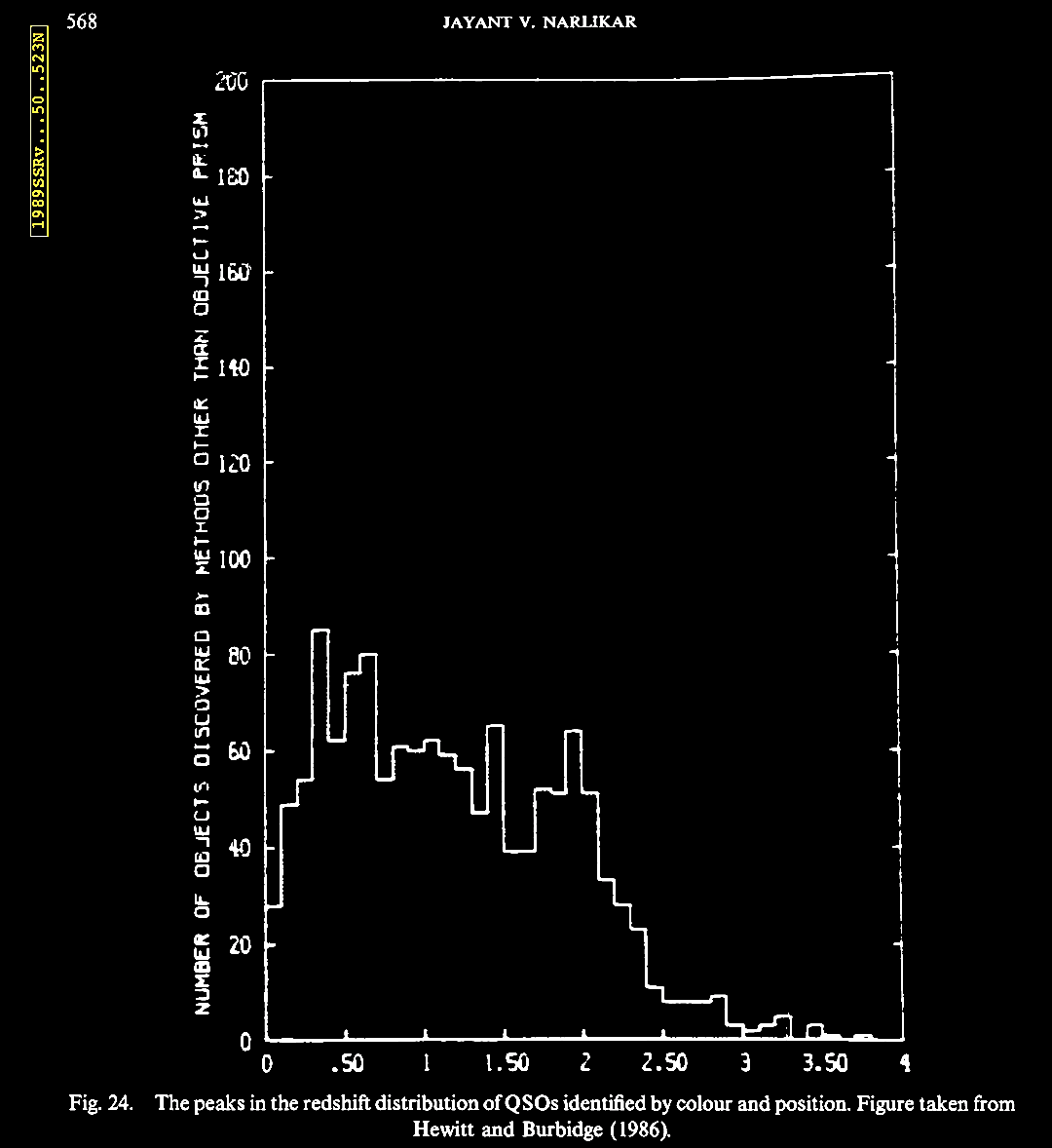

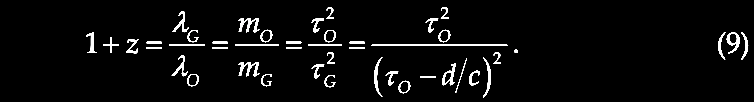

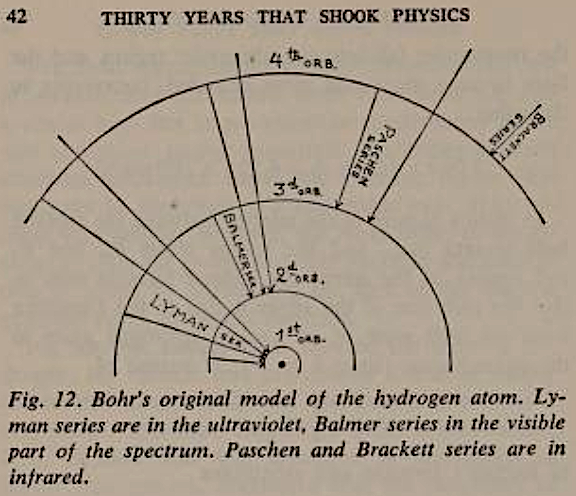

Brief Excursus on the Ambartsumian-Vorontsov-Vel'yaminov-Arp (AVVA) galactic ejection cosmogony hypothesis (for more, see forthcoming Chapter IX). Cf. Arp, 2003. Catalogue of Discordant Redshift Associations; pp. 13-16. The clustering of redshift quantities around certain "preferred values" was discovered by Burbidge & Burbidge (1967. Limits to the distance of the Quasi-Stellar Objects deduced from their absorption line spectra. ApJ 148, L107. https://www.adsabs.harvard.edu/full/1967ApJ). K. G. Karlsson (1971. Possible discretization of quasar redshifts. Astron. Astrophys. 13, 333. https://adsabs.harvard.edu/pdf/1971) showed that these discrete values follow an empirical relationship, (1 + z2) / (1 + z1) = 1.23, where z1 = the lower redshift and z2 = the next higher redshift up (Arp, 1998. Seeing Red: Redshifts, Cosmology, and Academic Science. Apeiron Press; p. 203) yielding preferred redshift peaks or periodicities in a geometric series or Karlsson series, where z1 = or corresponds to zi and z2 = or corresponds to zi + 1, with terms reordered thus:

Karlsson showed that the first six elements of the series were observed in the available redshift data, and further he predicted the existence of the next higher peaks with values of z = 2.64 and 3.48. So, given that we repeatedly observe pairs of quasars or other higher redshift compact objects juxtaposed across the minor axis of lower redshift active galaxies as if ejected in pairs from the putative parent galaxy with its lower redshift (zG), suppose that we consider the putatively ejected pair of quasars with their measured redshifts (z1, z2) for example across NGC 4258 (in the figure above from Burbidge & Burbidge, 1997. Ejection of matter and energy from NGC 4258. ApJ 477, L13-L15. https://doi.org/10.1086/310517, which is discussed in greater detail in chapter V), we can relate them to the parent galaxy redshift (zG) by correcting their redshifts to be in the reference frame or rest frame of the active center of the parent galaxy (zG), i.e., zQ, related by (1 + zQ) = (1 + z1) / (1 + zG). The difference between zQ and the next Karlsson peak in the series is assumed to predict the actual velocity of ejection, vej in units of c, that is, (1 + vej) = (1 + zQ) / (1 + zp), where zp = the redshift of that nearest Karlsson periodicity peak. For more details see forthcoming Chapter IX.

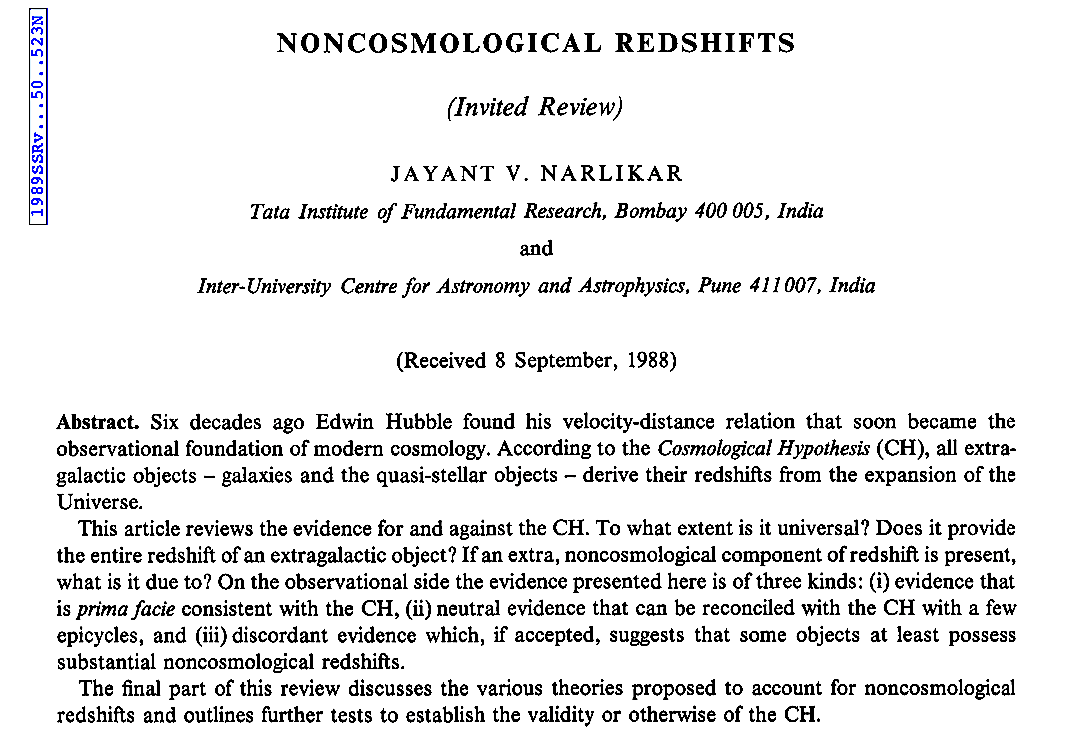

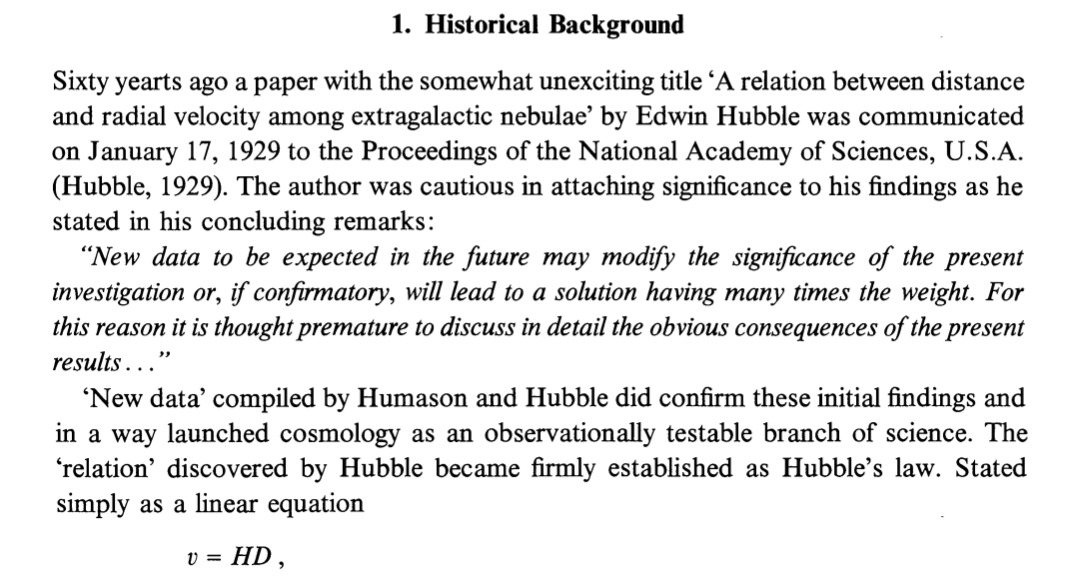

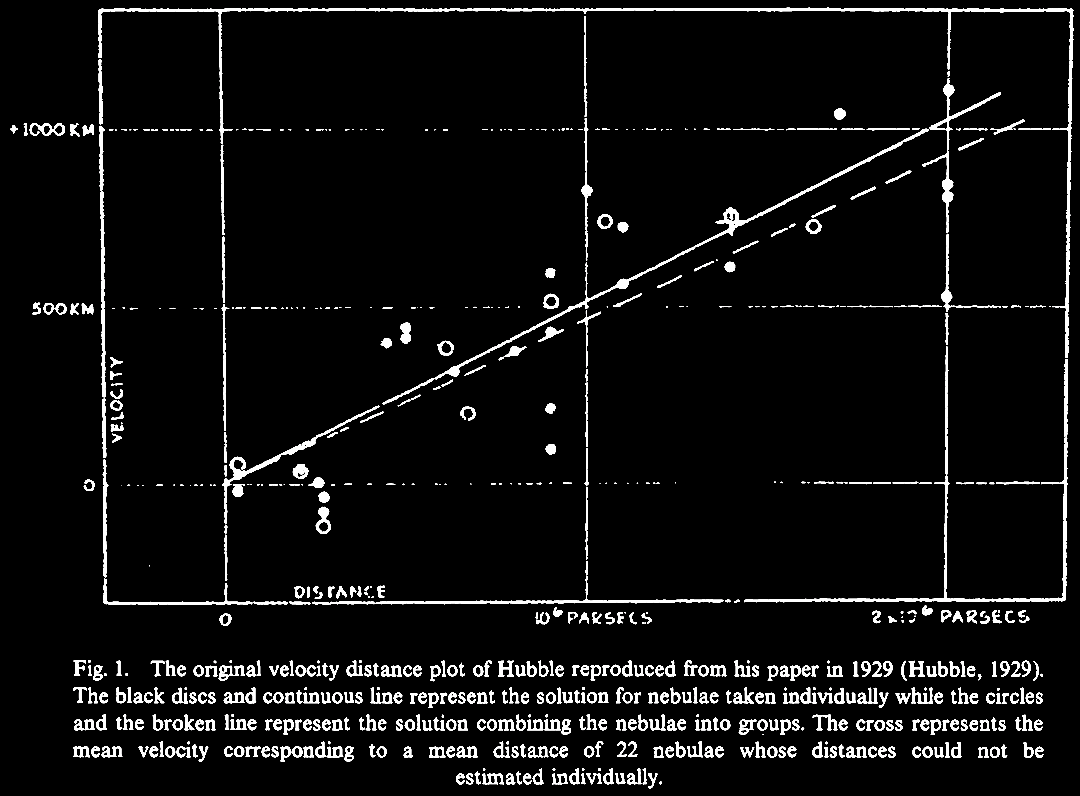

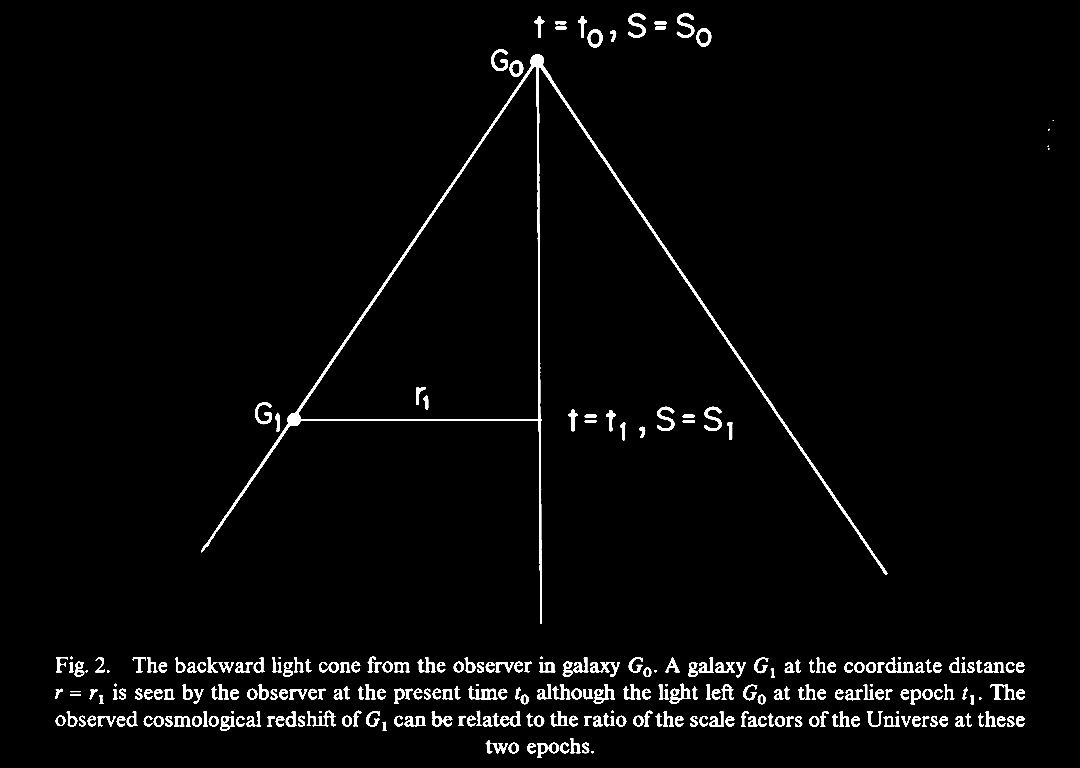

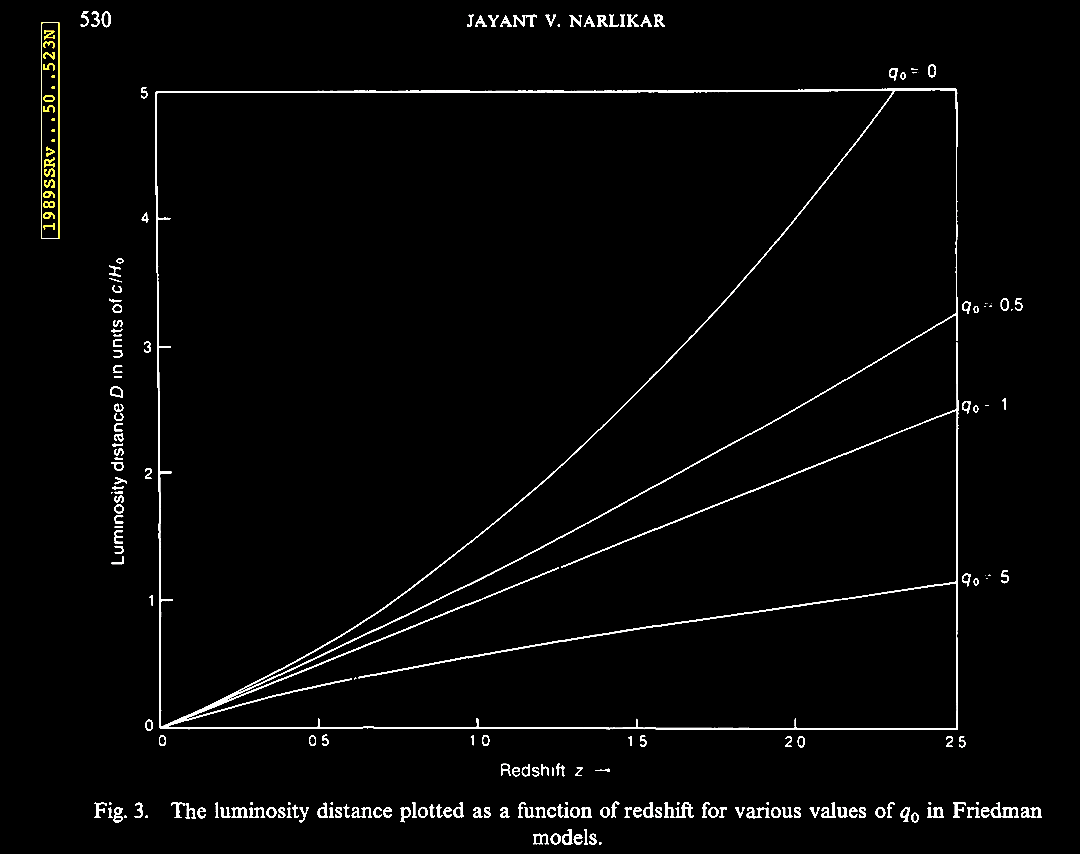

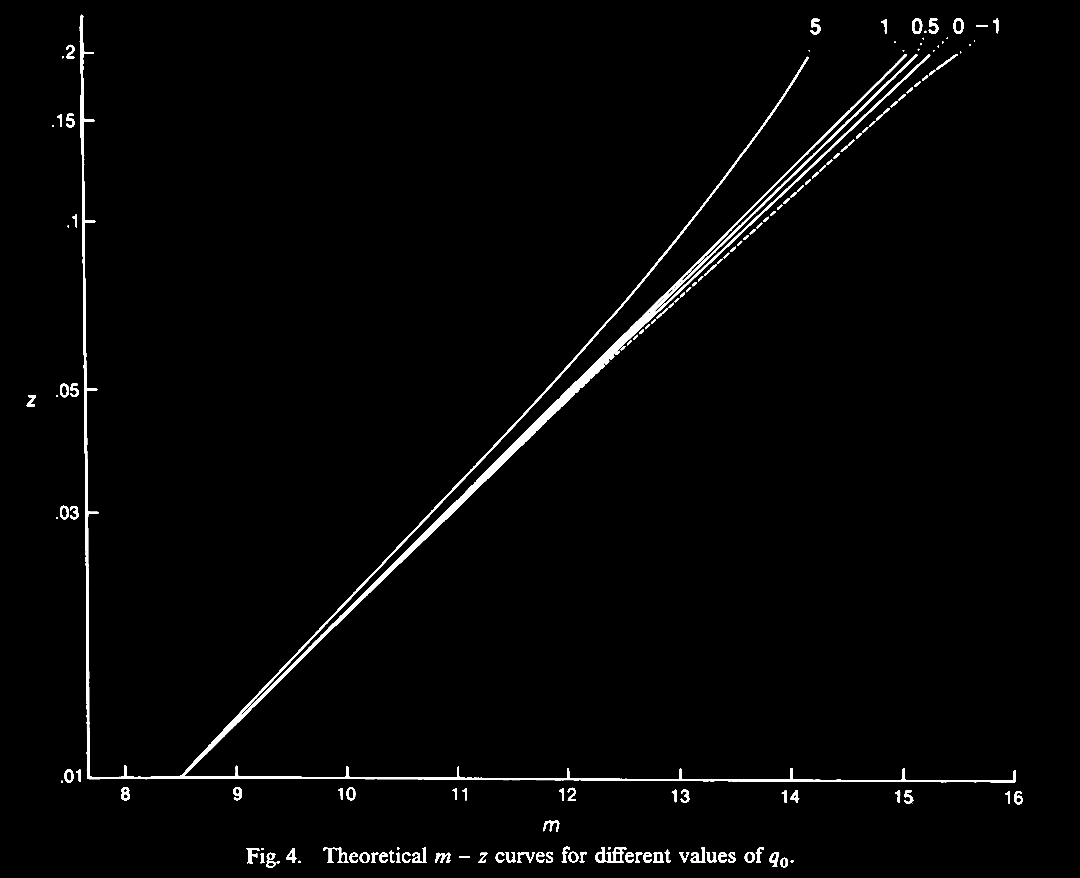

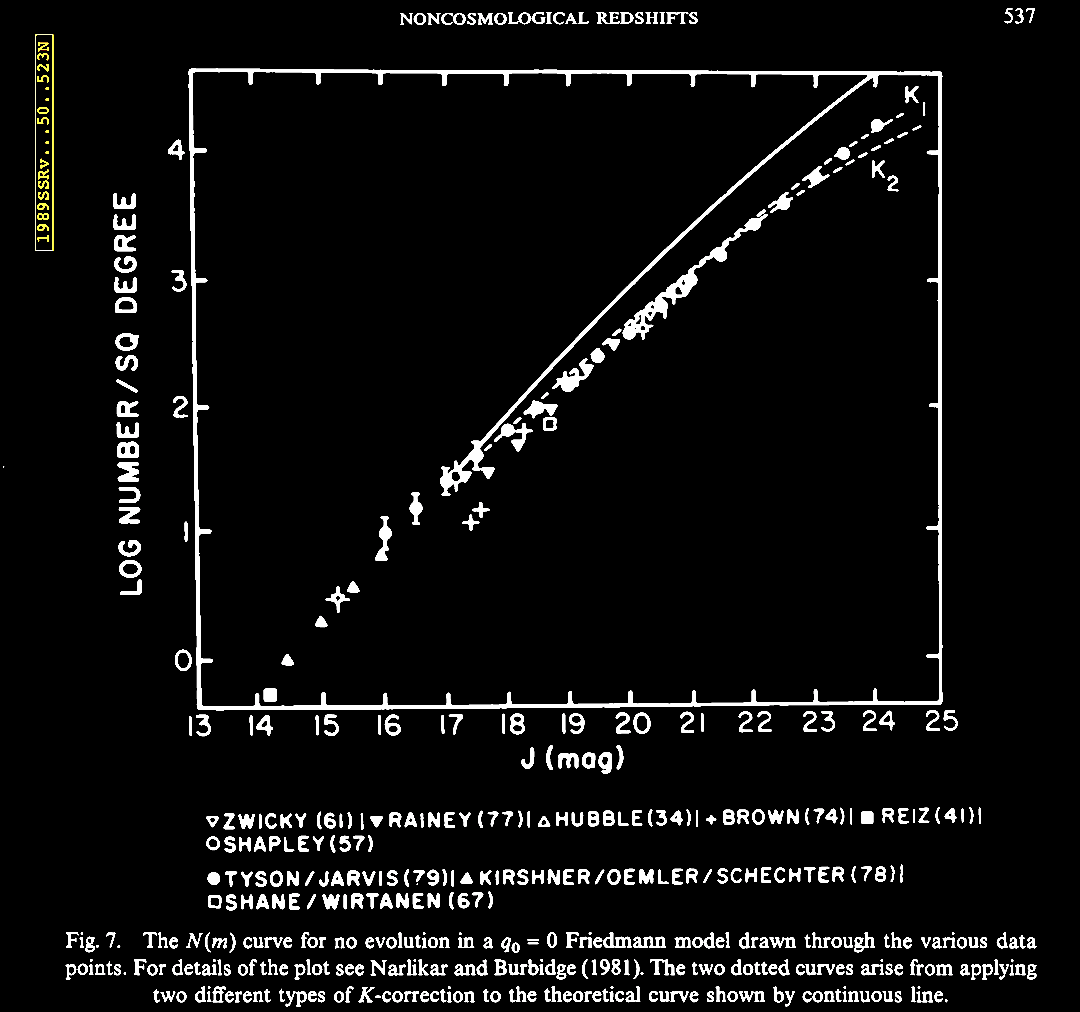

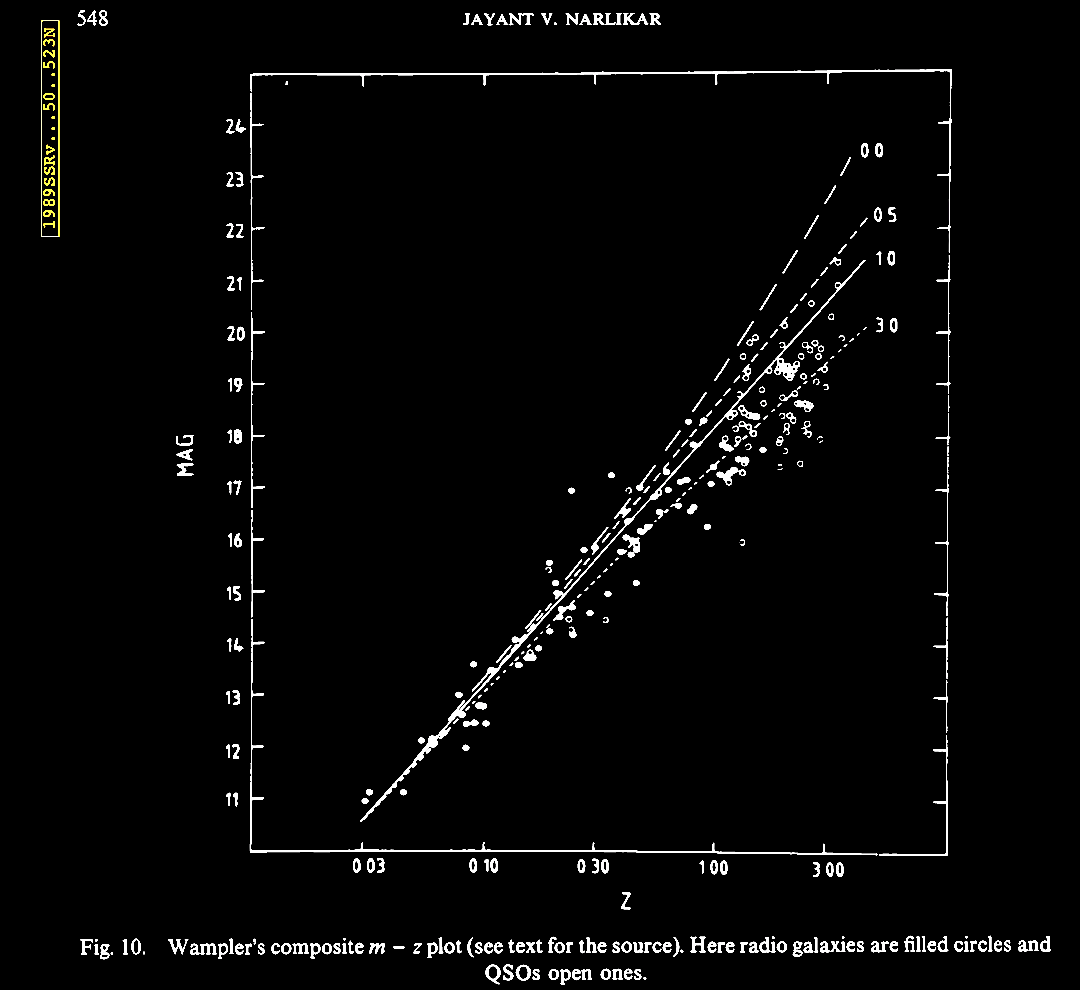

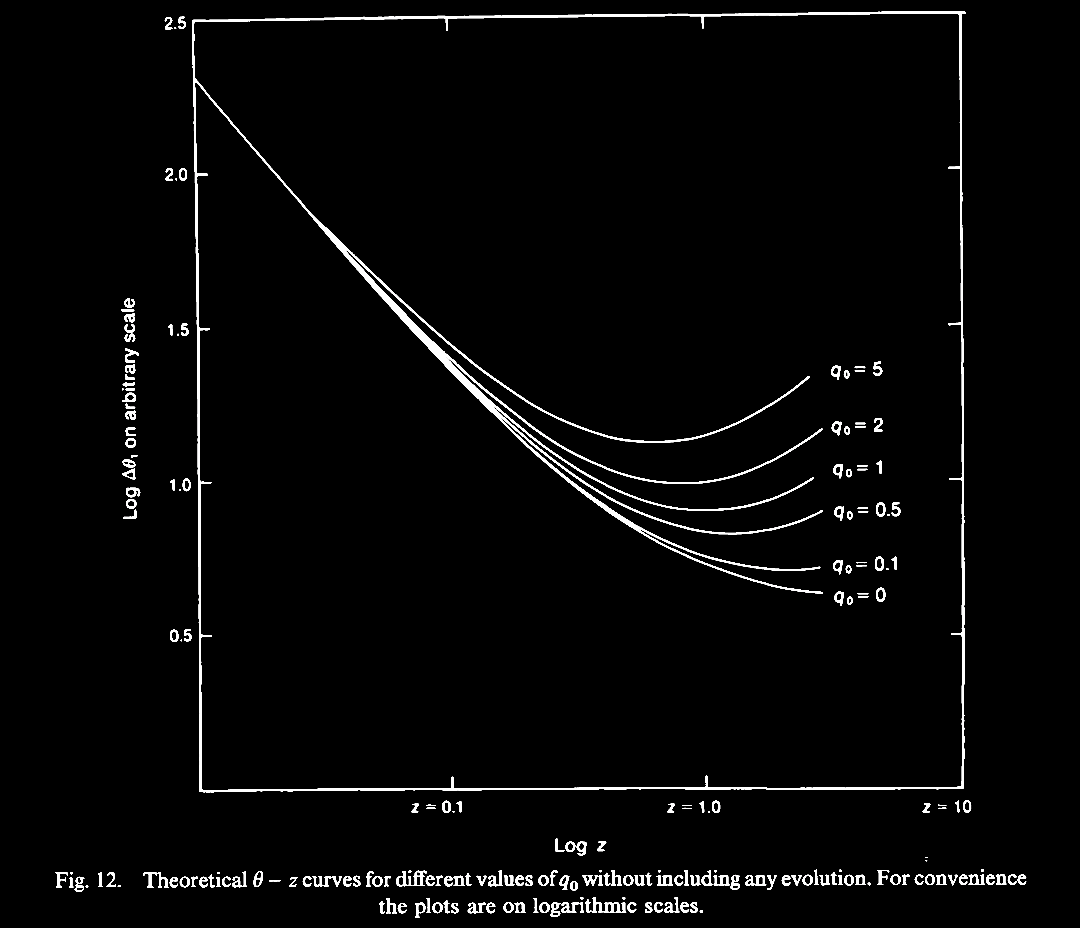

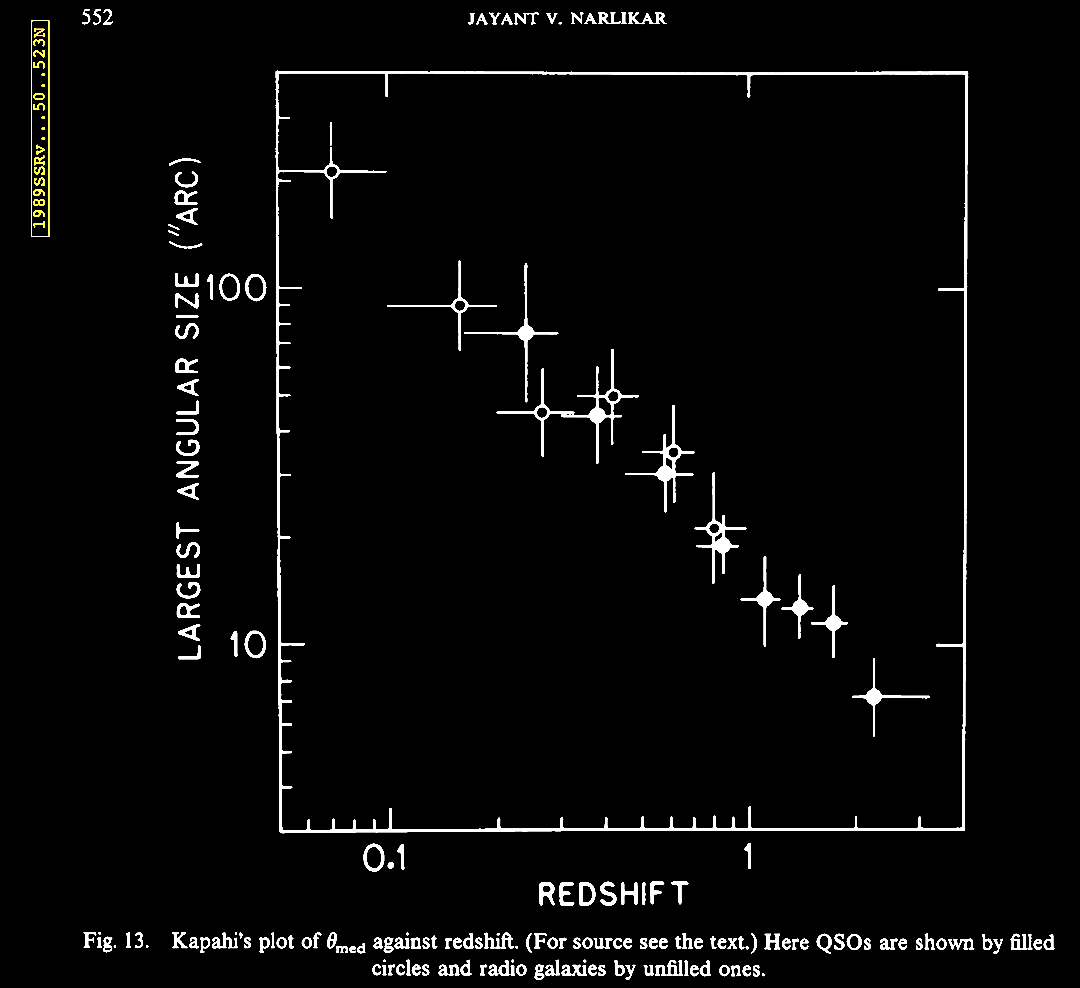

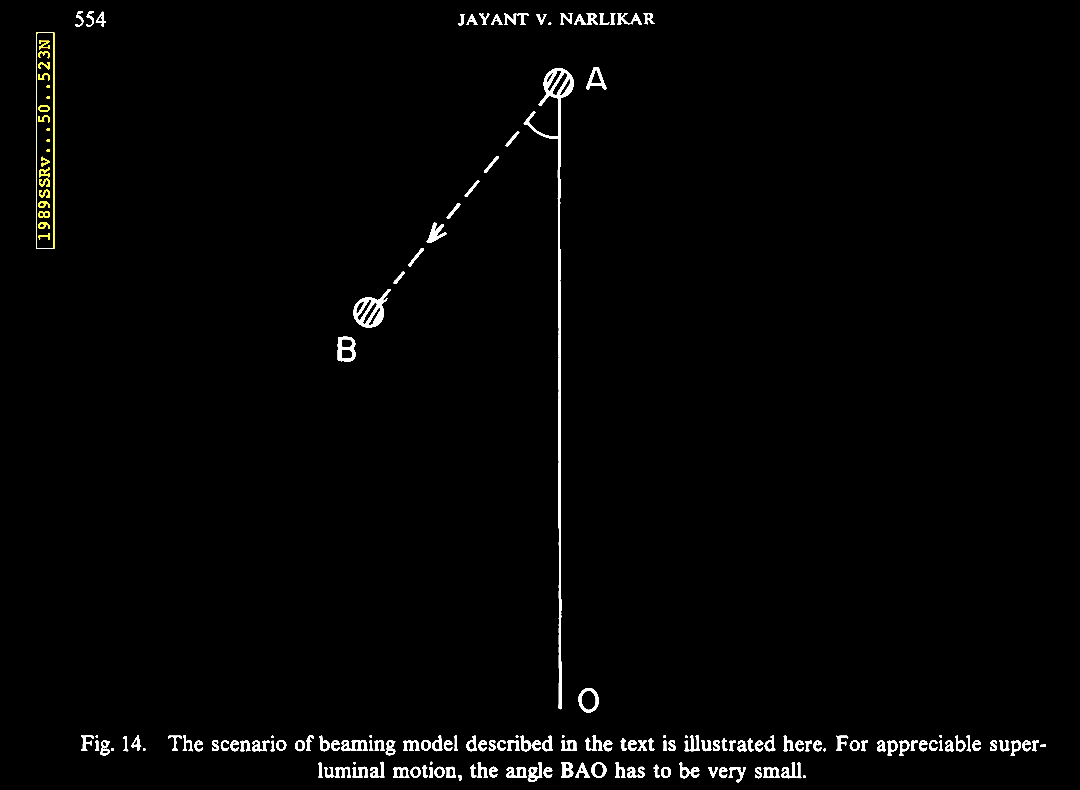

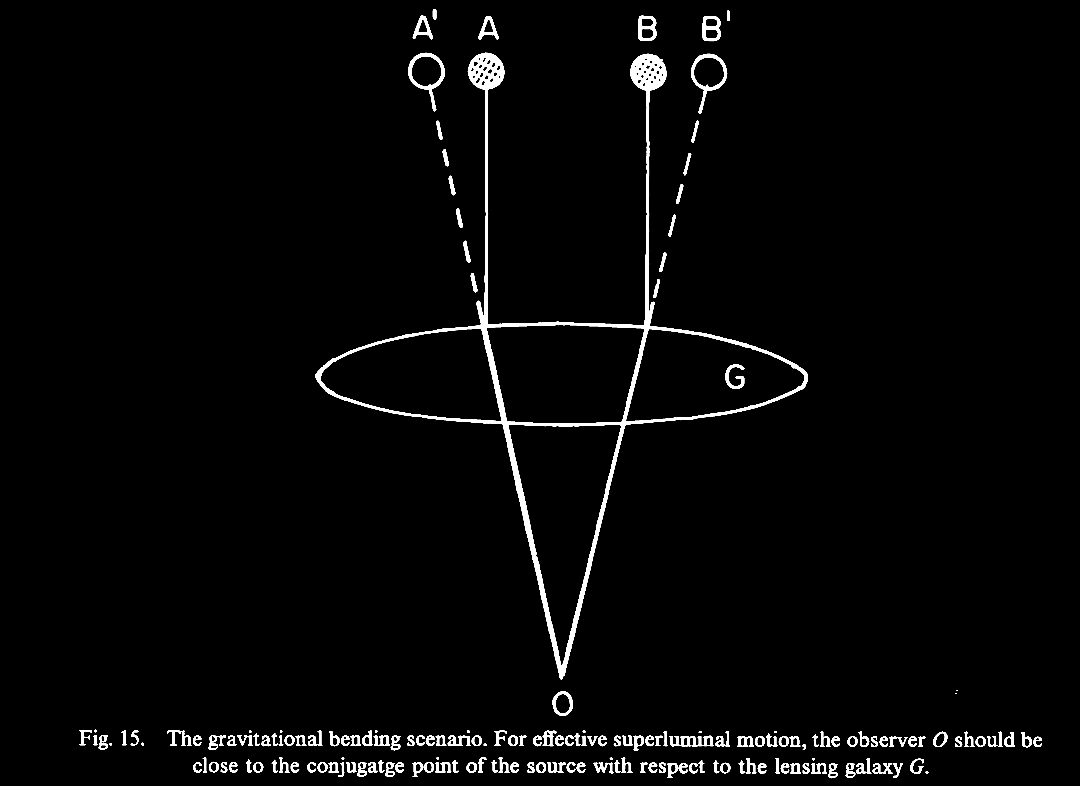

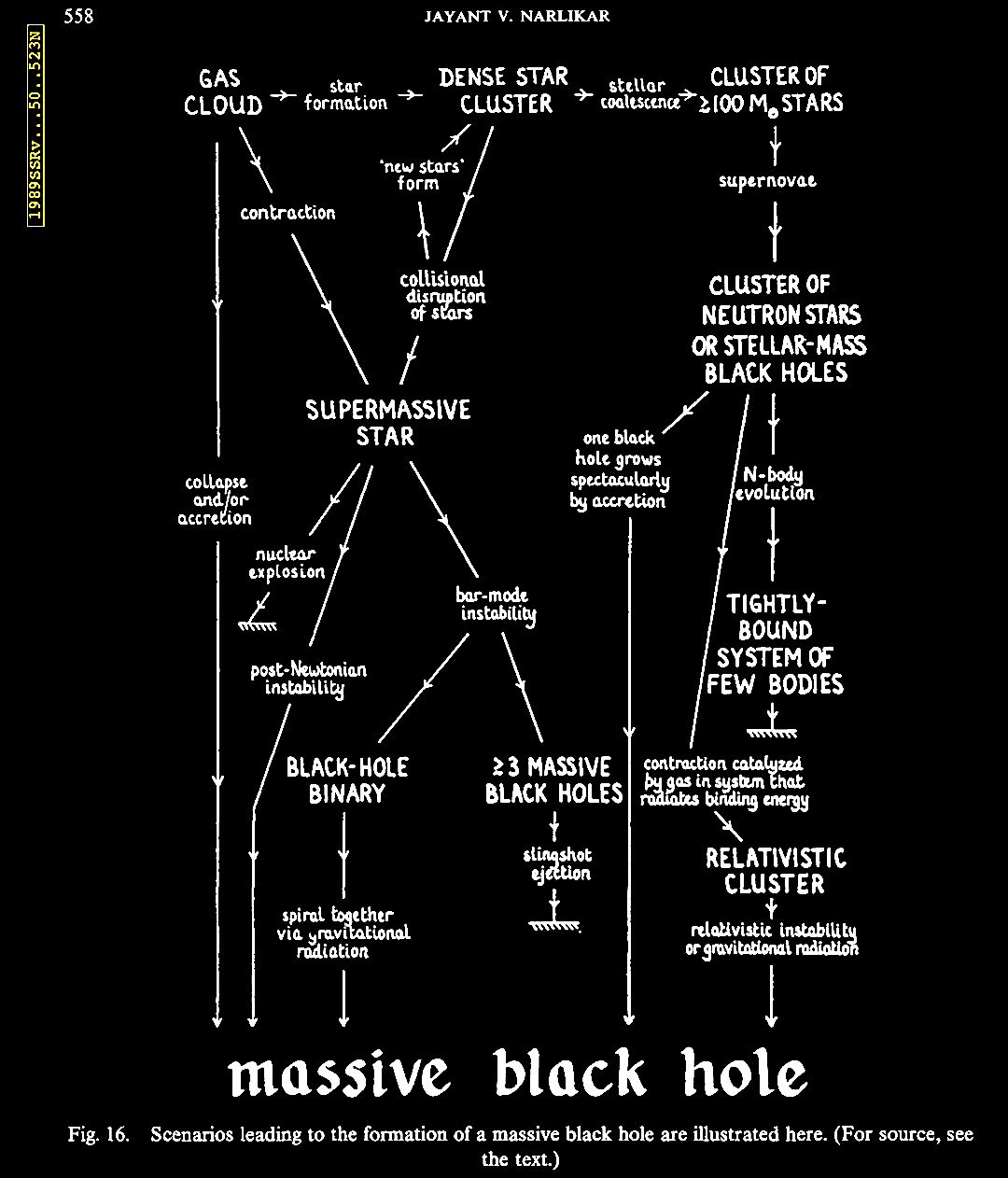

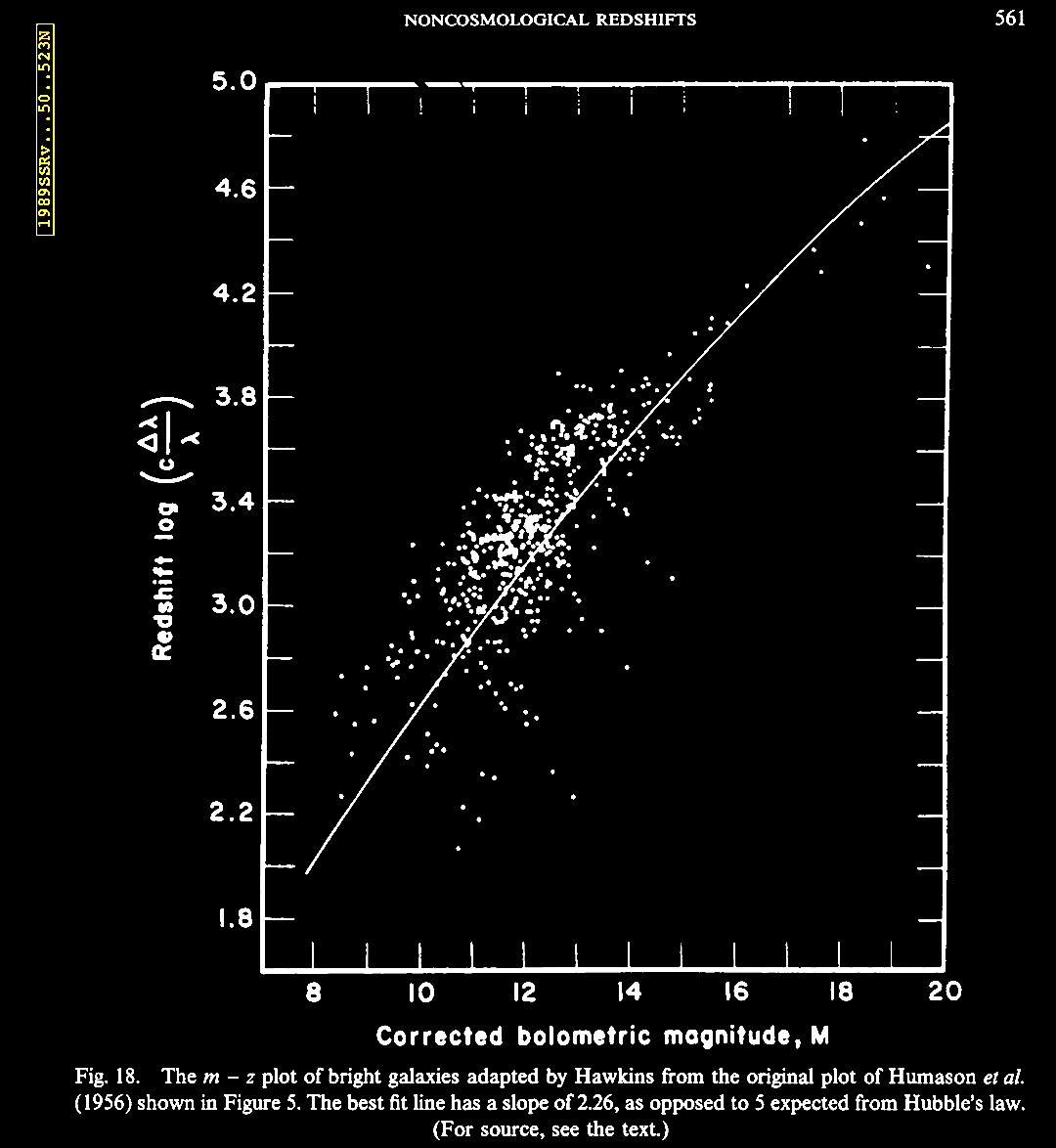

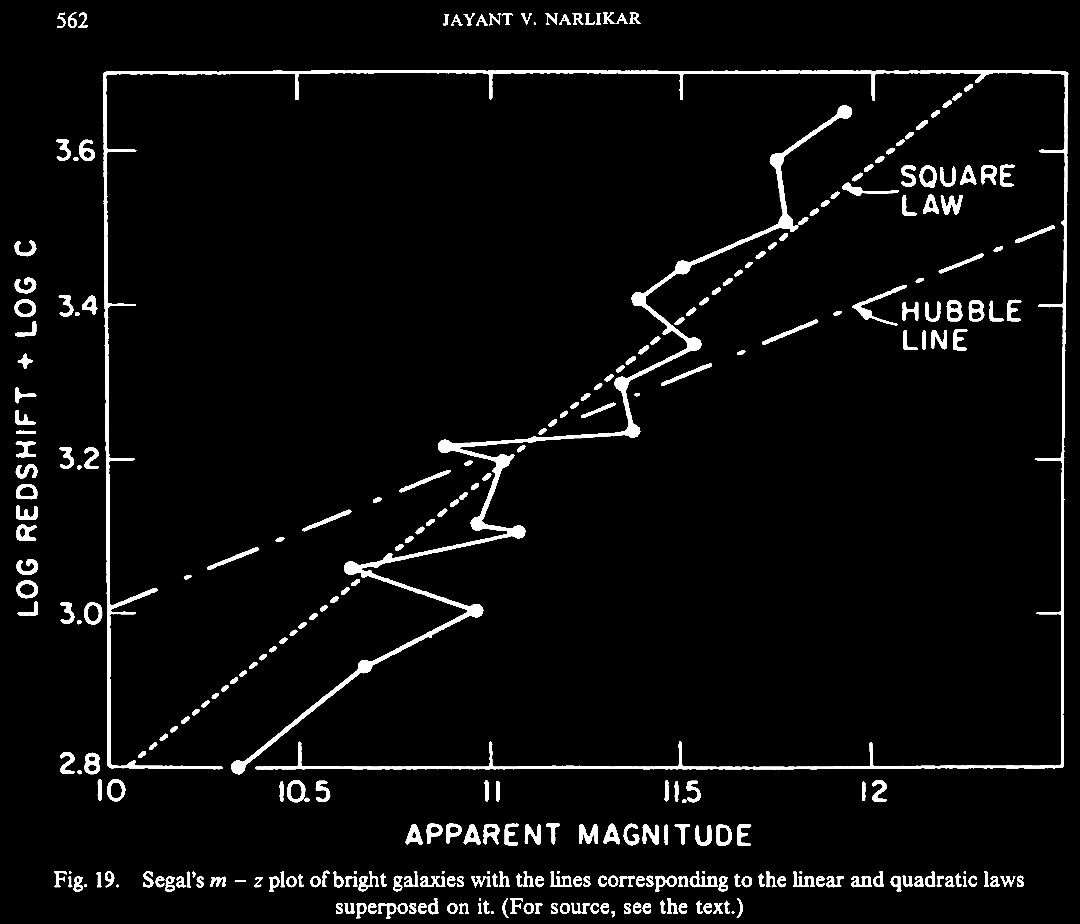

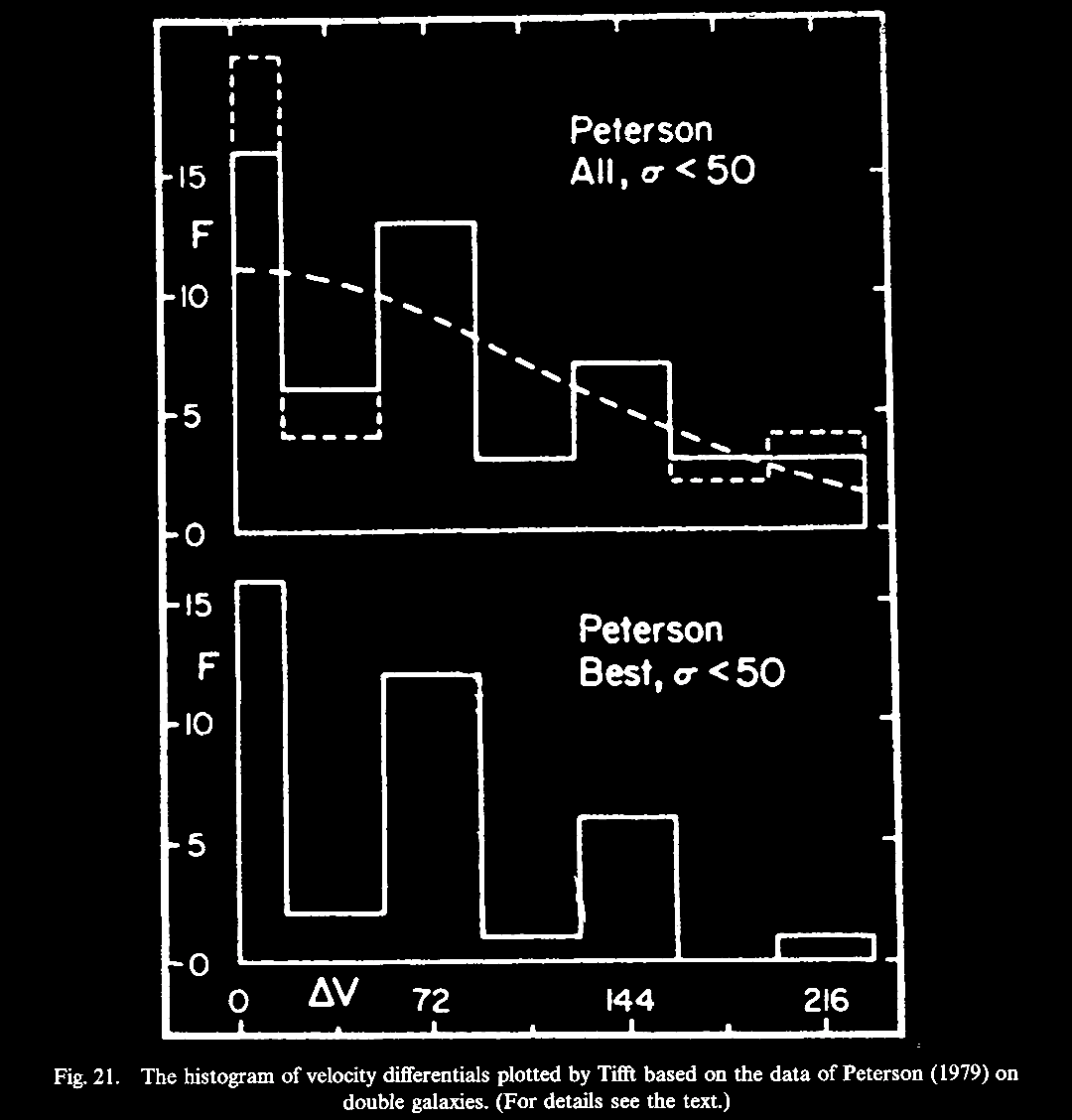

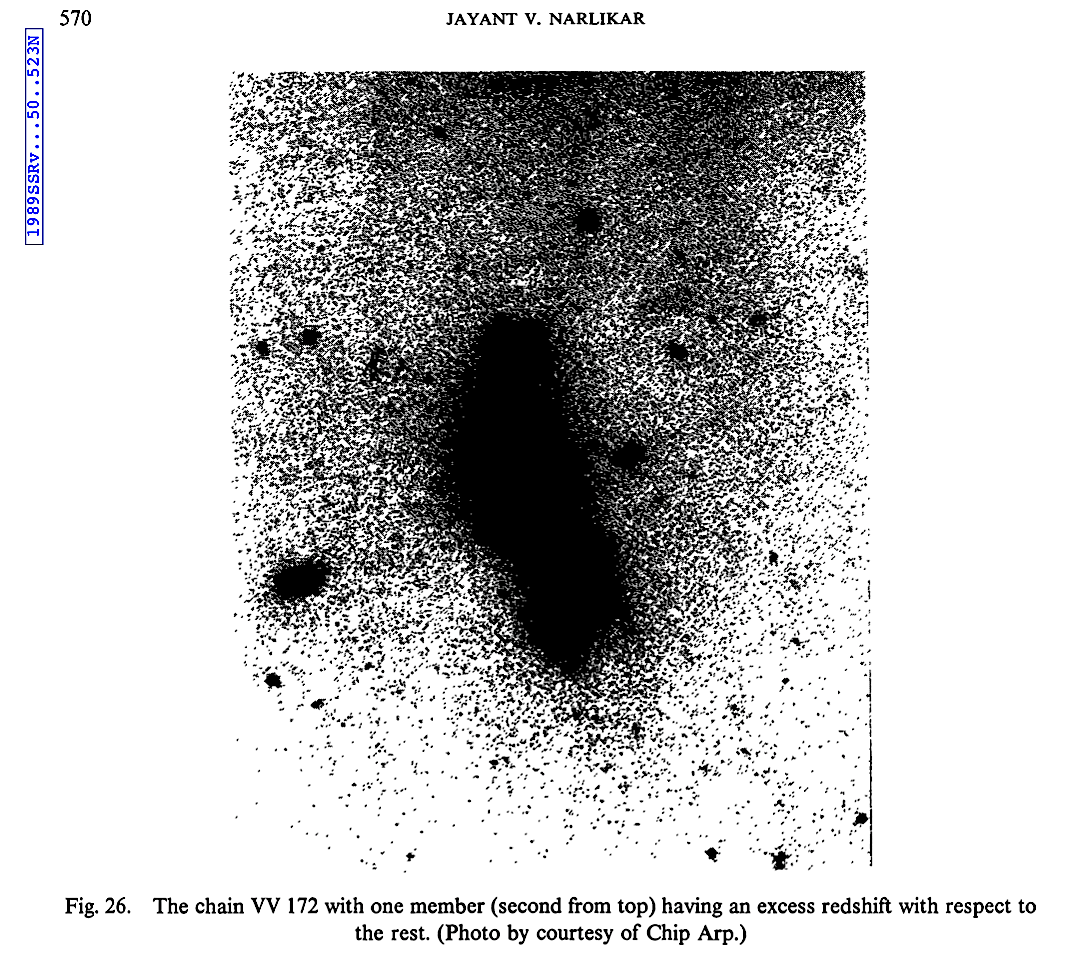

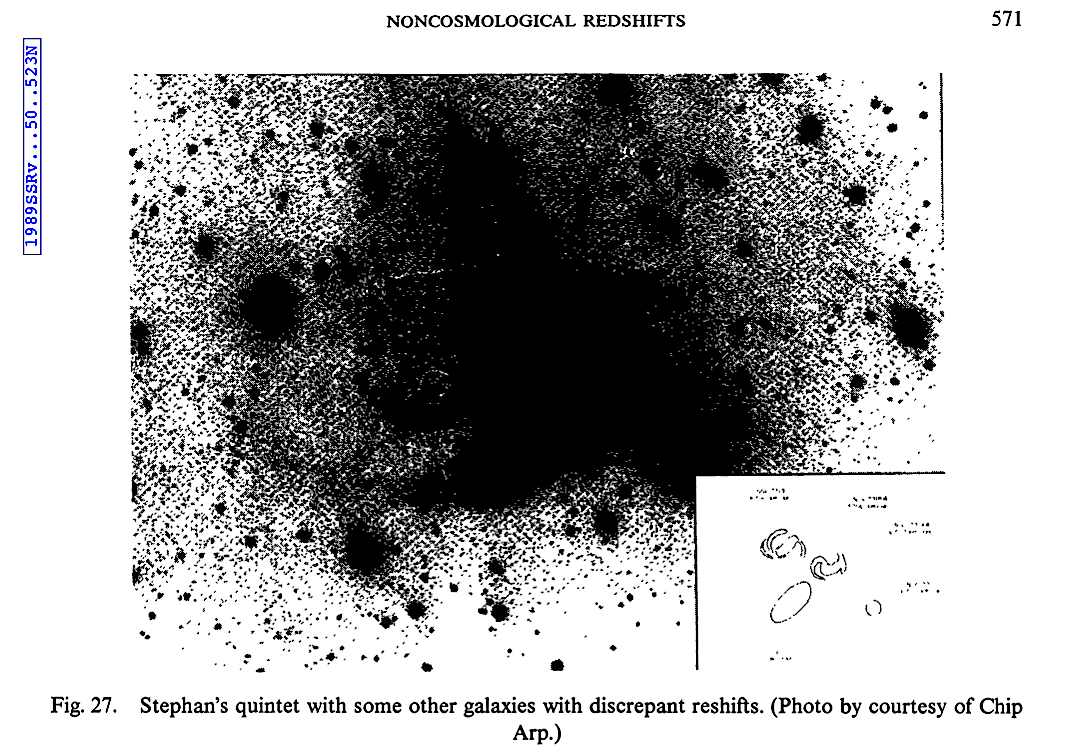

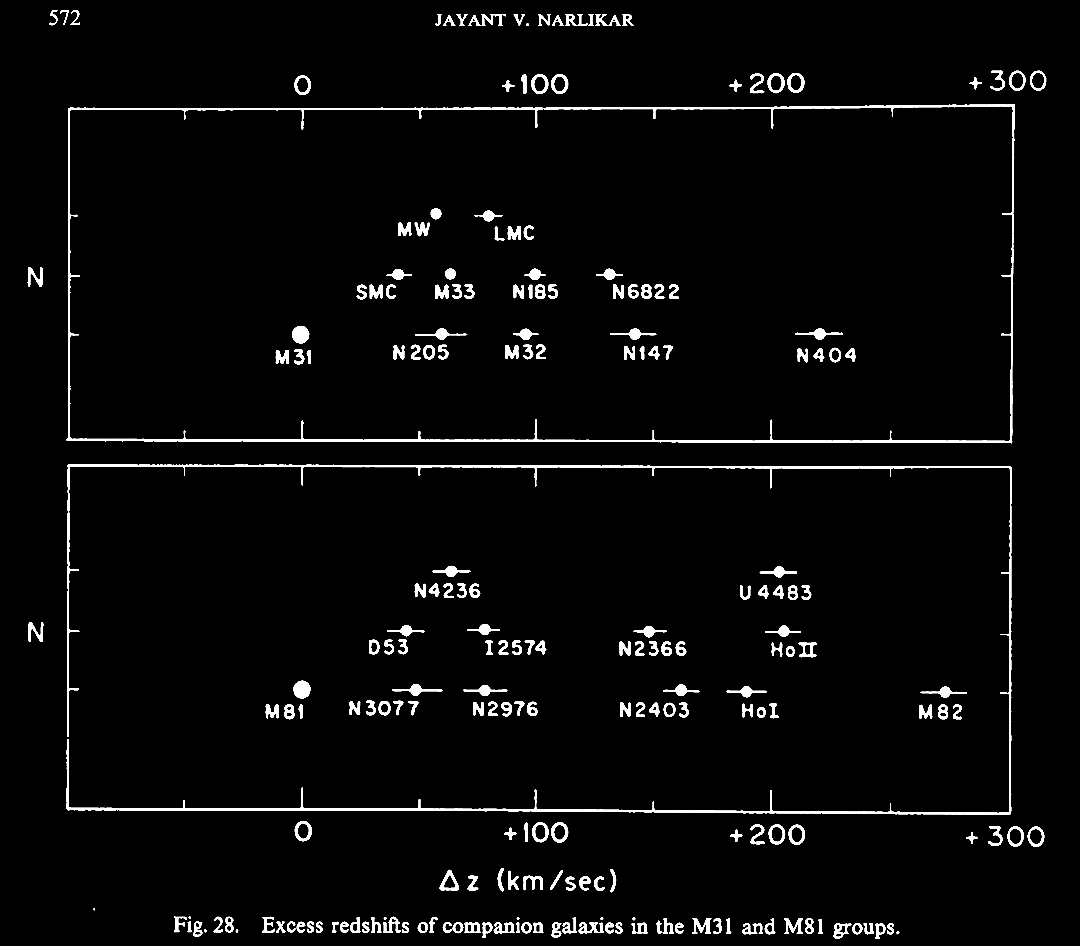

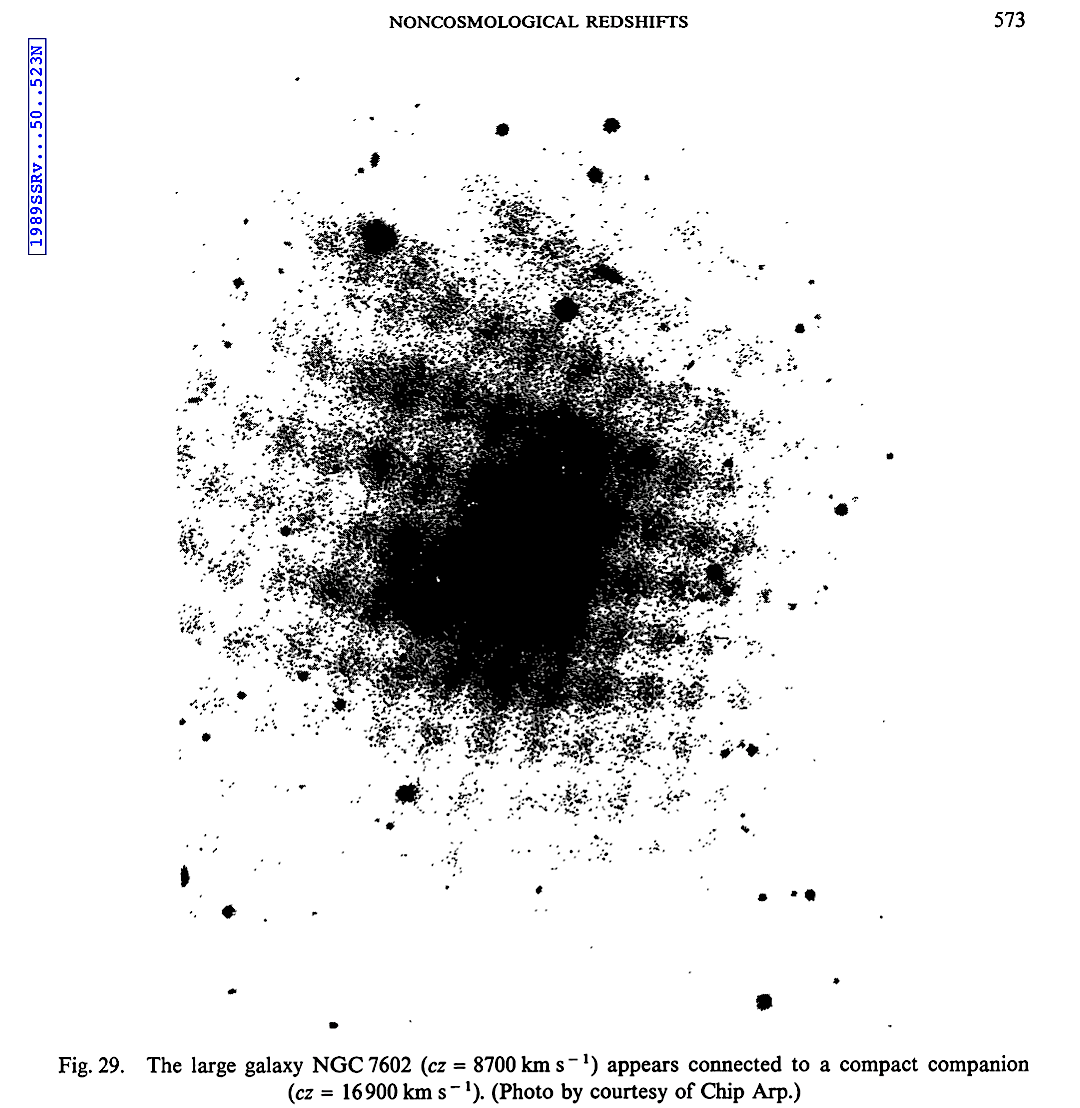

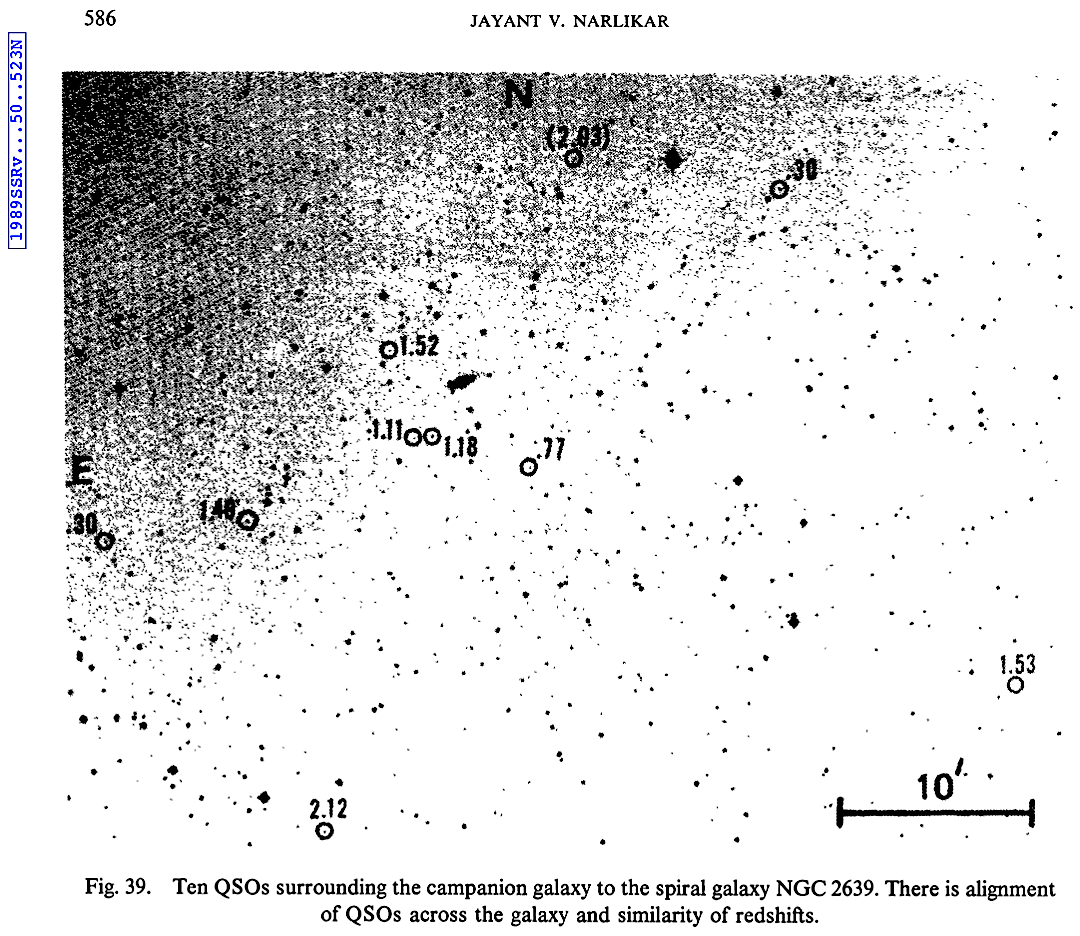

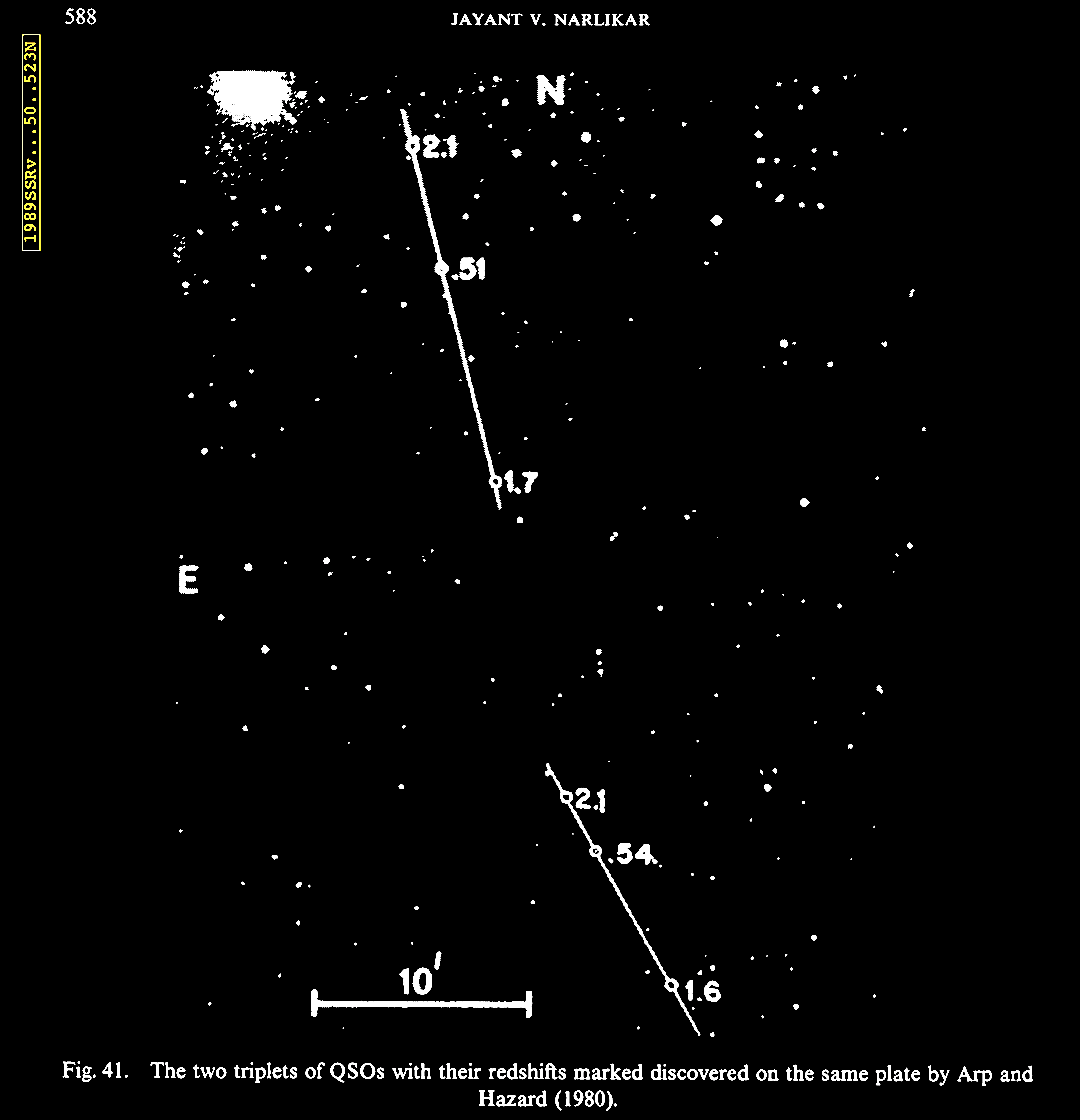

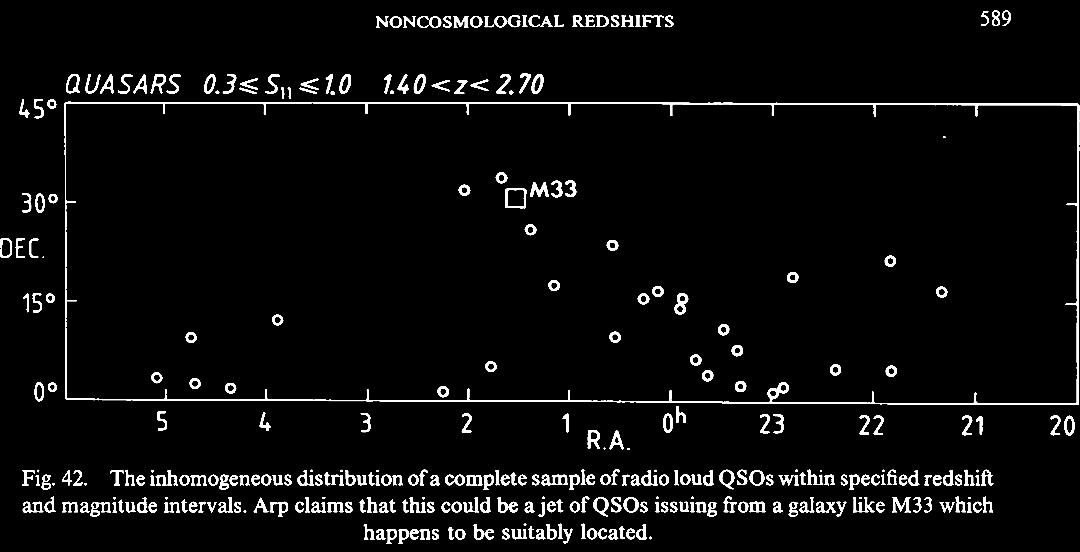

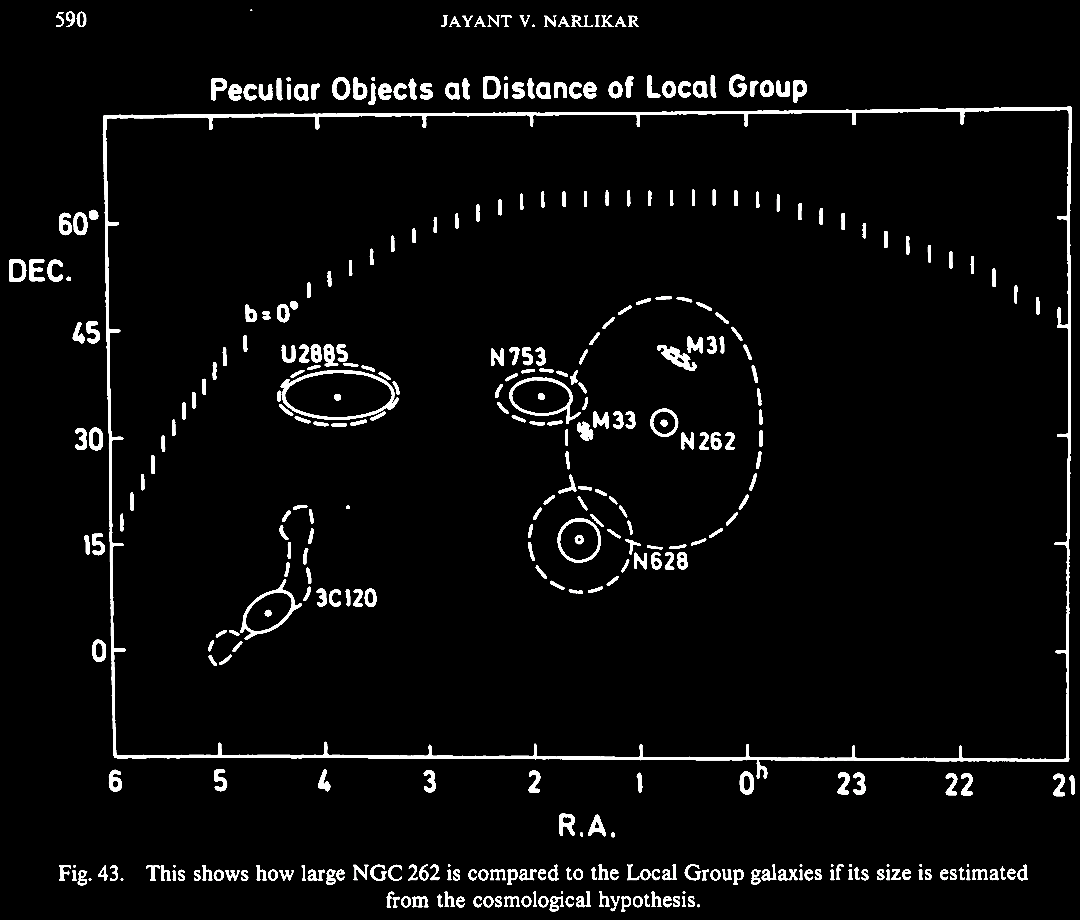

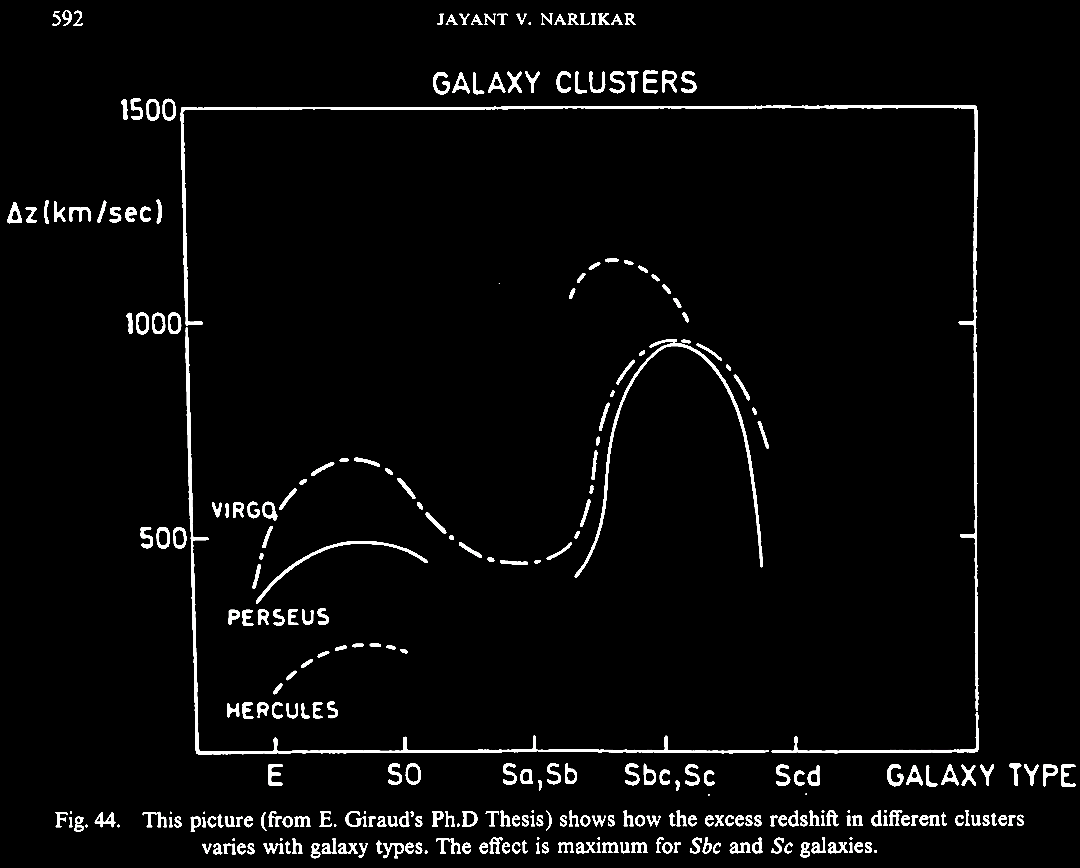

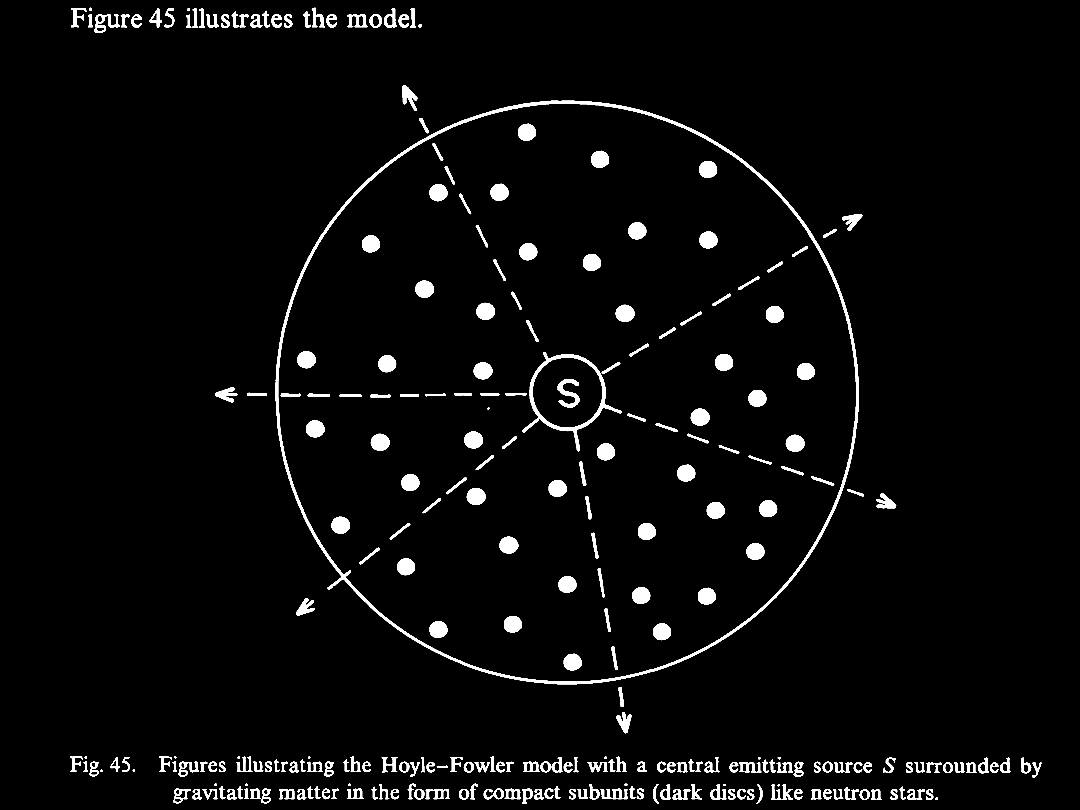

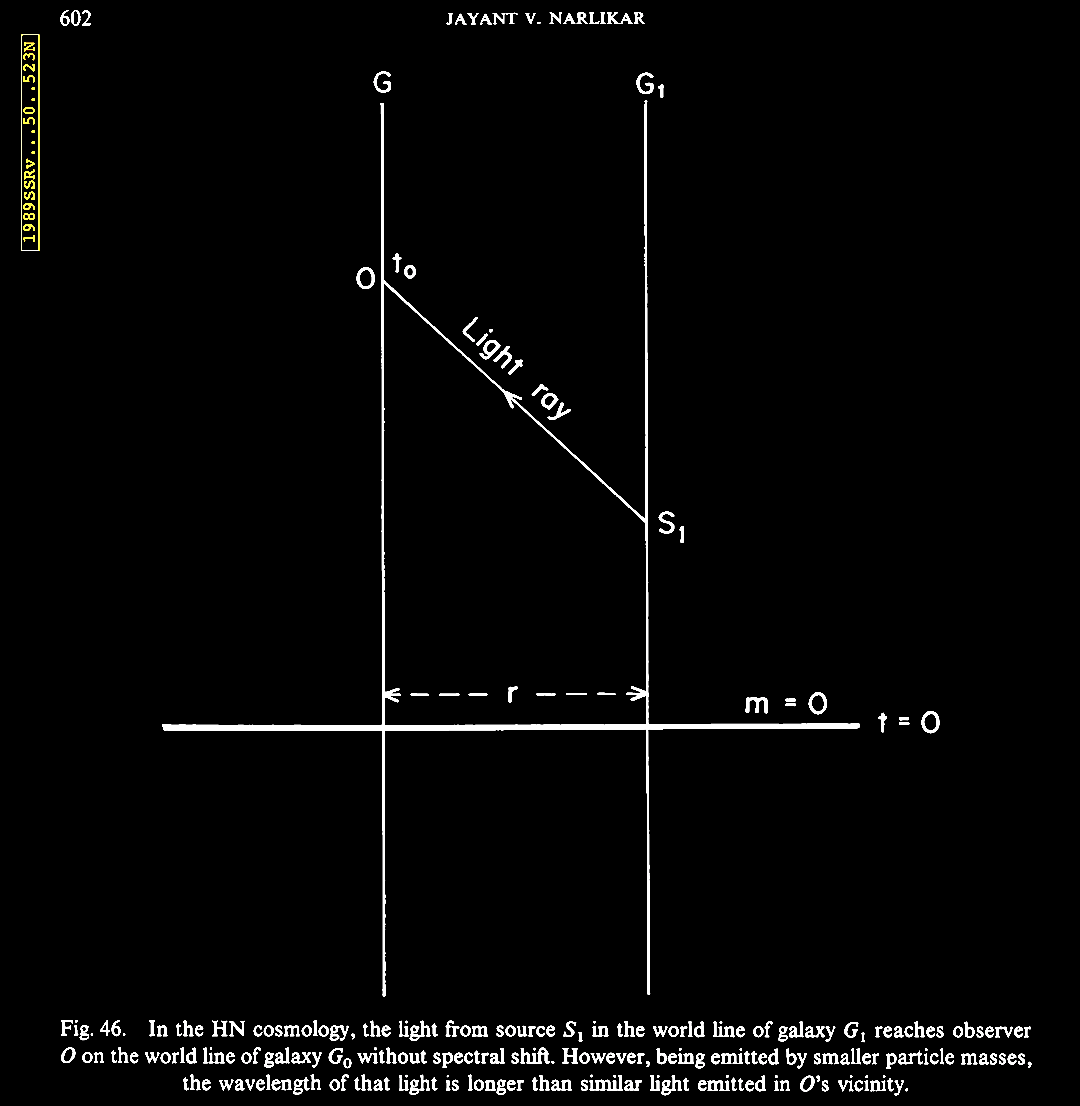

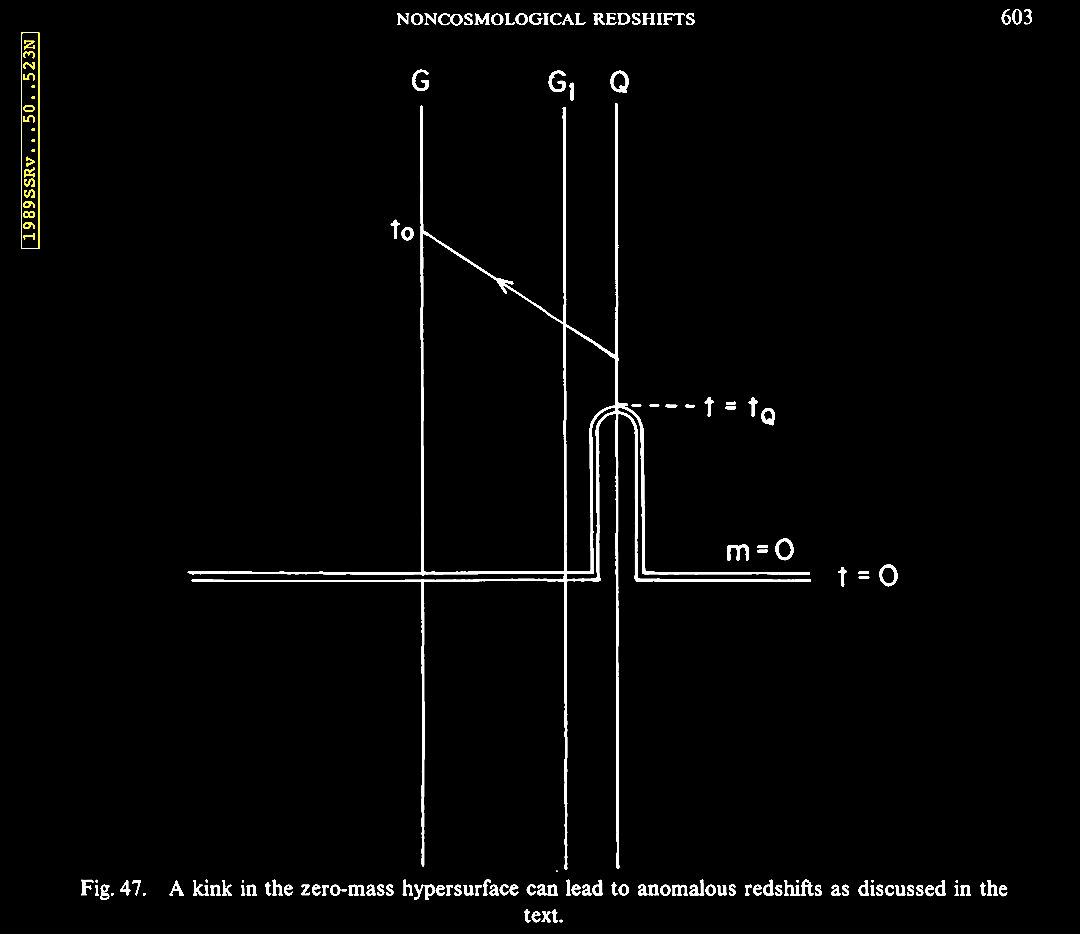

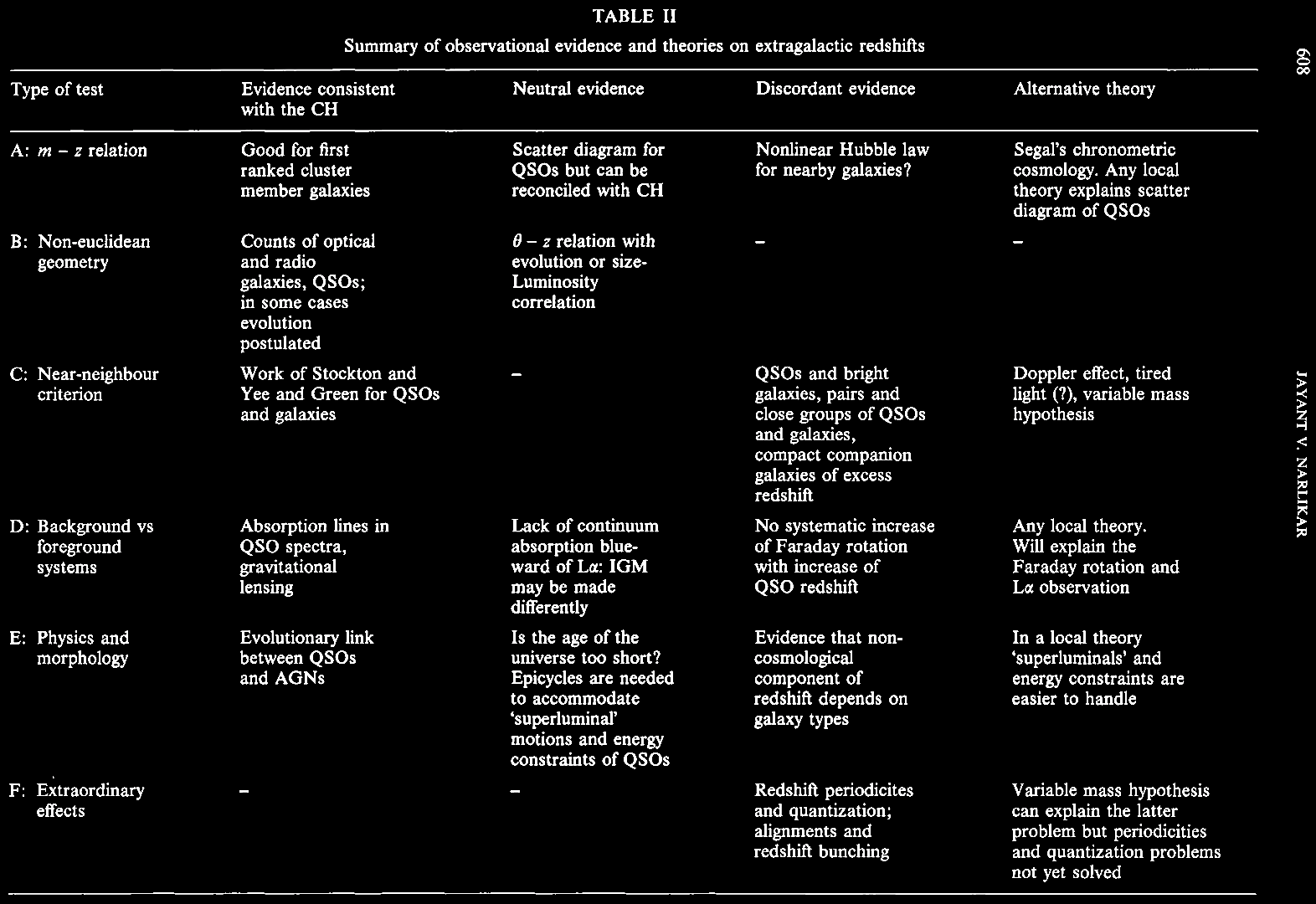

In 1989, Jayant Narlikar was invited to review the issue of 'noncosmological' or non-Hubble relation associated redshifts, and he also covered some of the hypotheses and a few theories put forward to explain these 'anomalous' data. Narlikar, J. V. 1989. Noncosmological redshifts (Invited Review). Sp. Sc. Rev. 50, 523. https://articles.adsabs.harvard.edu//full/1989SSRv...50..523N/0000538.000.html. Narlikar reviewed the history of the discovery of cosmological redshifts, which abide by the 'cosmological hypothesis' (CH) of an expanding Universe, as well as of the non-Hubble relation or 'anomalous' redshifts, and the attempts to interpret these data. Already multiple examples were known then (1989), and much more has been found since. We turn aside to consider this historic review from late in the 20th century. A forerunner of this review was a lecture given by Prof. Narlikar in 1986 at an IAU symposium, followed by a revealing discussion about how the subject was received at the meeting (Narlikar, J. V. 1986. Noncosmological Redshifts. Symposium - International Astronomical Union 119, 463-473; also In Swarup, G. & Kapahi, V. K. (eds.). Quasars, pp. 463-473. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0074180900153215).

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Then

about 2 decades, and now many decades, of data

collection show that QSOs do not have a linear

Hubble relation, but remain an anomalous scatter

diagram.  |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Now,

recognized as an unusually low value for the H0

constant in a sample of bright 3C galaxies. |

Non-CH

consistent clustering of redshifts around

certain periodic values.  |

|

|

|

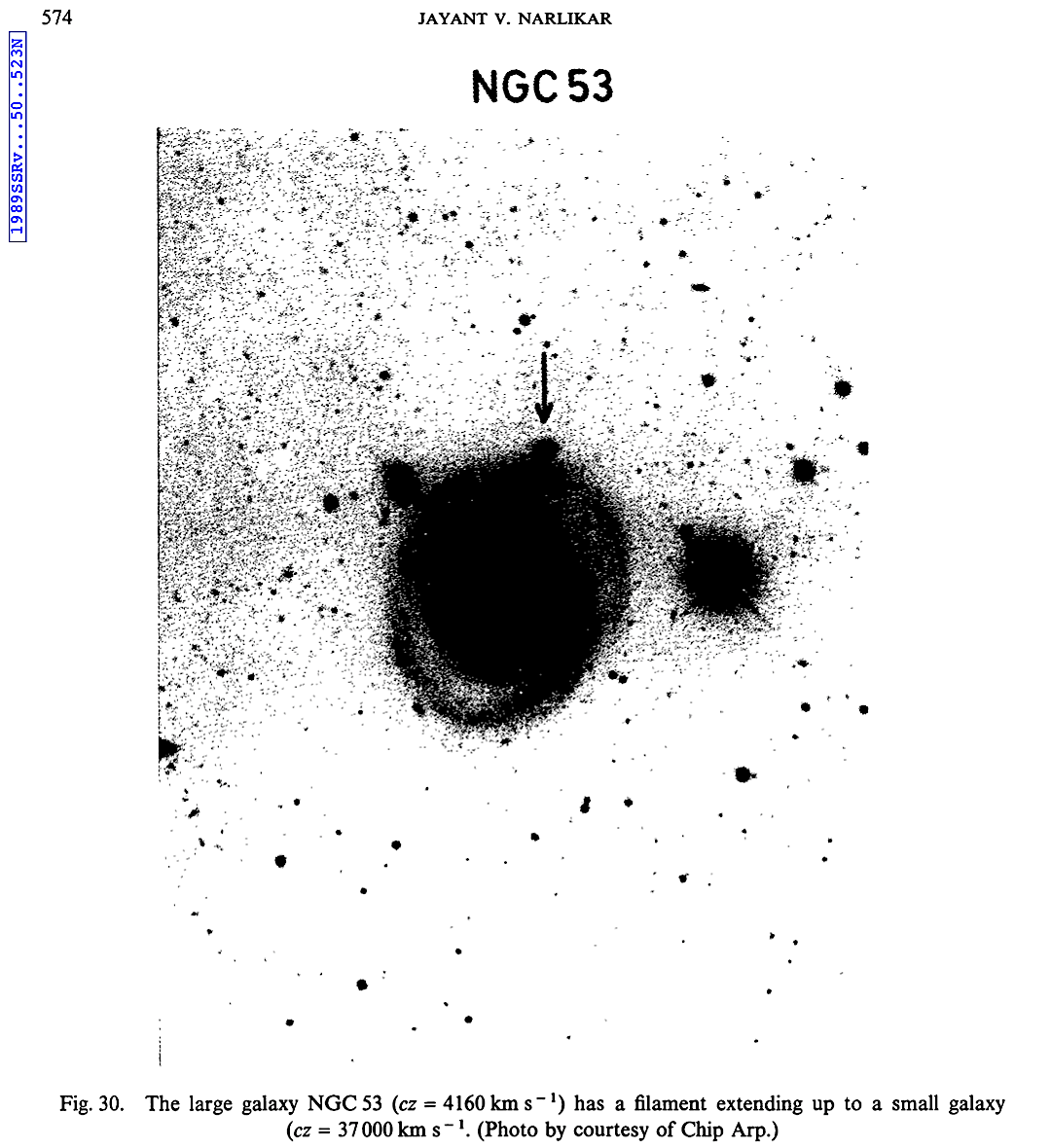

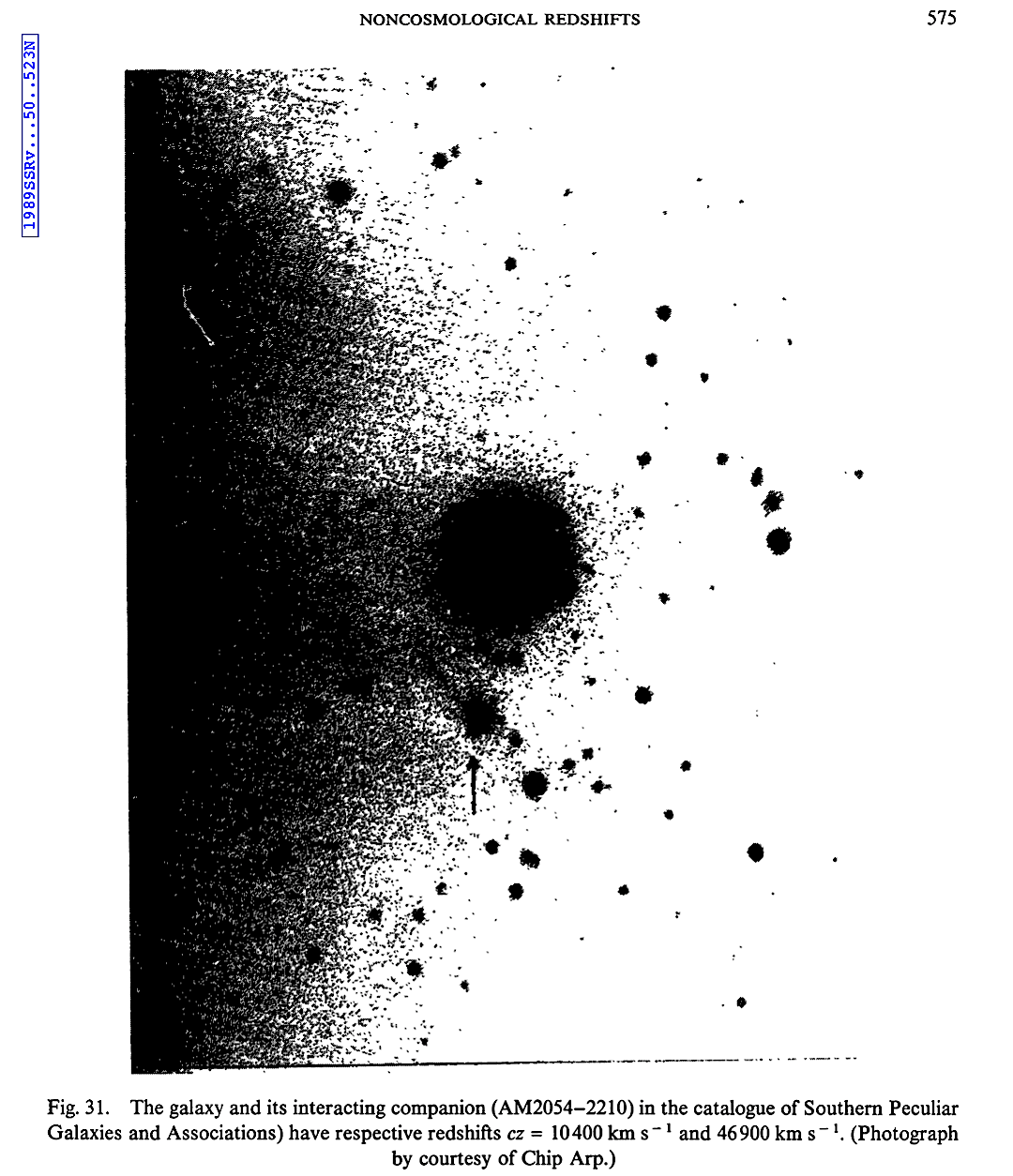

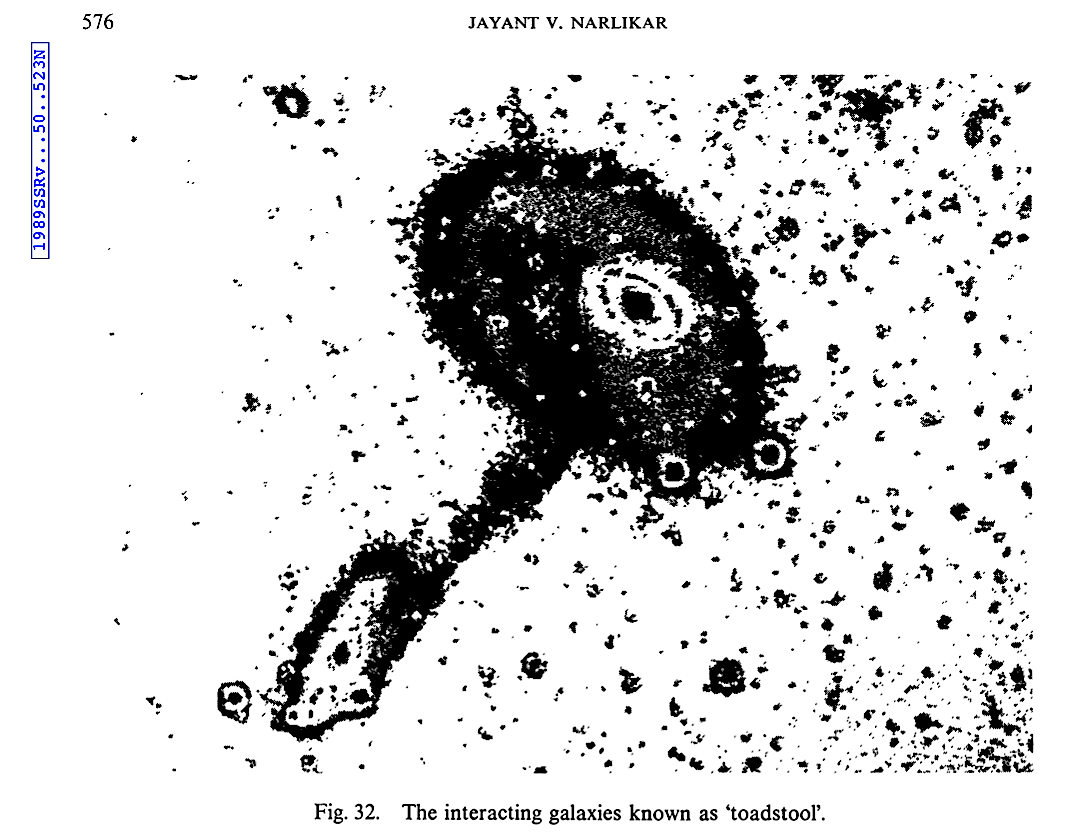

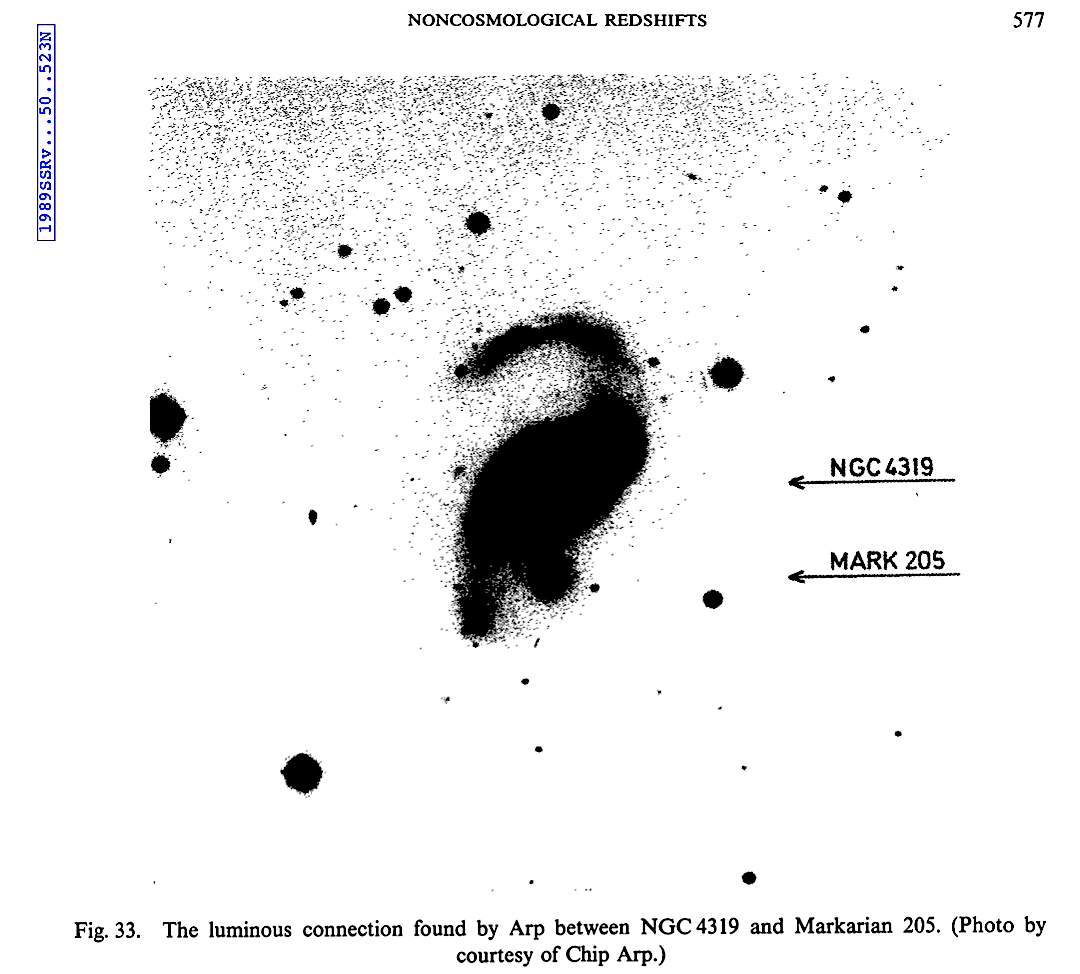

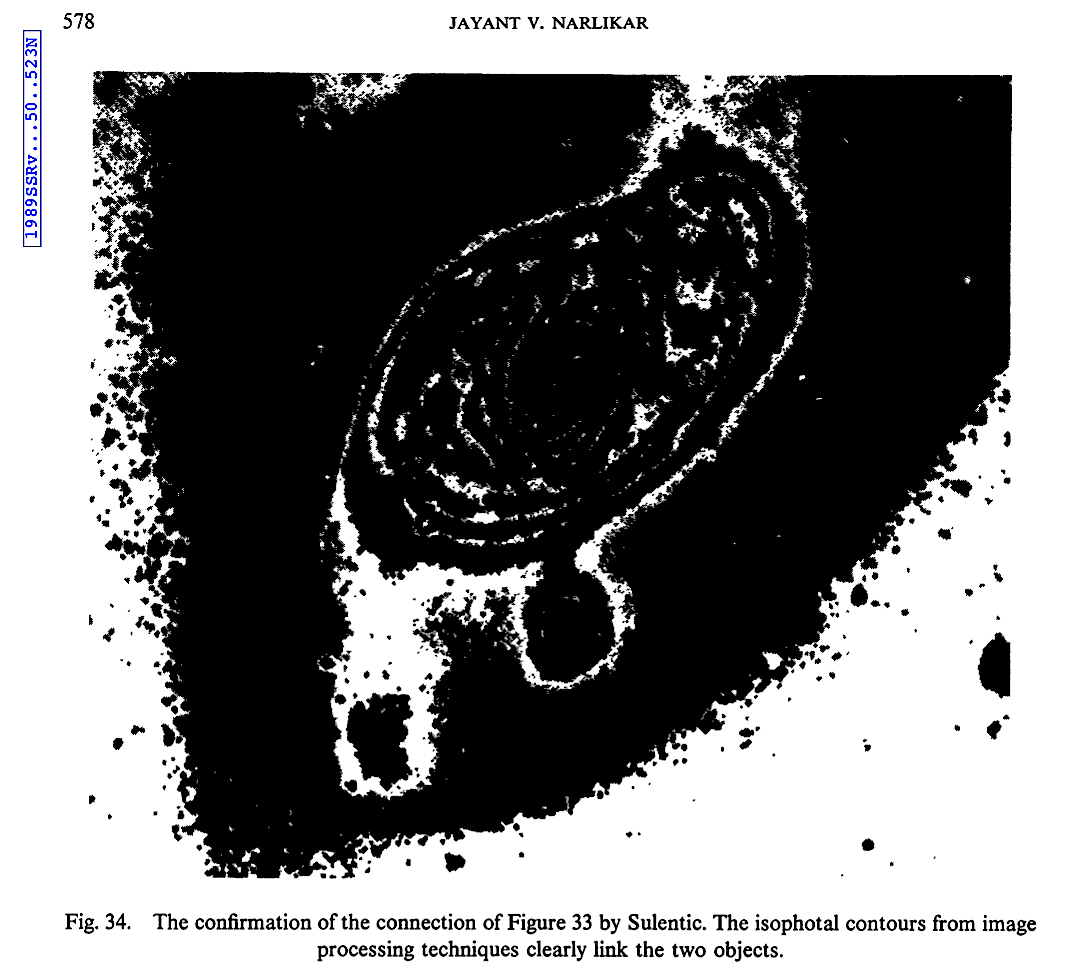

These

following images, cited in the review, are not

the astronomical images in their original

quality. For the original, higher quality

images, see the original publications cited in

Prof. Narlikar's review.  |

|

|

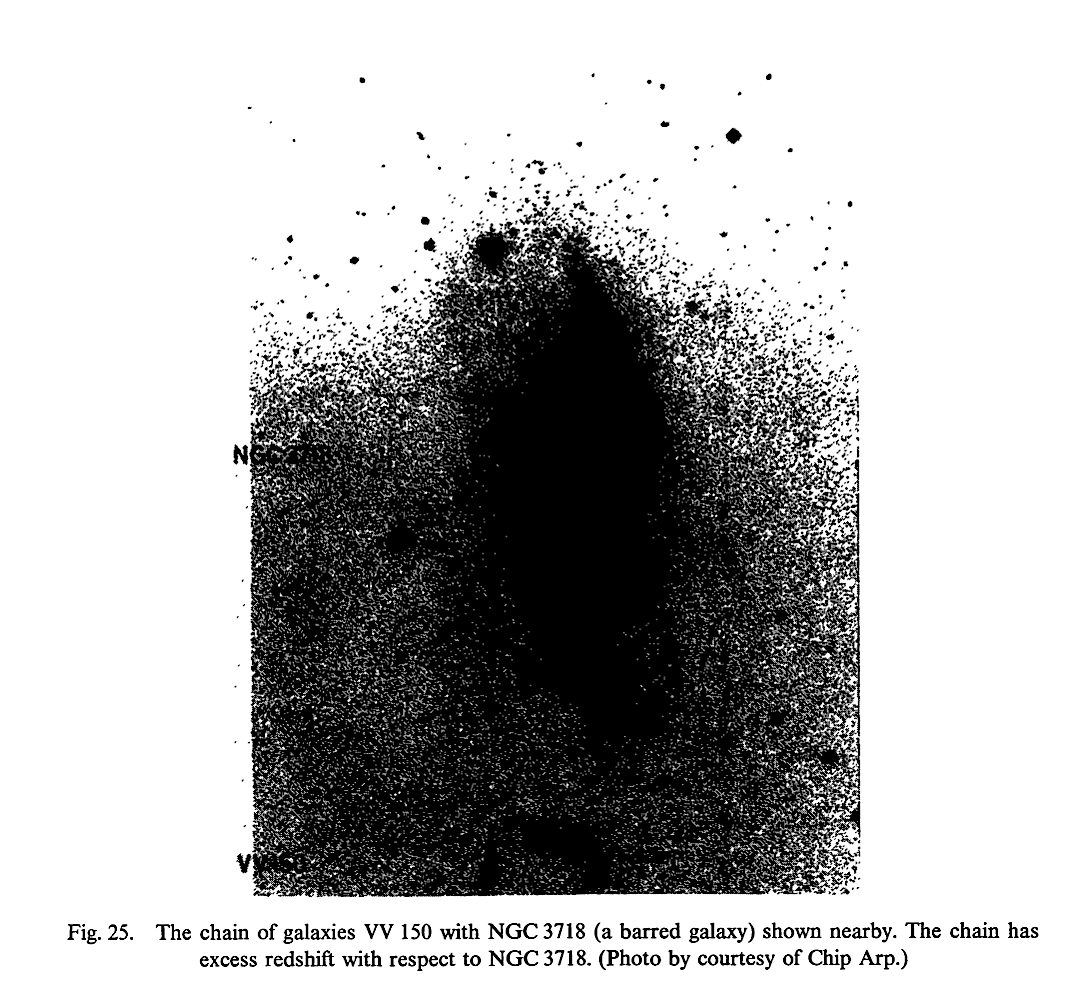

Companion

galaxies exhibit consistently higher redshifts

than the main galaxies in these groups. Under

the CH this should be more randomized.  |

|

|

|

|

|

|

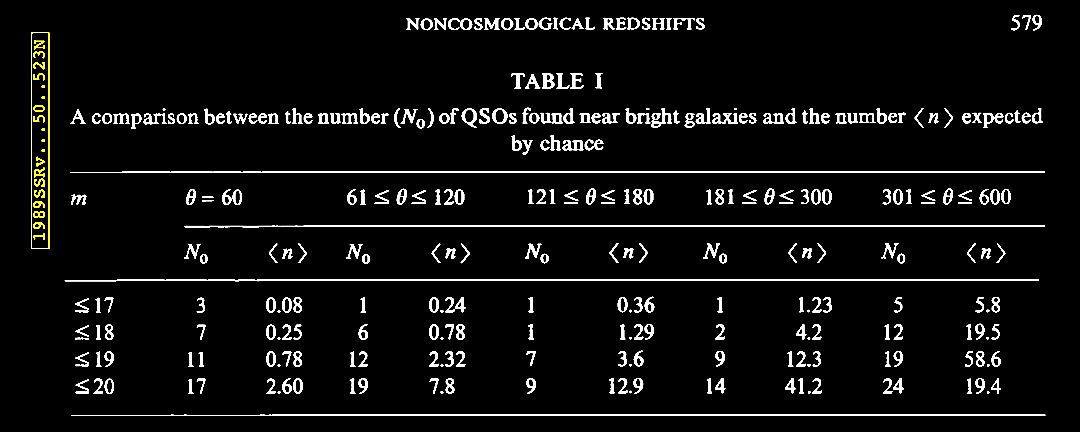

Under

the CH, QSOs should be randomly positioned in

the background, however they exhibit excess

clustering around near, bright galaxies.  |

|

Under

CH, there should be no such correlation. |

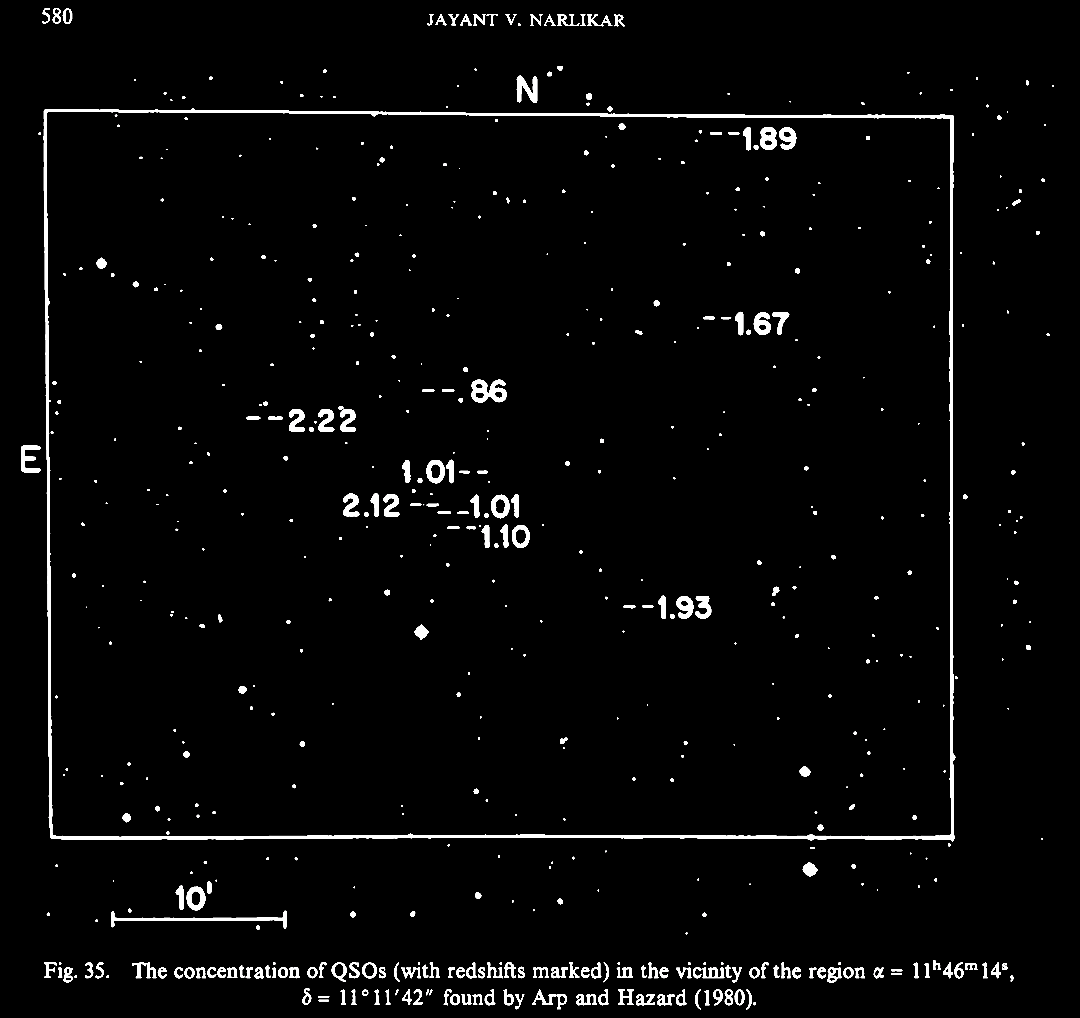

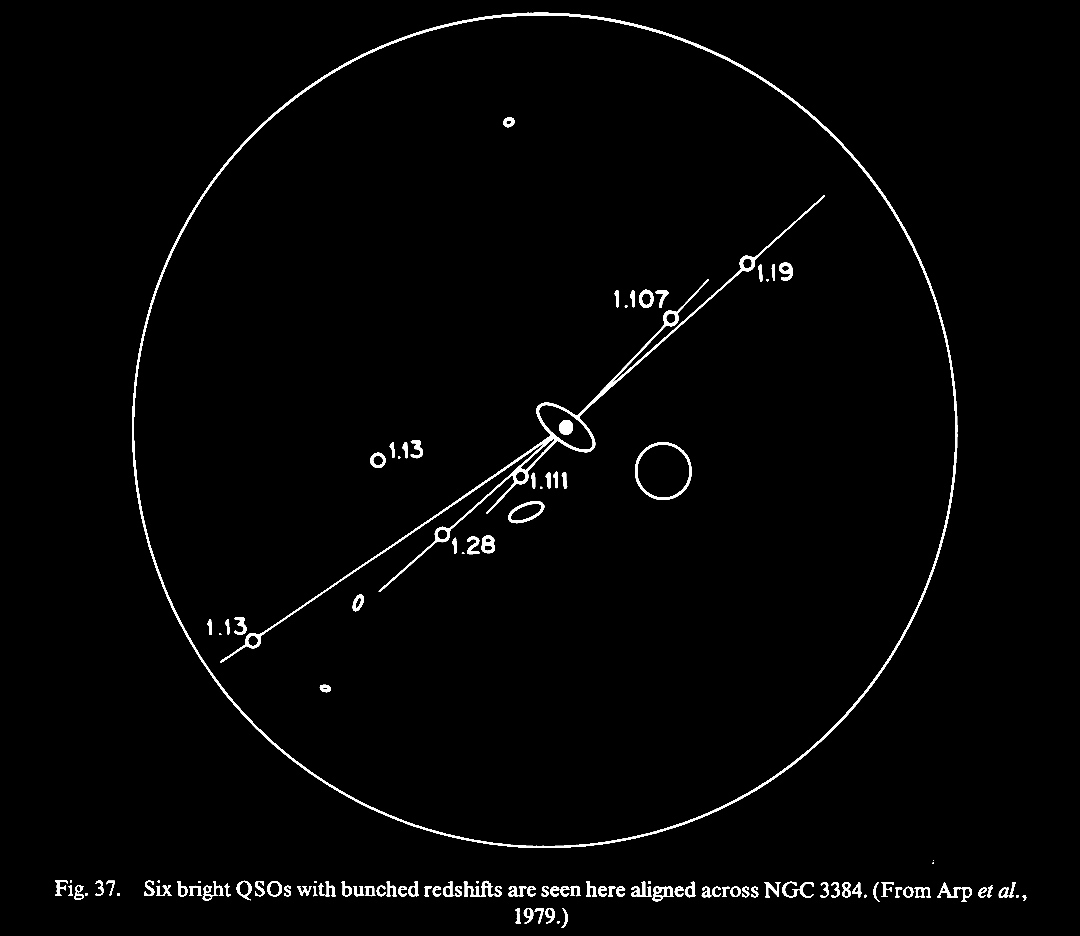

Juxtaposition

of higher redshift QSOs along the axis of NGC

3384, as if ejected along that axis. Under CH,

we would expect random background juxtaposition. |

Although

the quality of this image is poor, the three

QSOs are juxtaposed with the spiral arms, and

exhibit location of their z values at

Karlsson peaks.  See larger version above as well: (Arrows added to image from http://www.astronomy.com/asy/default.aspx?c=a&id=3430). |

|

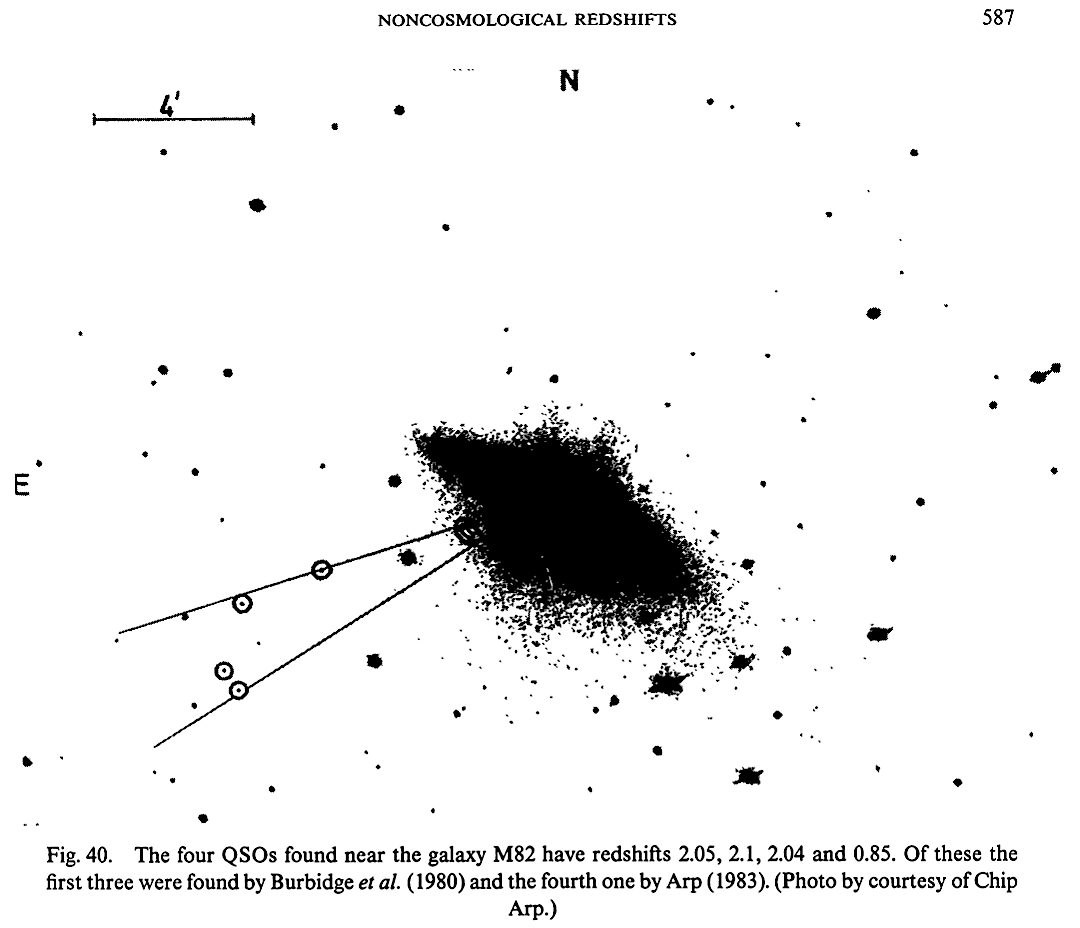

AGN

galaxy M82, we now know, not only has the 4

juxtaposed higher redshift QSOs but up to 15 as

discussed in chapter IX. Vast Jets,

juxtapositioning referenced in chapter V. JWST v ΛCDM. |

|

|

According

to the CH view of redshifts, these galaxies are

this discordant in size. |

Redshift

values weirdly in excess with certain galactic

morphologies, namly S0 and Sbc and Sc. |

|

In

the HN Machian gravity-cosmology, less massive

particles closer to their origin are more highly

redshifted. |

|

|

Narlikar (1989).

Narlikar (1989).We note that the empirical preferential clustering of redshifts around certain values began to be observed after 1970, and these were noted in the Narlikar review (1989) just cited.

Modified from figure 8-4 in H. Arp, 1998. Seeing

Red: Redshifts, Cosmology, and Academic Science.

Montreal, Quebec, Canada: Apeiron Press.

Representation of preferential clustering of redshift values (cited Arp, 1998) showing a preferential clustering around increments of 37.5 km s–1. In the case of QSOs / BSOs, a possible empirical relation which was pointed out early is 1 + z0 = (1 + zg)(1 + ze)(1 + zi), where z0 is the observed redshift, zg is the Doppler shift of the parent galaxy, ze is the QSO's Doppler shift (+ or -) from its putative ejection from the parent galaxy, and zi is an intrinsic redshift component-associated Machian age-mass scale in a matter creation process (Burbidge et al. 1999). That is one of the models of galactic cosmogony we will explore further.

Power spectrum of the redshifts of

97 spiral galaxies (Guthrie

& Napier, 1996; cit. in Hoyle et

al. 2000. A Different Approach to Cosmology: From

a Static Universe through the Big Bang Towards Reality.

Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press).

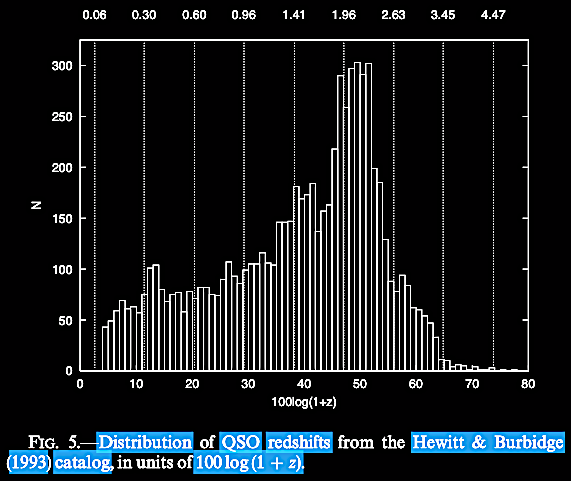

Frequencies of the redshifts of all

7315 then known QSOs with

peaks at z ~ 0.3, 1.4, 1.9-2.0. From Hoyle et al.

2000. A Different Approach to Cosmology: From a Static

Universe through the Big Bang Towards Reality.

Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press).

In 2003, a volume was published to

honor the late Sir Fred Hoyle (1915-2001) by C.

Wickramasinghe, G. Burbidge, & J. Narlikar. (eds.). 2003. Fred Hoyle's Universe. Dordrecht, The

Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers, with lots of

invited scientists, astronomers, and astrophysicists, on

subjects as varied as Hoyle's contributions to people's

personal reminiscences, stellar structures and

evolution, cosmology, interstellar matter, and

panspermia. Among the chapters, two were

devoted to redshift periodicities: W. M. Napier on p. 139,

republished from A statistical evaluation of anomalous

redshifts. Astrophysics and Space Science 285

(2), 419.

https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1025452813441.

The

hypotheses Napier tested statistically were observations in

the light of so-called class of 'anomalous' redshifts for

pairs of galaxies and QSOs with widely different z-values,

often displaying bridges of luminosity between them. These tests are

critical tests of the universality of the Hubble distance

relation and whether the HBBC fails the test.

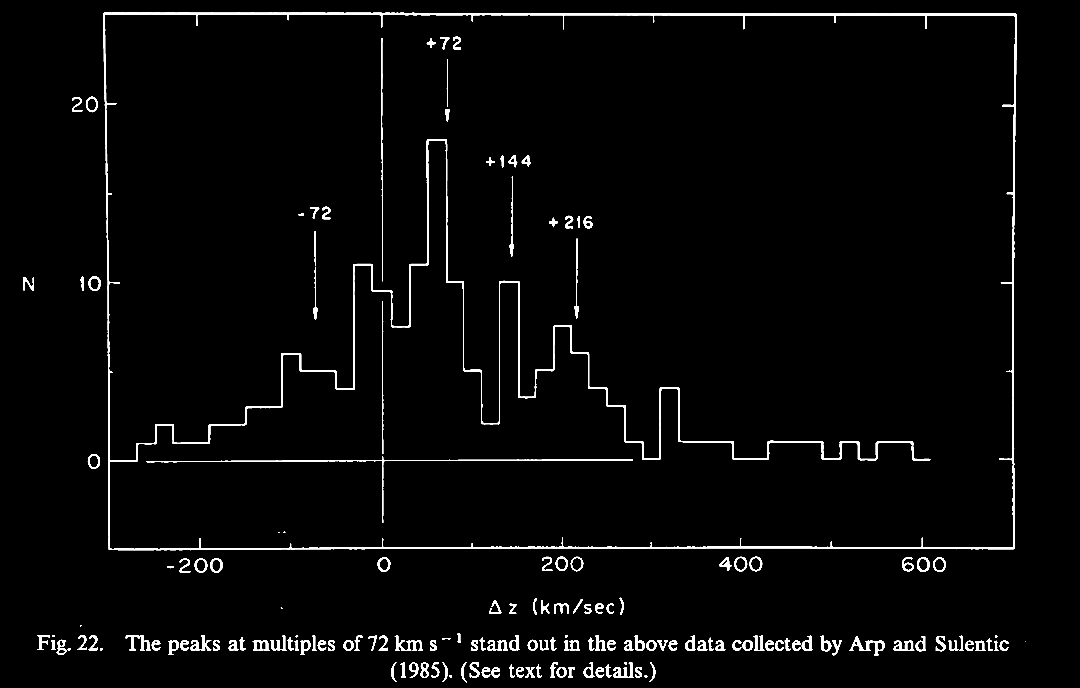

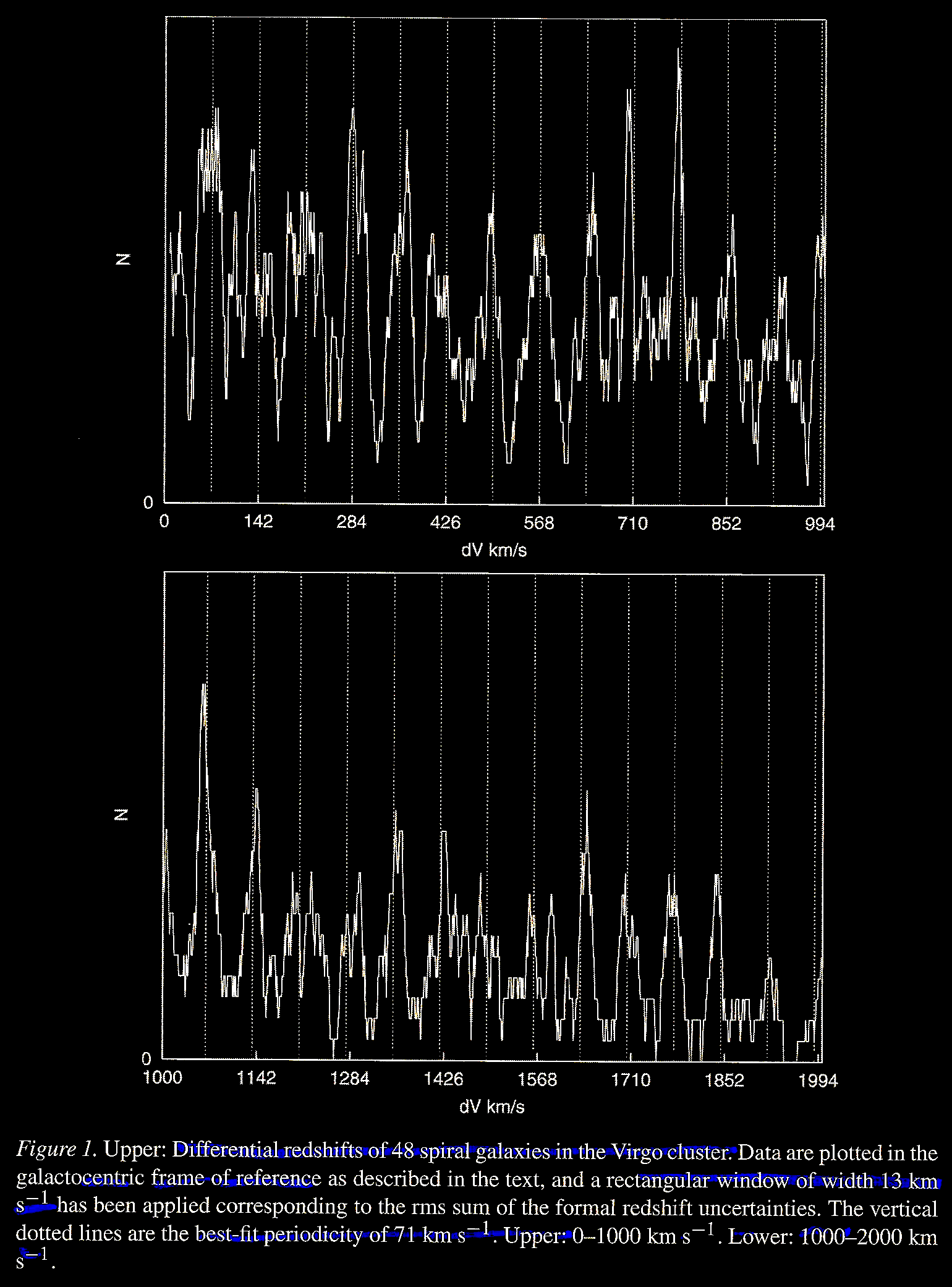

(a)

The first claim was that in the galactocentric frame of

reference, the Virgo cluster spiral galaxies have a

distribution with a periodicity of 71 km s–1,

which is similar to an early claim of 72 km s–1

in the Coma cluster of galaxies by

Tifft, W. C. 1976. Discrete states of

redshift and galaxy dynamics. I.

Internal motions in single galaxies. ApJ

206, 308. https://ui.adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/1976.

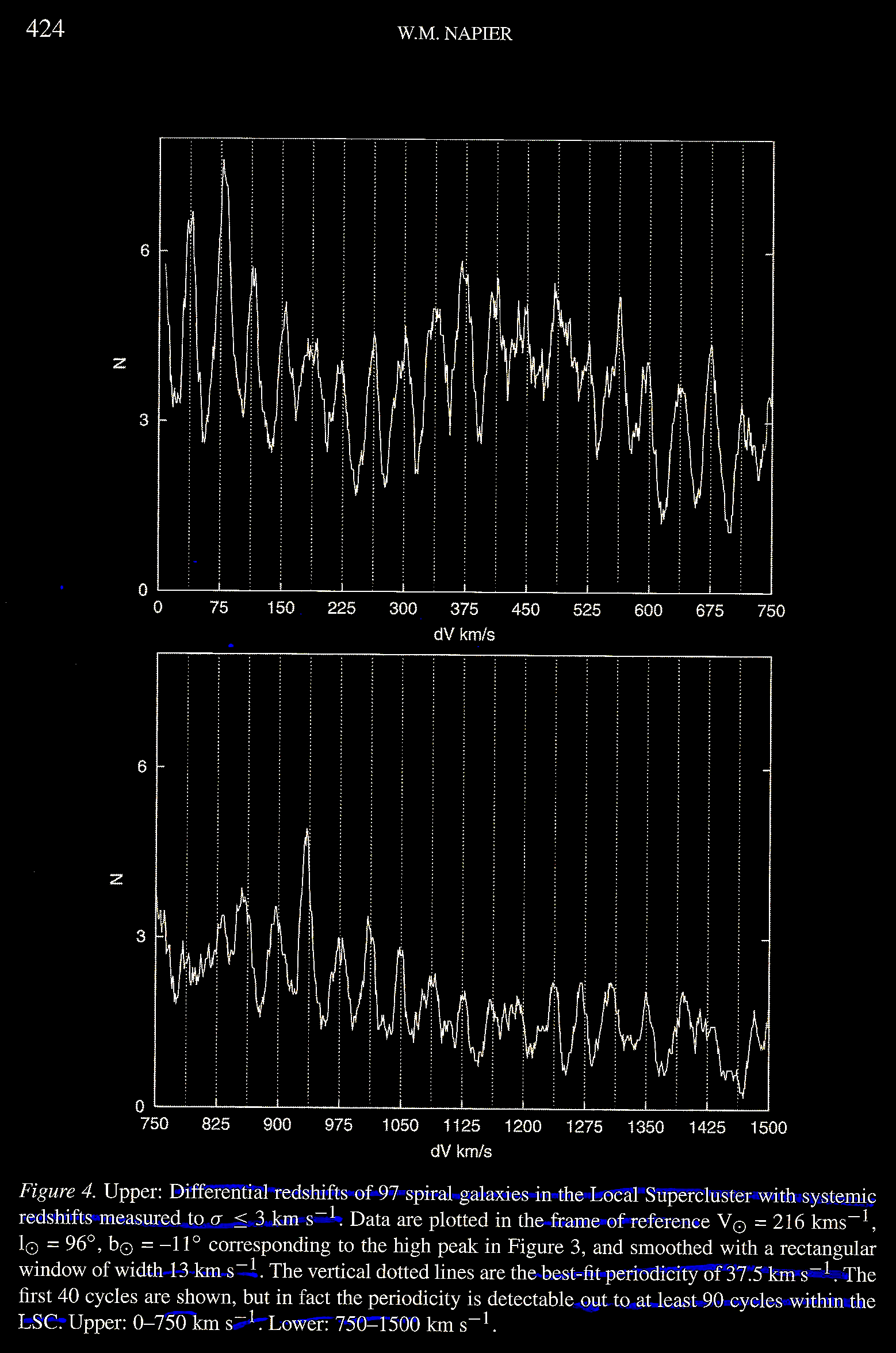

Napier (2003) figure 1 shows part of the

periodicty / redshift frequency data.

The significance of

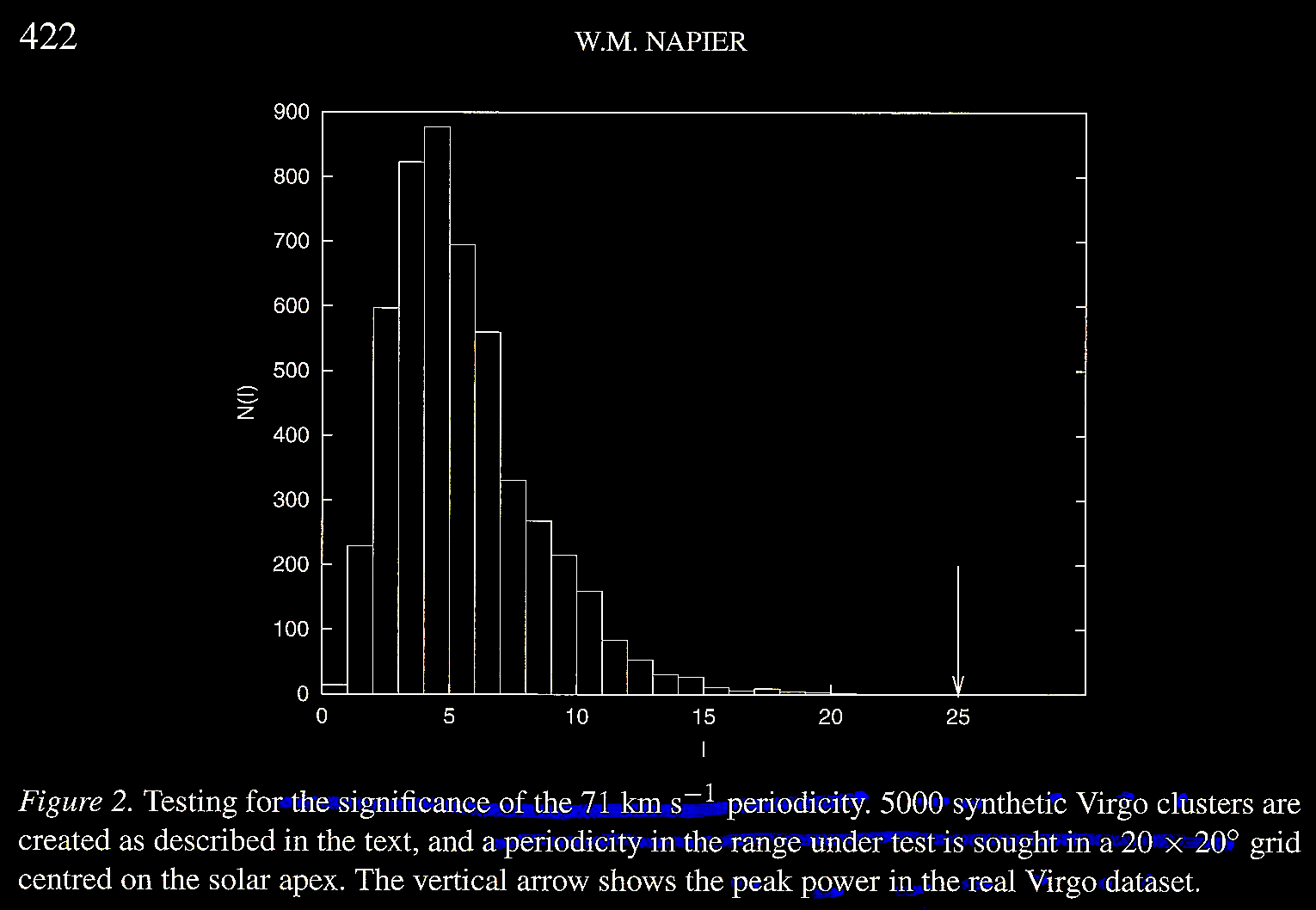

the 71 km s–1,

periodicity was determined by synthetic

simulations of Virgo clusters. The statistical

tests were searches of 3-d spaces to find a

single Imax, that is, the

highest power to be found anywhere in the

parameter space of the study. The test results

for the real data set of the actual Virgo

Cluster are very robust indeed (Napier, 2003;

Figure 2).

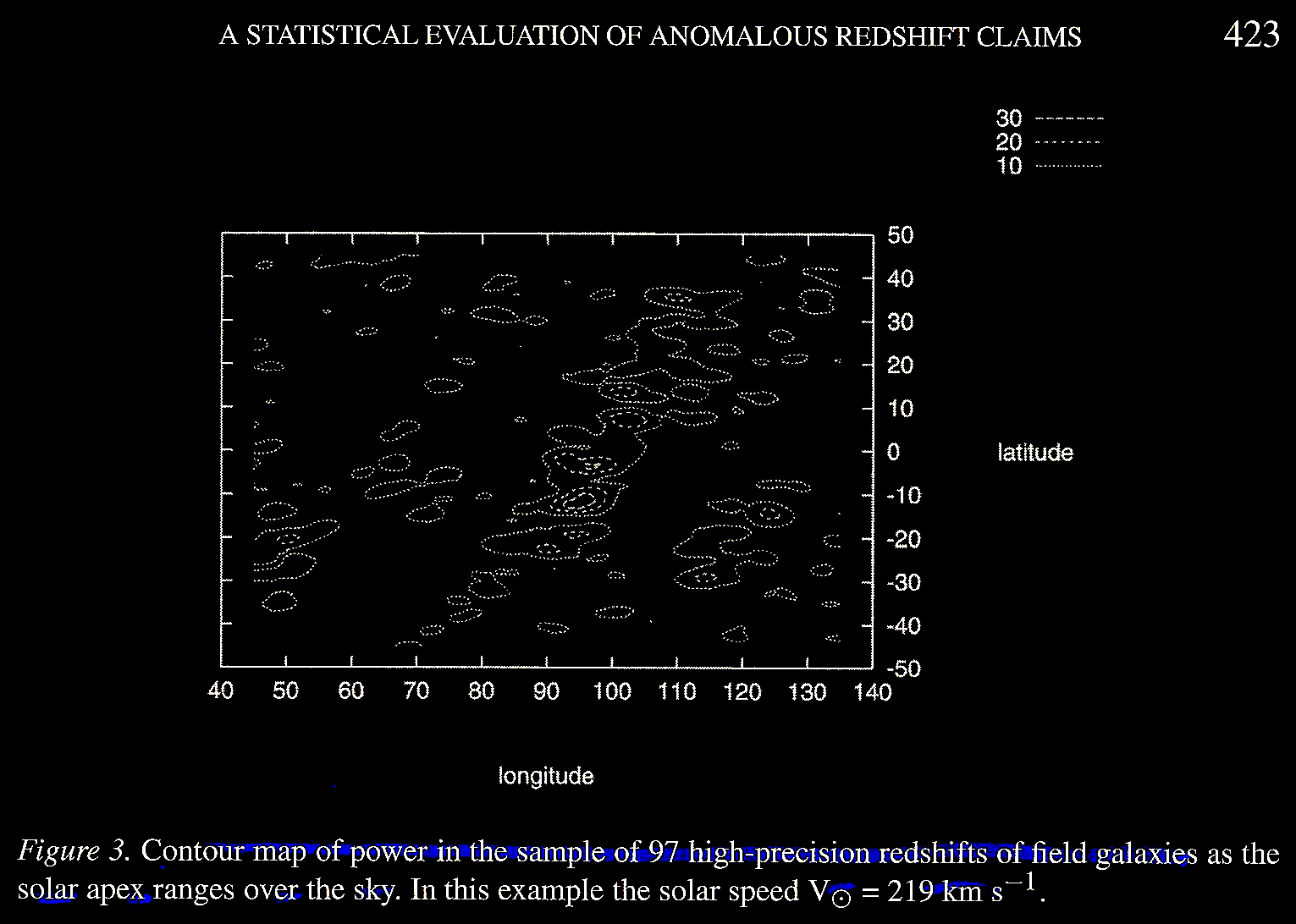

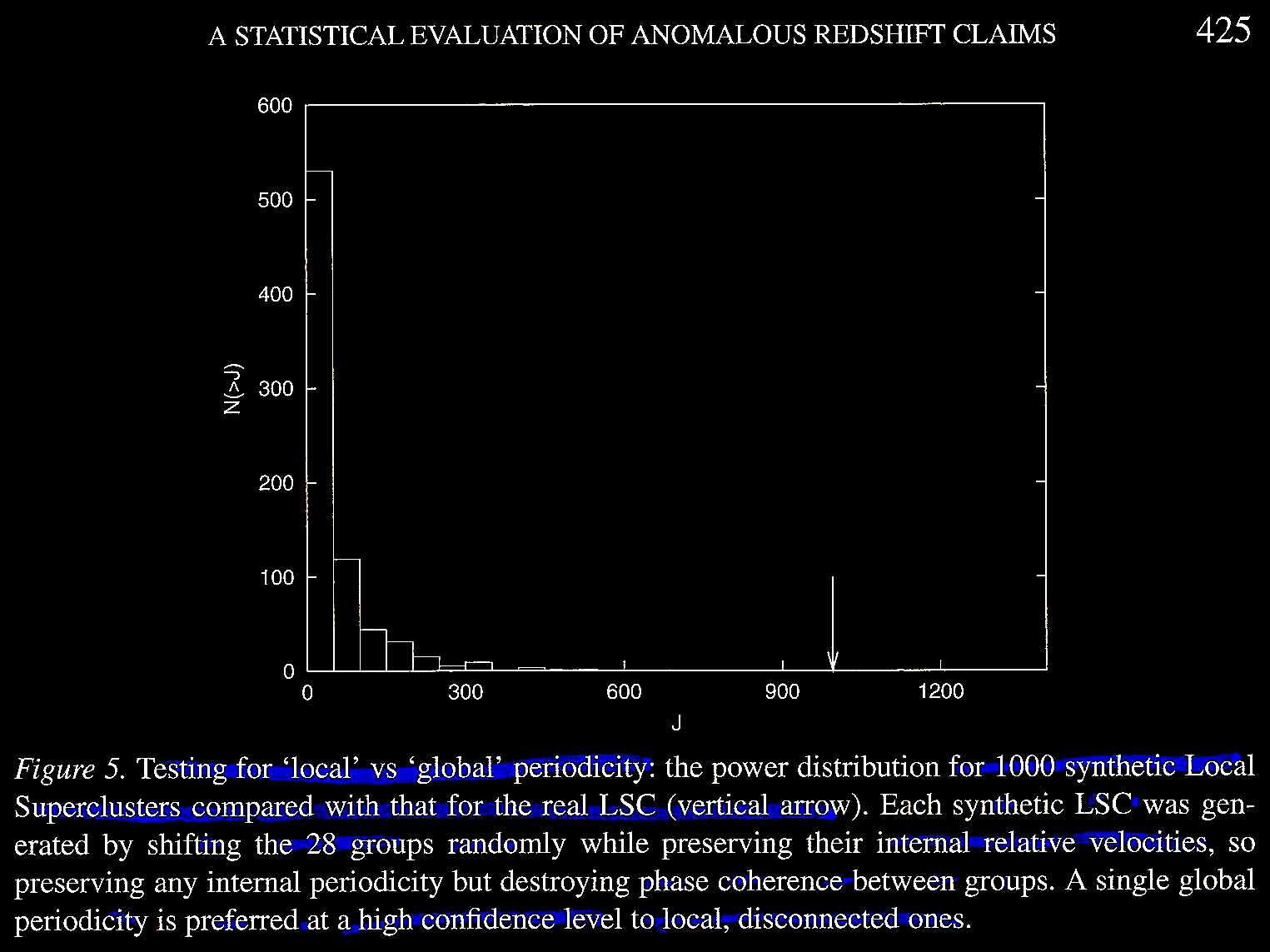

(b) The second claim was that

there is a galactocentric periodicity among

"wide-profile field [spiral] galaxies" of 36 km s–1

in the Local Super Cluster (LSC) as reported by Tifft

& Cocke. 1984. Properties of the redshift. ApJ

287, 492. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0252921100005546.

Napier's more accurate tests showed a 37.5 km s–1 periodicity in the LSC, as

portrayed in Napier, Fig. 3.

And in Figure 4,

which shows a persisting and robust 37.5 km s–1

periodicity out to 40 cycles, but detectable out to at least

90 cycles, Napier found. This is shown by Arp in 1998 as

indicated above, including by a power spectrum test (see

figure cited by Hoyle et al. 2000 on the power

spectrum of a periodicity of 37.6 km s–1).

As Tifft and Cocke (1984) had

suggested, a robust 37.5 km s–1 redshift

periodicity, in a galactocentric frame of reference, has

been found within the Local Super Cluster (LSC). A J

statistical test with simulations for artificial LSCs

was used to test whether the periodicity is a local or a

global effect.

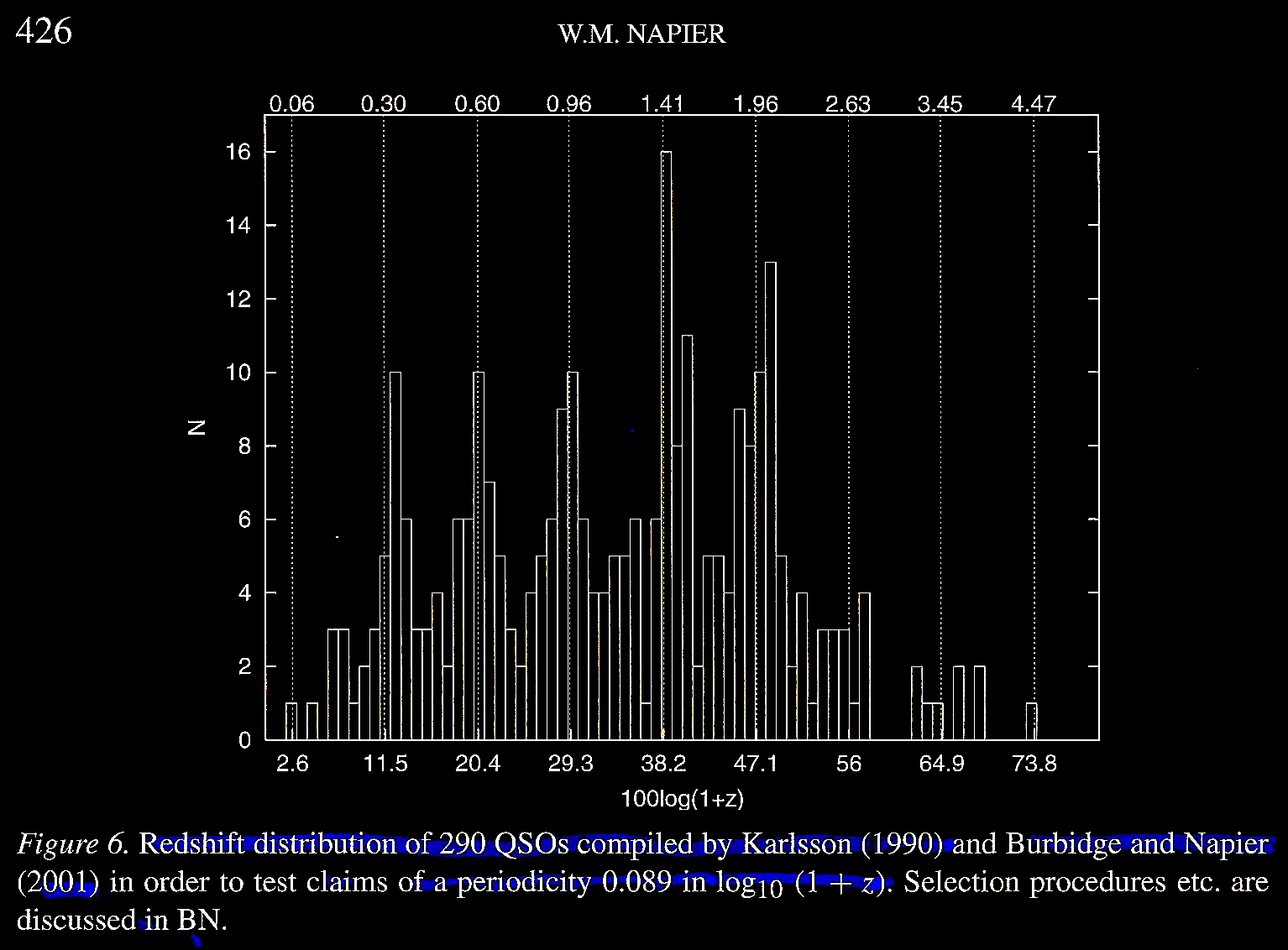

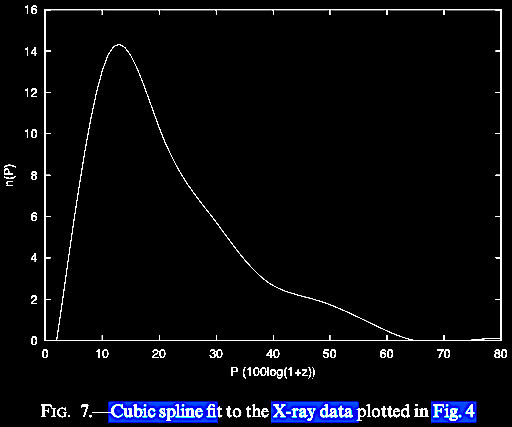

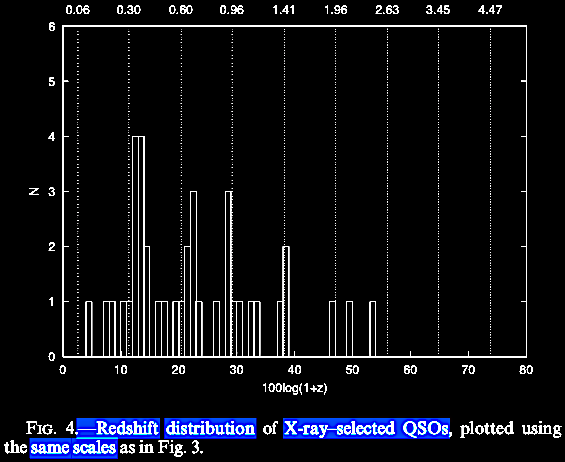

(c) The third claim was that quasars or QSOs clustered around bright local galaxies exhibit a redshift periodicity of 0.89 in log10 (1 + z), although it is not clear whether this is within the galactocentric frame of reference or local periodicities from discrete velocity residuals with respect to the variable solar apex used in assessing the periodicity found in the study of the Virgo Cluster done by Guthrie, B. N. G. & Napier, W. M. 1991. Evidence for redshift periodicity in nearby field galaxies, MNRAS 253 (3), 533. https://doi.org/10.1093/mnras/253.3.533. See also Napier, 1999. Quantized redshifts - New physics or old muddle? Symposium - International Astronomical Union, Volume 194: Activity in Galaxies and Related Phenomena, pp. 290-294. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0074180900162126. What they found was that there is indeed such a periodicity in the distribution of the QSOs appearing around local galaxies.

The

work of Karlsson (1990. Astronom. Astrophys. 239,

50) and and that of Burbidge & Napier, 2001; The

distribution of redshifts in new samples of quasi-stellar

objects. Astrophys. J. 121 (1), 21. https://doi.org/10.1086/318018,

was confirmed.

Napier concluded that if all of the above periodicities (a), (b),and (c) are real, then they must be the effects of some single underlying phenomenon and must be connected with the linearity of the local Hubble flow. Again, a cosmology other than the standard HBBC was indicated. We will return to this Burbidge & Napier (2001) paper below, after discussion of Tifft's modeling.

Another paper from the same memorial

volume for Fred Hoyle was Tifft, W. 2003. Redshift

periodicities, the galaxy-quasar connection. Astrophysics

and Space Science 285 (2), 429. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1025457030279.

This paper develops the consequences of a particular

decay model for predicting the periodicities in redshift

found in various data sets, including the Hubbled Deep

Field (HDF) and Hubble Southern Deep Field (SDF),

tackling three classes of observations of intrinsic

redshifts departing from the linear Hubble redshift

relation, (α) characteristic peaks in QSO redshift

distributions, (β) associated objects with very

discordant redshifts, and (γ) normal galaxy redshift

quantization.

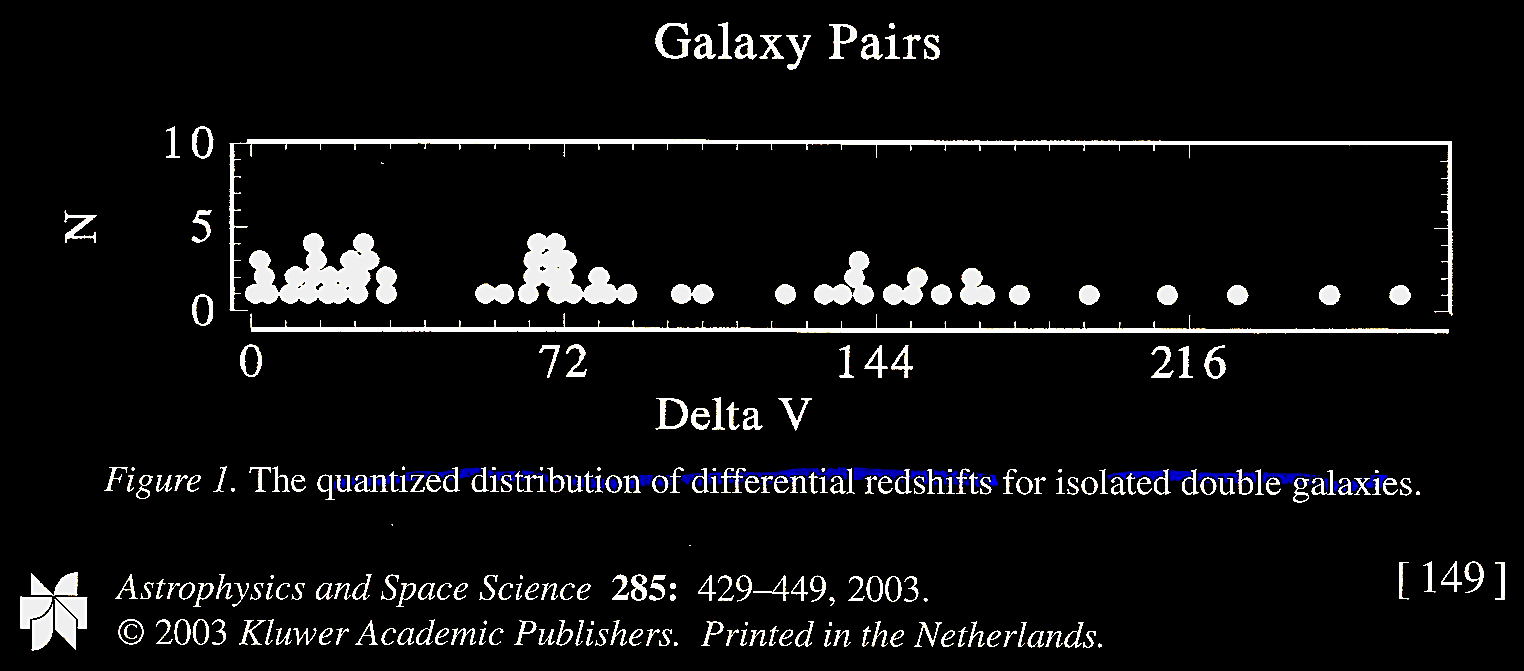

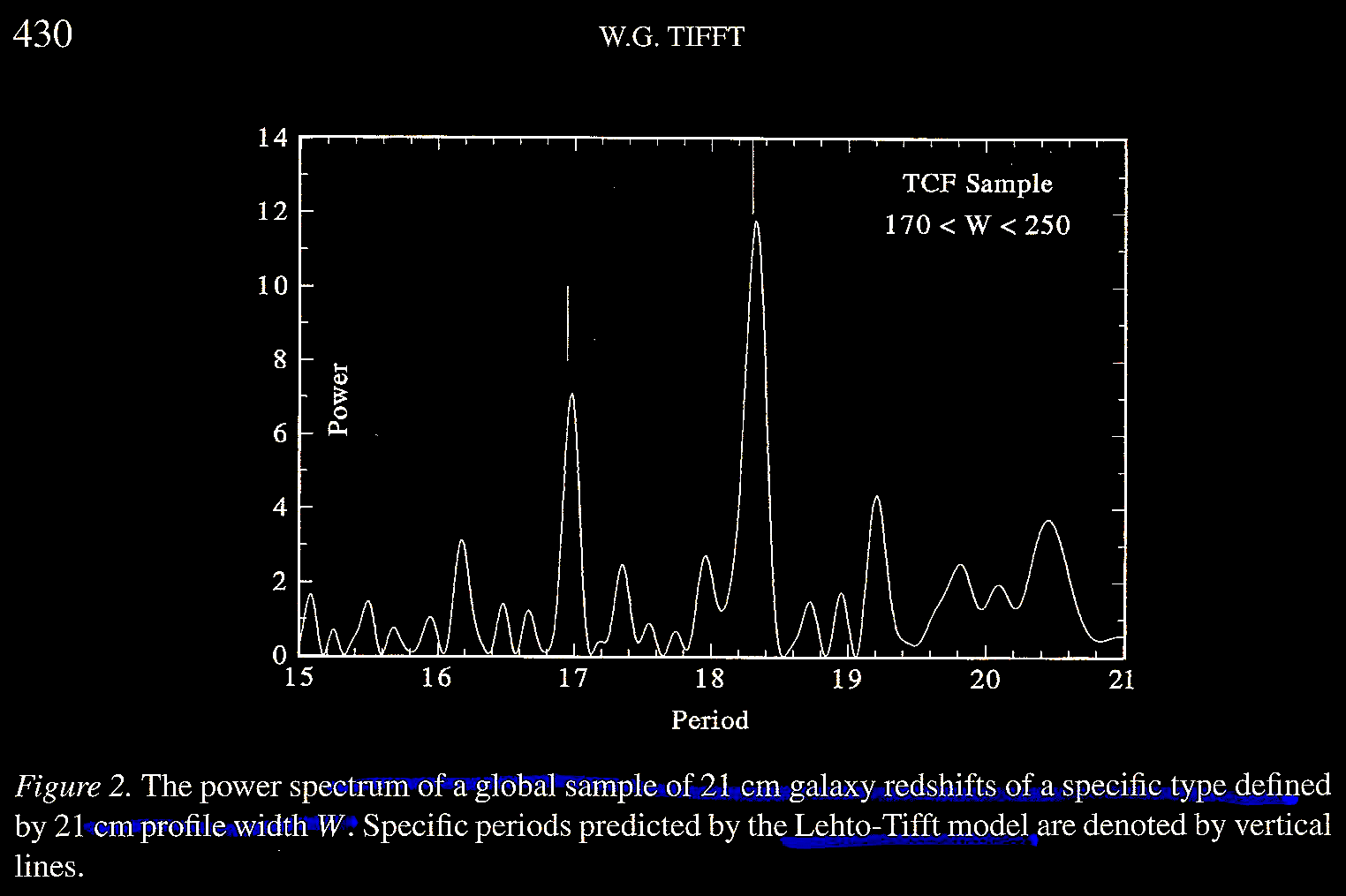

Tifft

(2003) Figure 1 illustrates the periodic quantized redshift

distribution for double glaxies (Tifft & Cocke, 1989).

Figure 2 shows the characteristic redshift

periods observed globally using concepts which predict the

discrete values (Tifft, 1996).

A first principles Planck

decay process & the Lehto-Tifft quantization model

equations. Although previous work (before 1992)

had focused on empirical periodic intervals observed

differentially or globally in a galactocentric frame of

reference, the emphasis shifted thereafter to the cosmic

background frame of reference. Finnish physicist Ari

Lehto put forward a mechanism for predicting

redshift periodicities (1990. Chinese J. Phys. 28,

15), which Tifft (1996; 1997) tested, confirmed, and

developed into the Lehto-Tifft quantization model with a

set of equations: Tifft, W. G. 1996. Global redshift

periodicities and periodicity structure. ApJ 468,

491. http://dx.doi.org/10.1086/177710;

and Tifft, 1997. Global redshift periodicities and

variablility. ApJ 485, 465. https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.1086/304443.

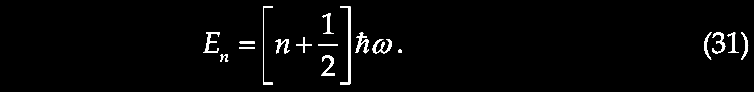

In what follows, we closely follow Tifft (2003):

Lehto

(1990) planned to describe fundamental particle properties

using first principles, namely beginning with the original

Planck units of Max himself (link),

listed here with their modern values all calculated using 3

fundamental constants in modern values, the velocity of

light in vacuo, or c = 2.99792458 x 108

m s–1

(link),

the reduced (divided by 2π, i.e., it's Dirac formulation)

Planck constant ħ = 6.582119569 x 10–16

eV⋅s (link),

and the gravitational constant G = 6.674 x 10–11 m3⋅kg–1⋅s–2 (link):

- the Planck

time (T) = 5.391247(60) x 10–44 s,

- the Planck

length (L) = 1.616255(18) x 10–35 m,

- the Planck

mass (M) = 2.176434(24) x 10–8 kg,

- and the

Planck temperature (Θ) = 1.416784(16) x 1032

K, as well as we should add

for reasons later to be apparent,

- the coherently derived Planck unit of the Planck energy (L2MT–2) = 1.2209 x 1019 eV, converted from joules to electron volts, also for reasons later to be apparent.

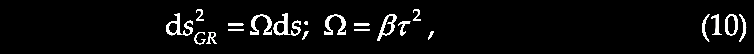

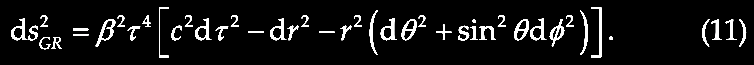

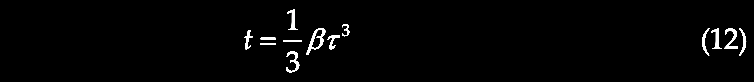

where N is an integer ≥ 0. In applying this to particle physics, we replace c with the Planck mass (M) or energy (L2MT-2). The above equation is significant in being a general form comparable to Kepler's Third Law in ordinary space, where "a spatial distance relates to the 2/3 power of a time interval,... a unique property of 3-d spaces." This suggests "the possibility that temporal/frequency/energy space is actually 3-dimensional." If such a "3-d temporal space" flows relative to a "3-d spatial space" then the constancy of c and the applicability of special relativity are preserved. "Temporal space" is quantized into a stepwise decay process from the fixed units indicated. In a dynamic 4-space with 3-space and flowing 1-time, there are no such restrictions, so according to Tifft (2003), quantum physics and continuous, infinitesimal classical physics can co-exist.

At this point, Tifft argued that one may re-write equation (1) to distinguish cube-root doubling families thus

where D is the number of doublings and L = 0, 1, 2 to specify which root is utilized. Tifft (2003) points out that equation (2) predicts most redshift periodicities, however to account for all of the observed periodicities, one needs a second cube root to produce 9 9th-root famliies distinguished by a n index T:

Equation

(3), claims Tifft (2003), "completely and uniquely

describes" all of the periodicities observed as of Tifft

(1996, 1997). The index T values are not random, but

involve pure doubling, T = L = 0, the

dominant relation, followed by a 'Keplerian' T = 6 (L

= 2) value, where the odd T values are shifted by 1

as in T = 1, 5, 7 which is less common, and

finally the even values of T = 2, 4, 8 are rare or

absent entirely. Weirdly, which T family is observed

seems to relate to galaxy morphology (Tifft, 1997). Equation

(3) seems to describe redshift distributions in local

galaxies, whereas at higher redshifts and deeper in space,

the T = 0 family "becomes increasingly dominant."

A

correction must be made to assess underlying redshift

quantization, and that is, redshift intervals "dilate with

distance" because of effects both relativistic and

geometric, which must be removed. Classically in cosmology,

'curvature' is described by the 'deceleration' parameter q0,

while the Hubble 'constant' serves as a function of time, H

= H(t) = f(z, q0),

which in a flat or Euclidean cosmos would have q0

= 1/2. Removing the z-dependent distortion

is called the 'cosmological' correction in redshift. Tifft

& Cocke (1984) investigated the 'cosmological'

correction for global redshift quantization studies. Tifft

(1996) assumed that redshift intervals dilate as √[H(t)]

to show a linearization of galaxy redshifts out to

>10,000 km s–1 provided that q0

= 1/2. Tifft (2003), whose treatment we are following,

showed that this correction works well out to z = 1

or 2, far enough to encompass, as we shall see, the Hubble

Deep Fields North and South, taken in the 1990s. Following

the classical H(t) formulation to find the

function H(t)

= f(z, q0), Tifft

integrated with a Taylor expansion around q0 =

1/2 to arrive at a closed relation between z(observed)

and z(Lehto-Tifft):

(4)

zobs = {[z(LT)/4]

+ 1}4 – 1

z(LT) = 4[(1 + zobs]1/4

– 1,

a formulation

empirically-fitting all of the then available data (Tifft,

1996, 1997). Tifft (2003) uses equation (4) to convert

observed redshift to z(LT)

to evaluate redshift quantization. Since equation

(4) is consistent with the "temporal 3-d space"

model discussed above, where energies vary with

temporal volumes as t3 so that

if photon redshifts are a result of energy

densities, which vary as these volumes evolve, the

rate of change will be observed as H = H(t) = f(z,

q0).

The spatial volume will evolve as t2 so

that H = H(t) = f(z,

q0)

depends on t2

redshift periodicities vary as √[H(t)]

exactly as observed.

At this point, let's look at the

data which Tifft (2003) summarized in light

of the doubling decay process postulated in

the Lehto-Tifft model:

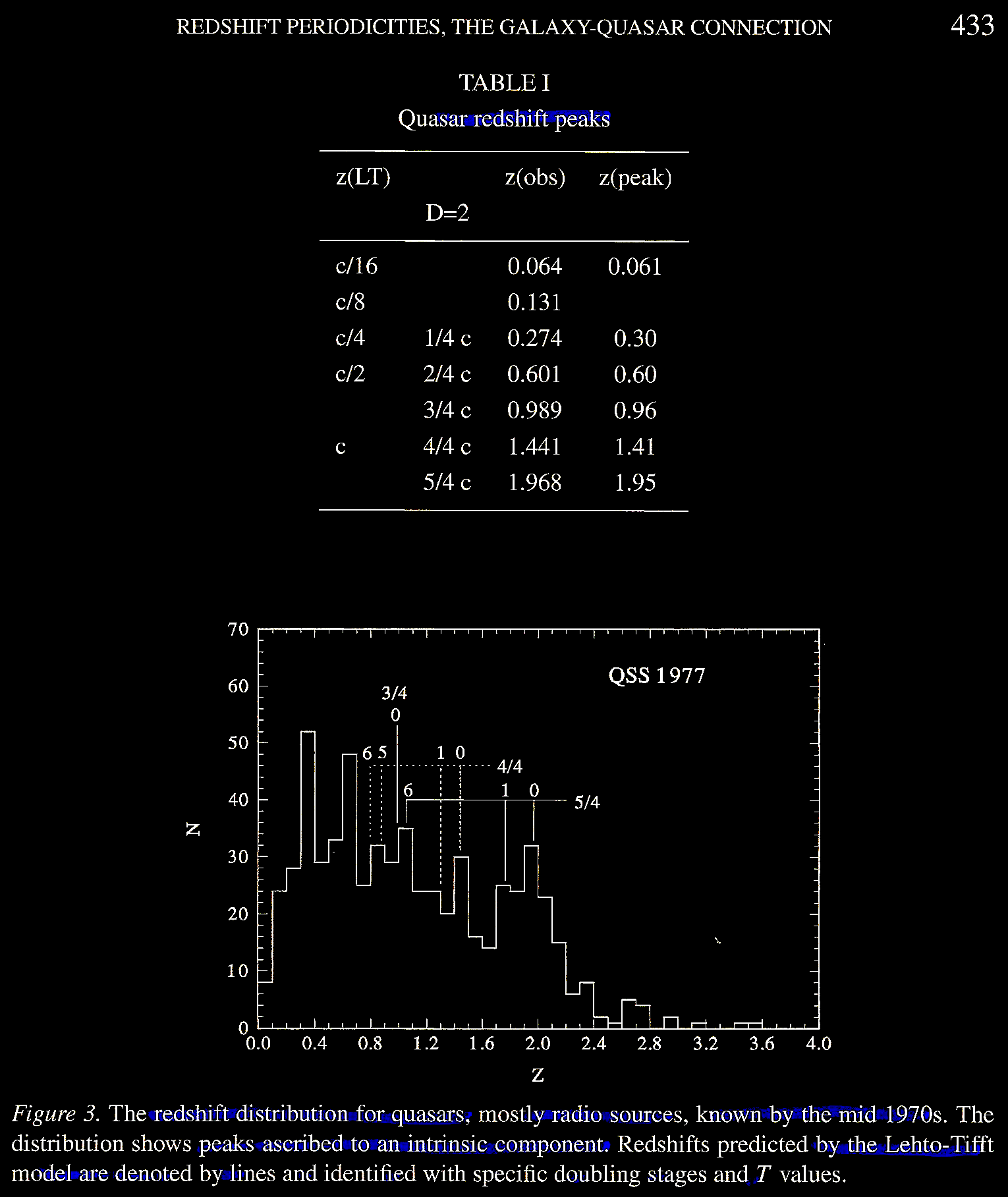

Tifft's (2003) Table 1 shows that

the redshift peak locations match the

empirical logarithmic sequence of QSO

redshift peaks observed by Karlsson, K. G.

1977. On the existence of significant peaks

in the quasar redshift distribution. A&A

58 (1,2), 237. https://articles.adsabs.harvard.edu//full/1977.

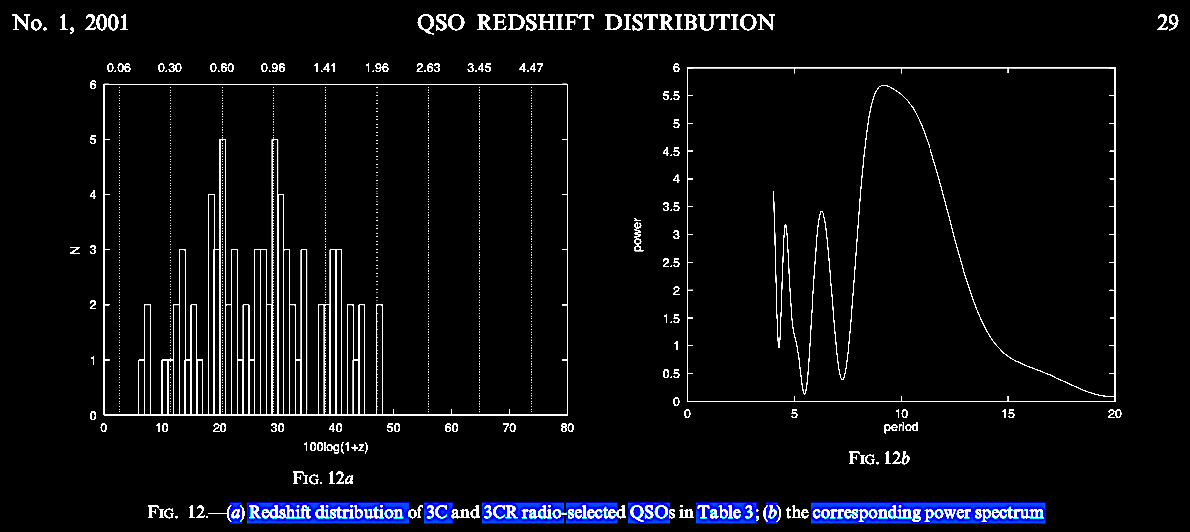

Tifft (2003) Figure 3 shows the quasars

known in 1977.

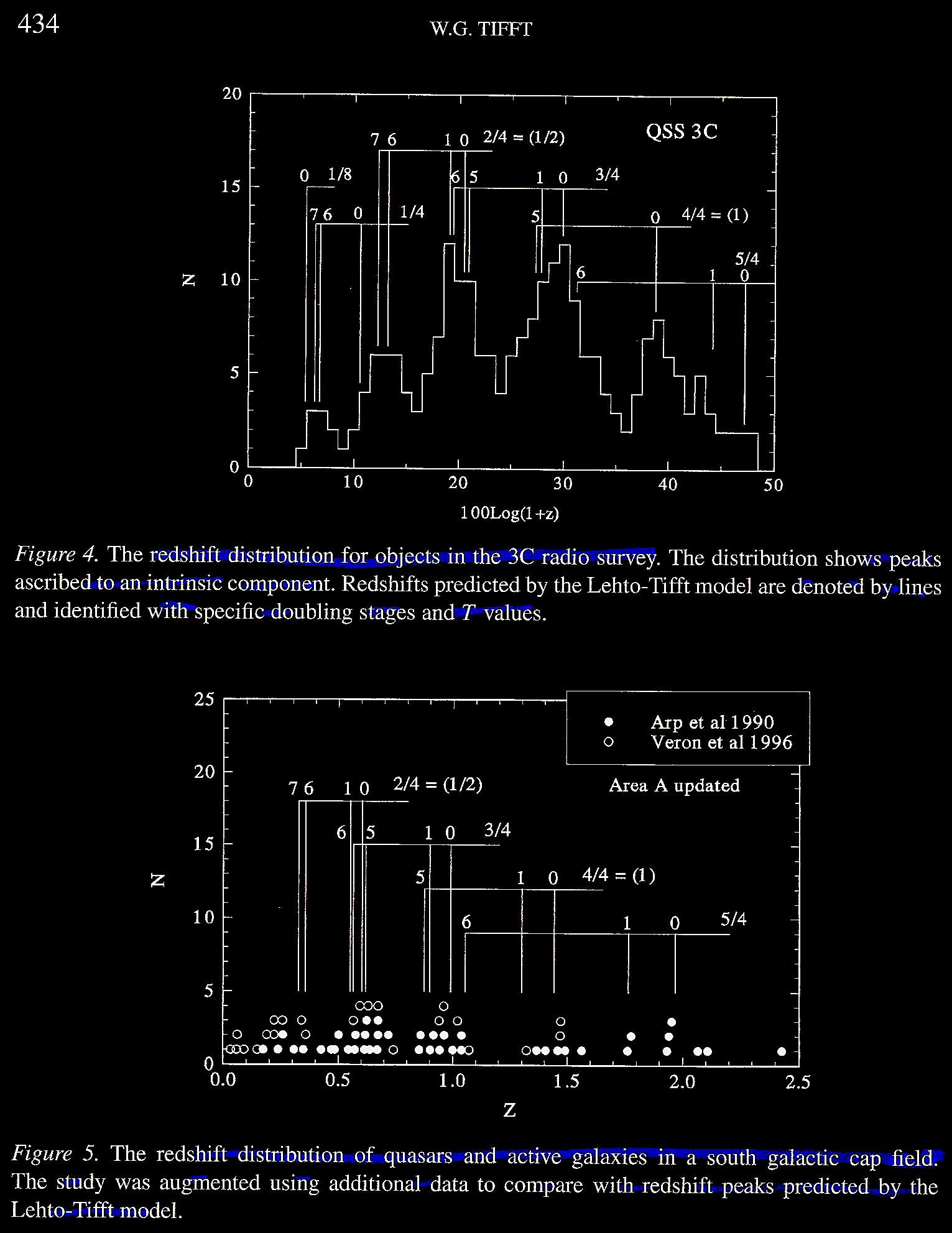

When one adds the full set of the

3rd Cambridge catalog of quasars, one gets

the results in Tifft (2003) Figure 4. In

addition, one can add the quasars from

studies referenced involving the "south

galactic cap field" in Tifft (2003) Figure

5, differentiated by filled and open

circles.

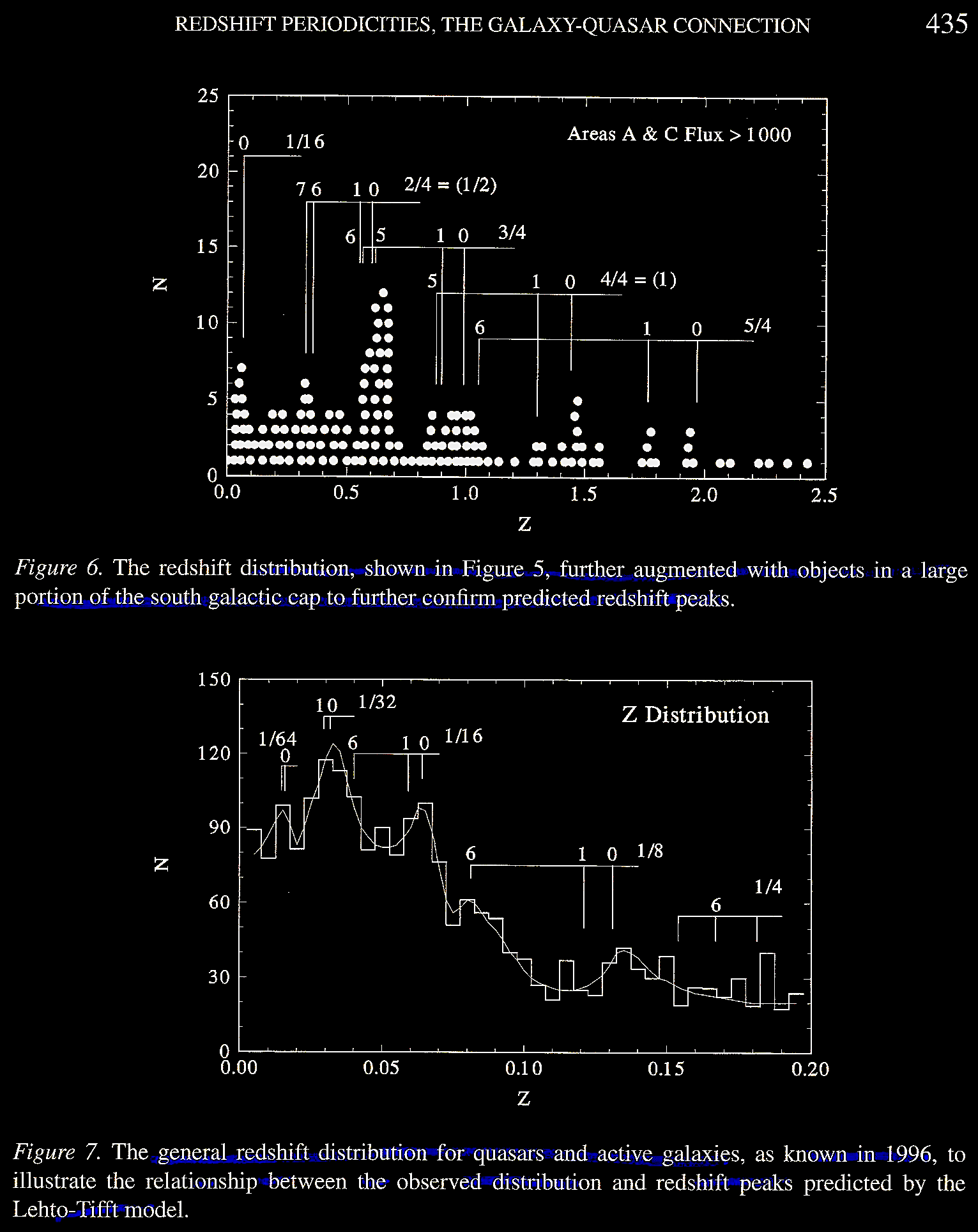

The Karlsson empirical peaks and

the Lehto-Tifft model-predicted peaks

continue to pile higher (Tifft, 2003, Fig.

6) when all of the data from the galactic

southern hemisphere south of the initial

field are included as found in the QSO and

active galaxy catalogue of Veron-Cetty &

Veron 1996. 7th ed. A Catalog of Quasars

and Active Galaxies. ESO Scientific

Report 17. See

https://heasarc.gsfc.nasa.gov/W3Browse/all/veroncat.html.

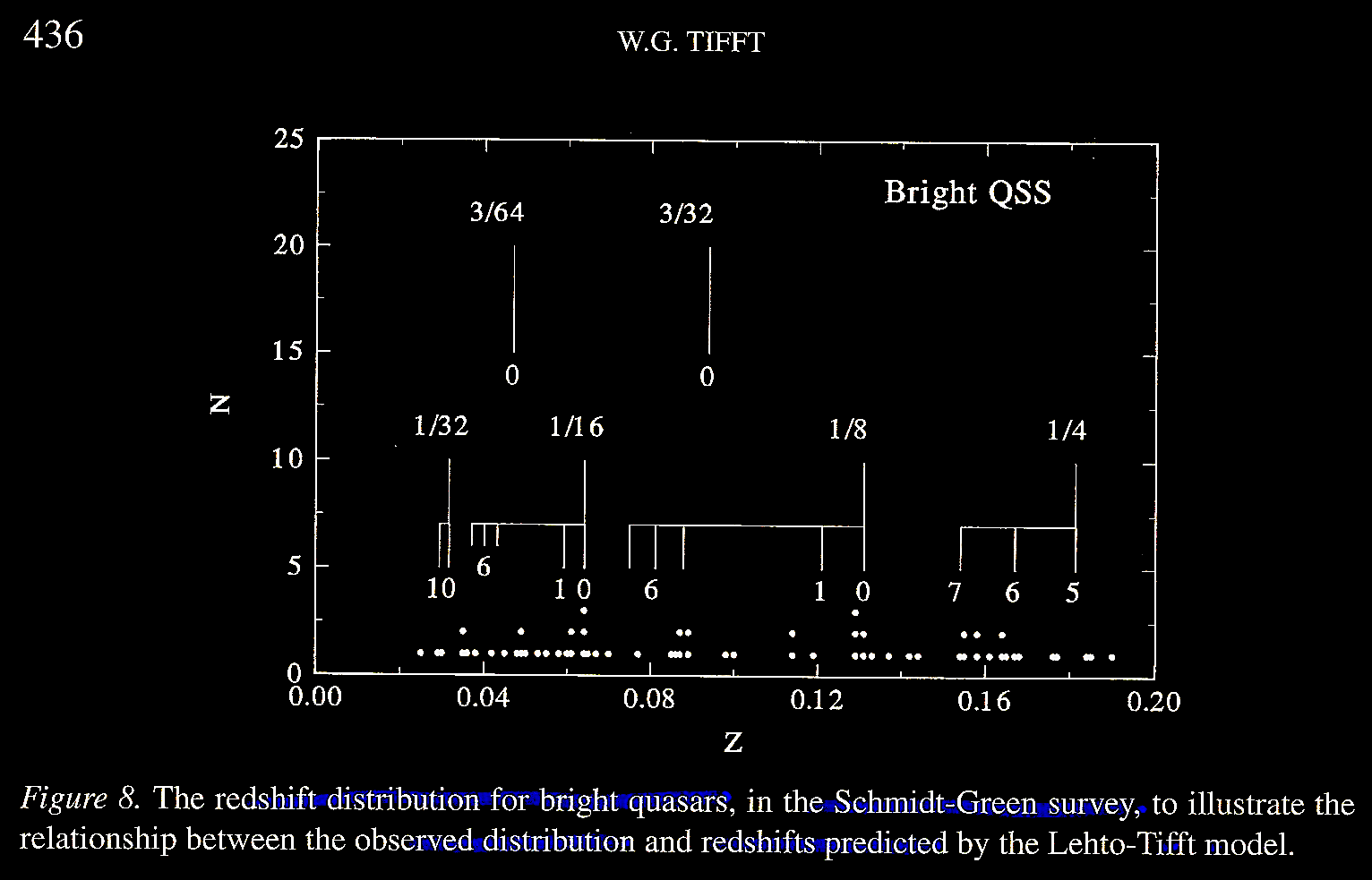

Tifft (2003) Figure 7

shows that there may be

a c/8 peak also.

The trend is extended not on from

the c/8 region but also to the c/16

region of the graph when data from Schmidt,

M. & Green, R. F. 1983. Quasar evolution

derived from the Palomar bright quasar

survey and other complete quasar surveys. ApJ

269, 352. https://articles.adsabs.harvard.edu/full/1983ApJ,

as illustrated in Tifft (2003) Figure 8.

The Lehto-Tifft model suggests

that ongoing Planck unit decay would also

yield less active QSOs and ordinary

galaxies, thus linking galaxies and quasars.

Decay from the first doubling would show a c/2

associated with z = 0.6 quasar peak.

The redshift 'spectrum' would be T =

0 dominant, have various decay product

periodicities, and importantly, "discordant

redshift associations where physically

related objects have decayed into different,

but related states" as has been discussed by

Halton Arp and a few others for years.

Although local decay has gone to D =

12-16, but at z = 0.5, the model

predicts periodicities in D = 4-9,

i.e., c/16 - c/512 (20,000+

to 500 km s–1) range.

In 1995, the Hubble Space

Telescope made a deep and long exposure in a

small patch in the celestial northern

hemisphere called the Hubble Deep Field

(HDF), which provided opportunity to examine

redshifts of faint and distant galaxies.

-1995_15jan1996.jpg)

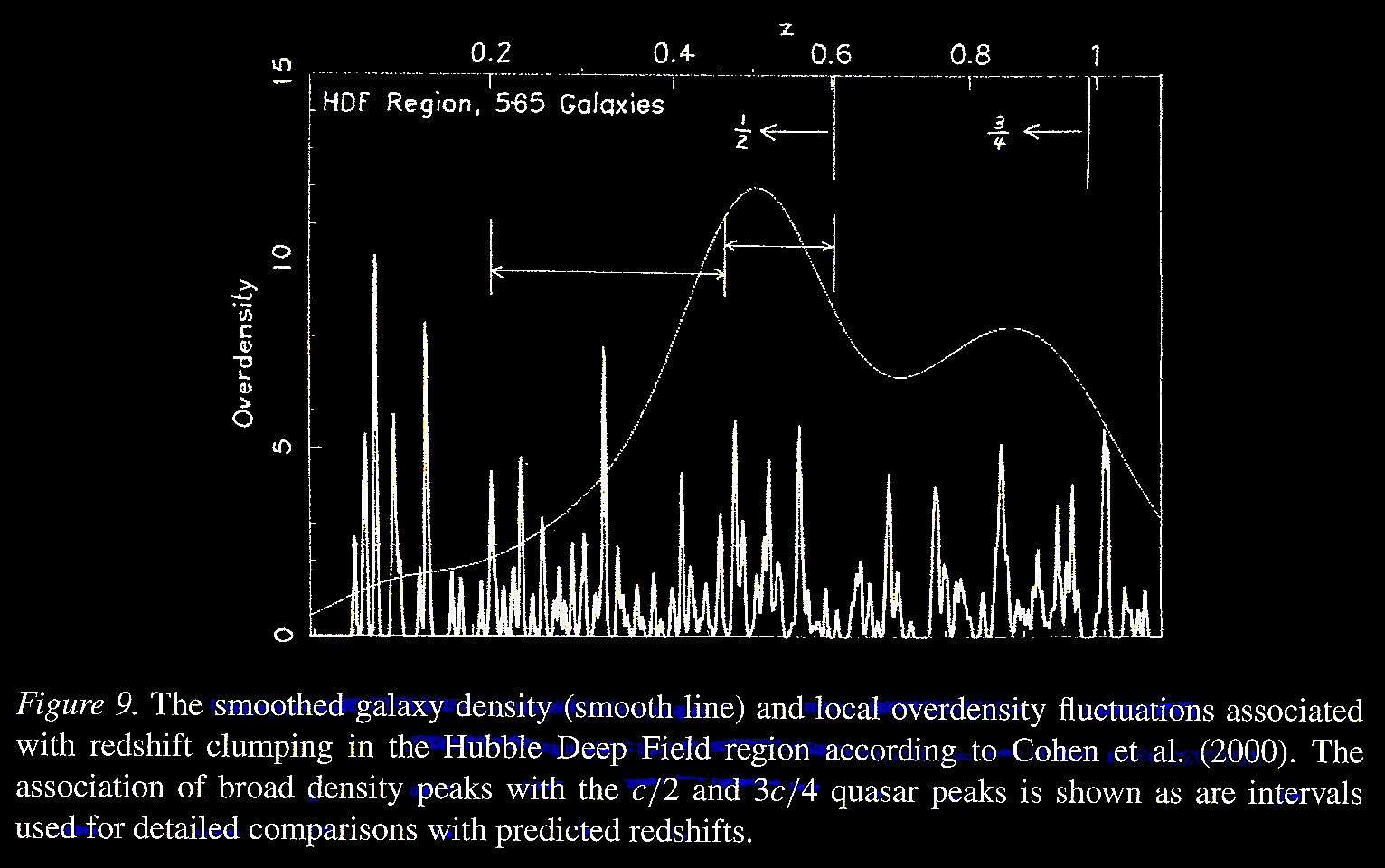

This hypothesis could be tested in

2003 with the Hubble Space Telescope (HST)

Hubble Deep Field (HDF) and Southern Deep

Field (SDF), in Tifft (2003) Figure 9, as

adapted from Cohen et al.

2000. Caltech faint galaxy redshift survey.

X. A redshift survey in the region of the

Hubble Deep Field north. ApJ 538

(1), 29. https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.1086/309096/pdf.

.

.

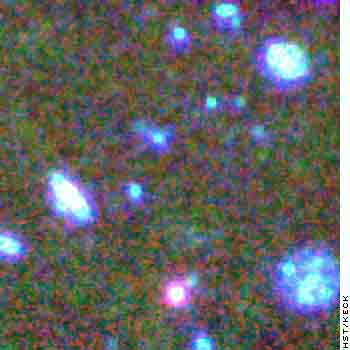

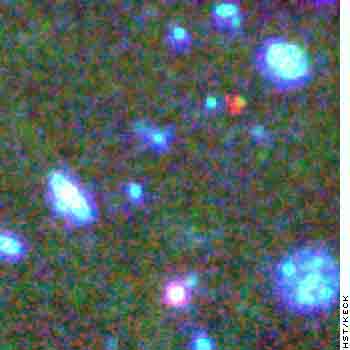

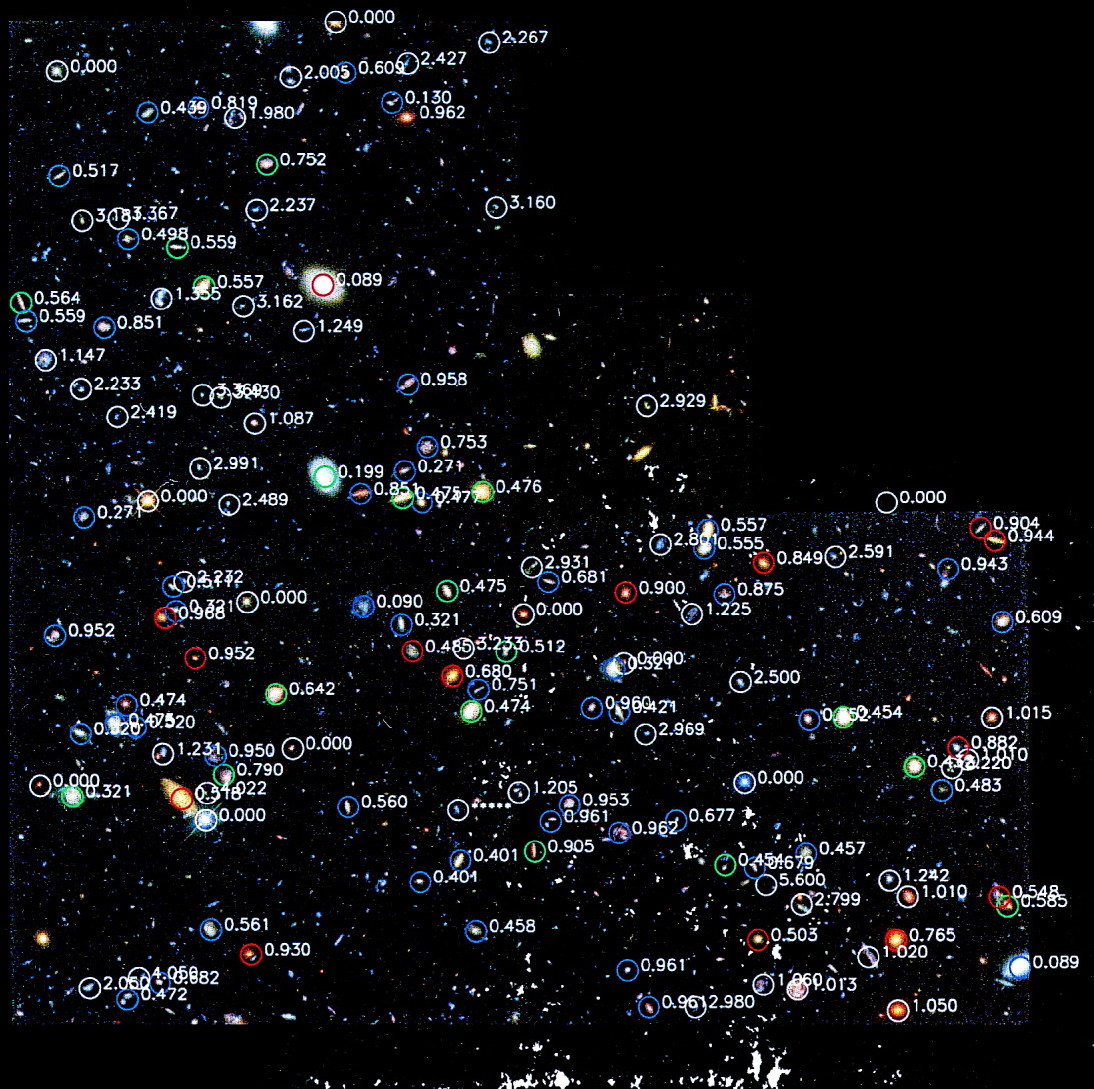

The following Figure 2 from Cohen et al. (2000) superimposes on the HDF the redshifts as well as their color-coded spectral classes, with circles of different colors for redshifts z ≤ 1 and white circles for redshifts z > 1. Cohen and colleagues classified galaxy spectral classes as including galaxies with dominant emission lines (ℰ), galaxies with dominant absorption lines (𝒜), galaxies with intermediate spectra (ℐ), and galaxies with broad emission lines (𝒬). The authors note that starburst galaxies with higher Balmer lines Starburst galaxies with higher Balmer emission lines (Hγ, Hδ, etc.) are classified (ℬ). However, the authors point out, "but for such faint objects, it was not always possible to distinguish them from 'ℰ' galaxies."

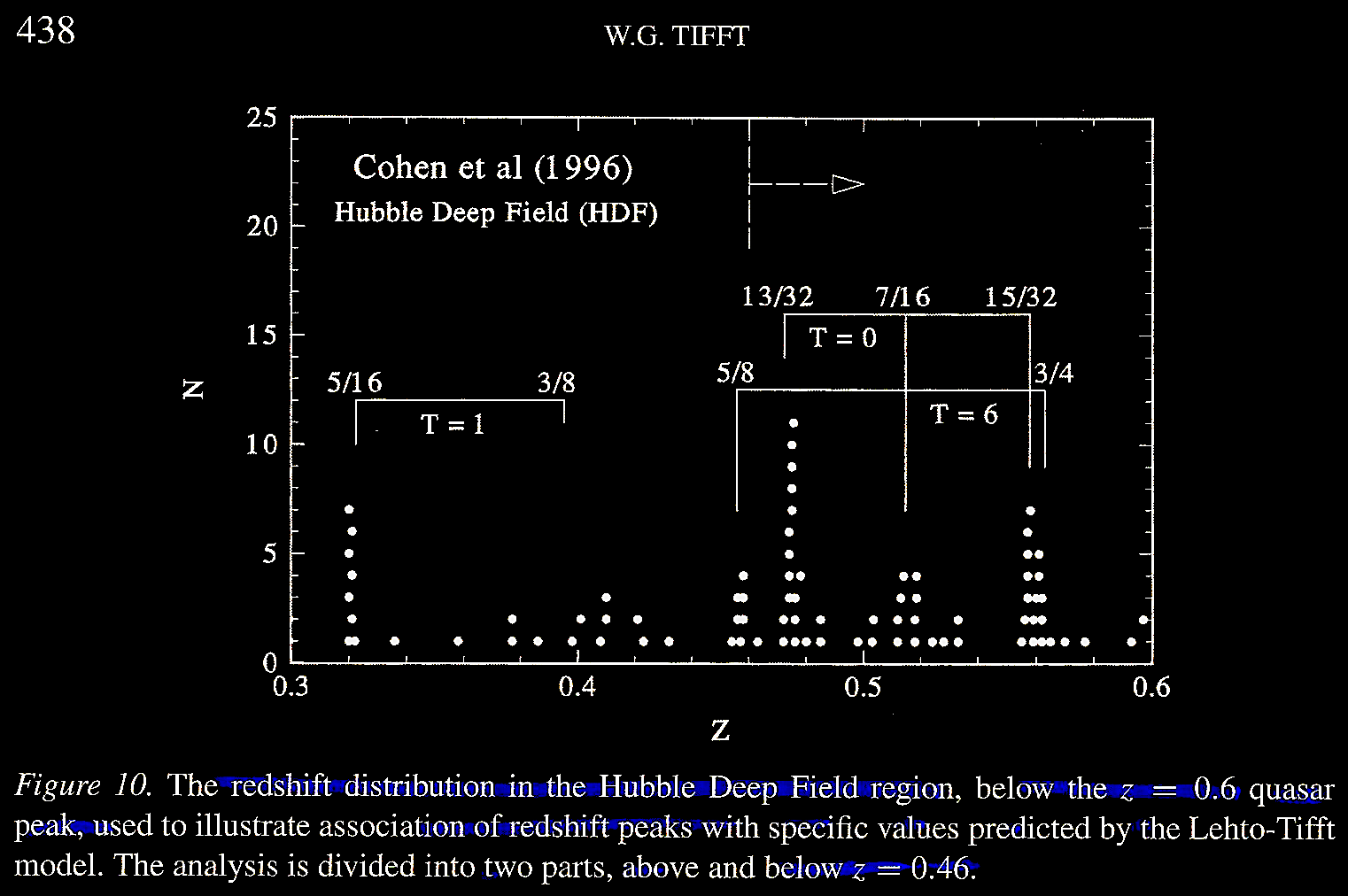

Tifft's first study (1997) used

the data from Cohen et ai. 1996.

Redshift clustering in the Hubble Deep

Field. ApJ 471 (1), L5. https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.1086/310330.

That analysis is seen in Tifft (2003) Figure

10. The model predicted T = 1 and T

= 6 values are present, especially at the c/2,

c/16, and c/32 peaks.

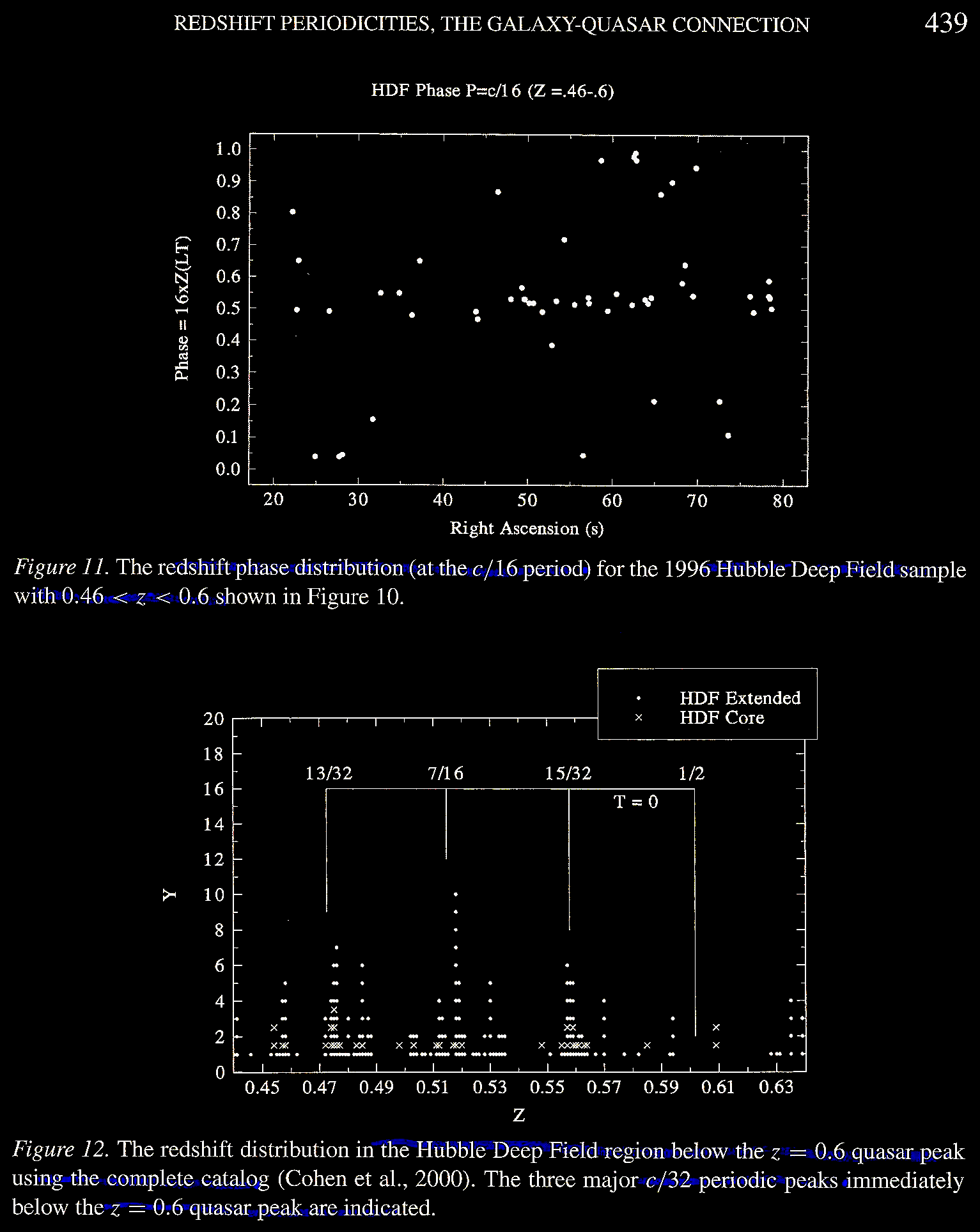

Tifft (2003) Figure 11 showed how

precise is the fit to these three peaks, and

where the strongest peak was. However, a

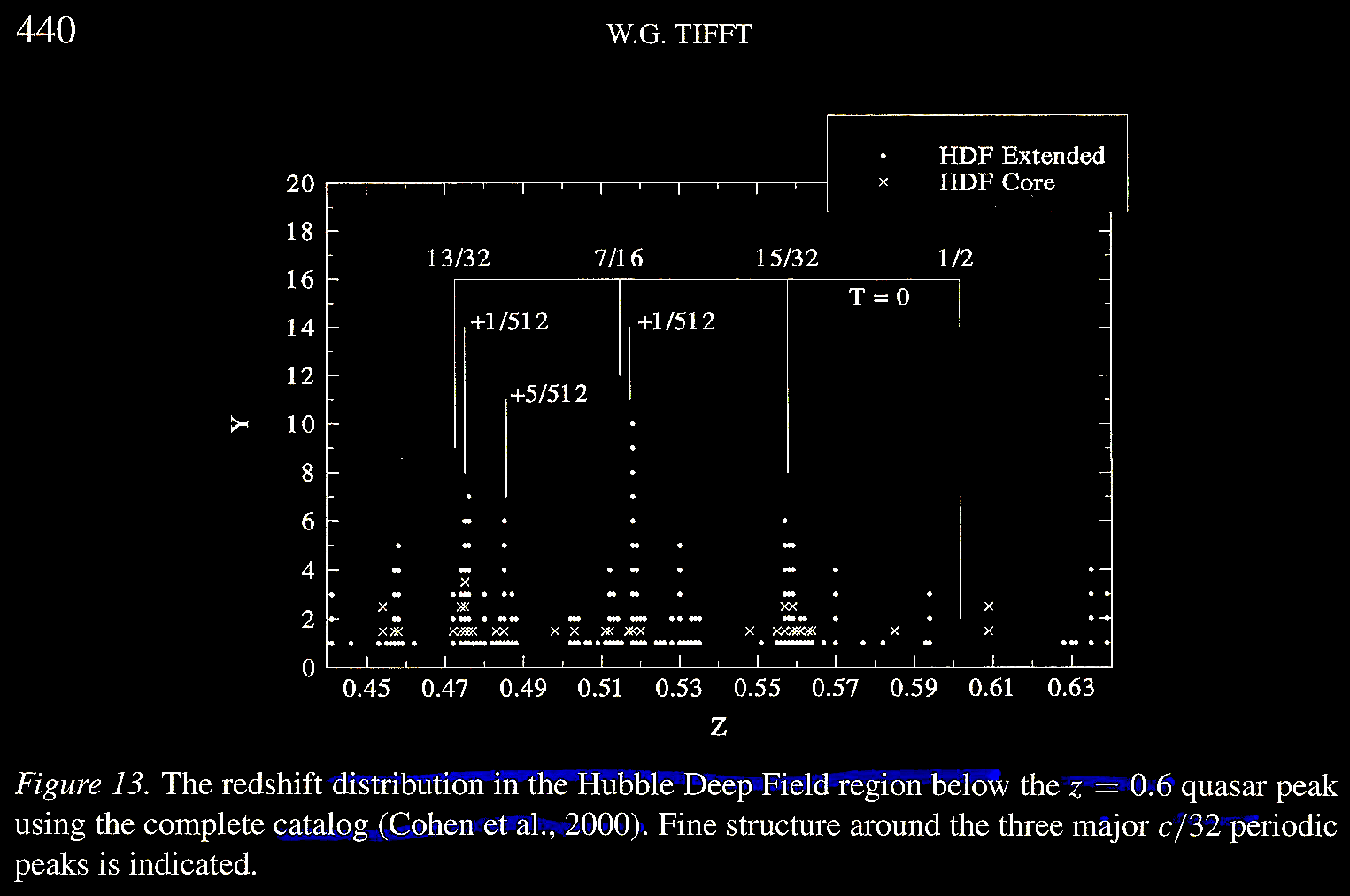

larger sample was needed and became

available with Cohen et al. (2000)

as illustrated in Tifft (2003) Figure

12.

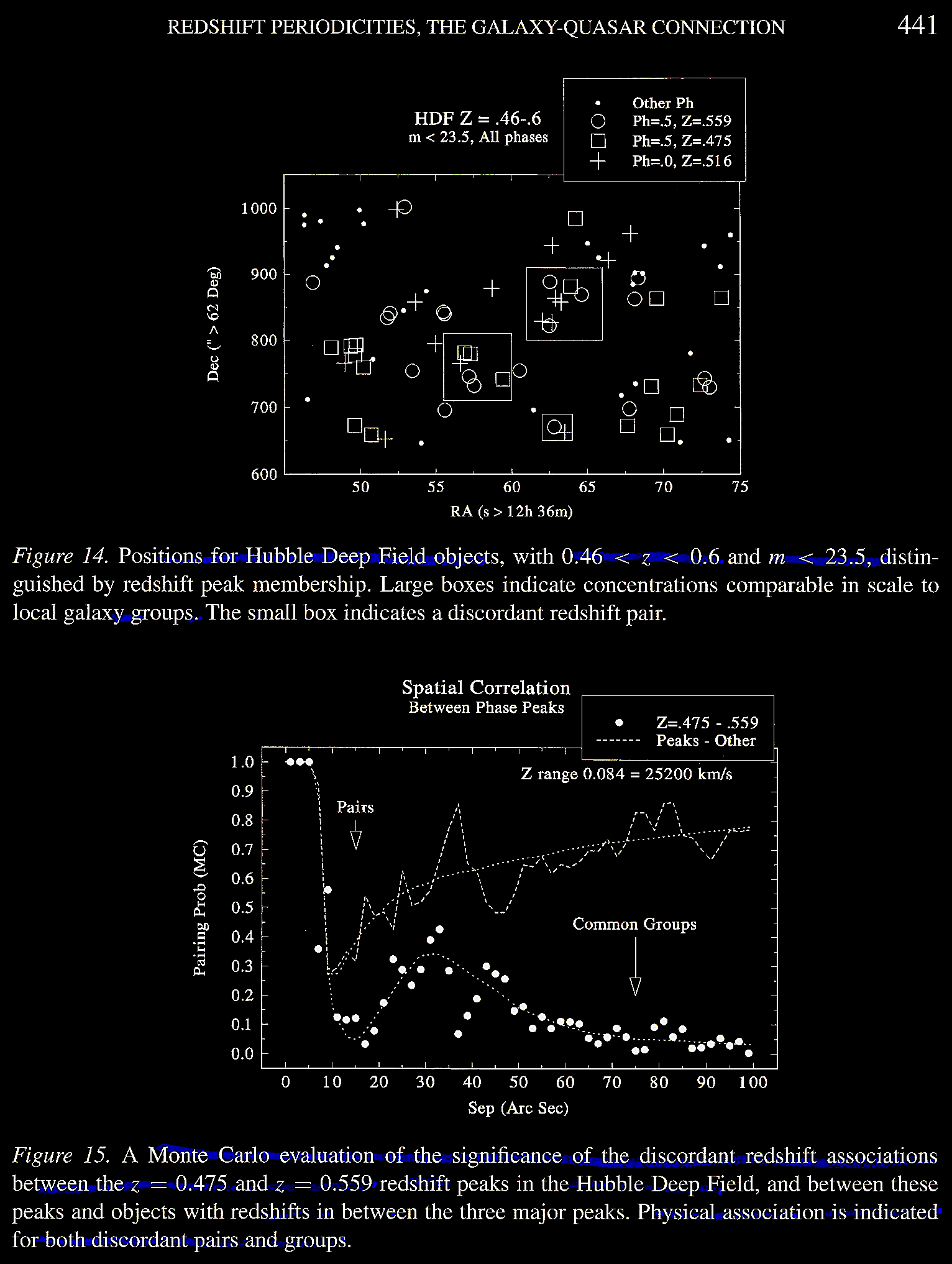

Tifft (2003) Figure 13 shows the

main peaks as well as some "satellite peaks

... offset slightly" from the predicted c/32

and c/16 peaks. Note that all of the

fractions are odd (not even) fractions.

In Tifft (2003) Figure 14, we find

the sky positions of the "extended study"

region of the HDF within certain z

and magnitude (m) values,

designations of galaxy clusters (~1 Mpc),

and also marking of the discordant redshift

pairs of galaxies. Figure 15 shows where

Tifft (2003) asked D. Christein Monte Carlo

statistical analysis of the probability of

pair association by "angular separation"

distribution between pairs of sources with

discordant redshifts compared with 1000

random sample displacements (in RA and Dec)

of objects in one z peak compared

with another. Figure 15 also shows the

difference between two peaks separated to

the extreme by redshift values equivalent to

25,000 km s–1, showing evidence

of clear physical association.

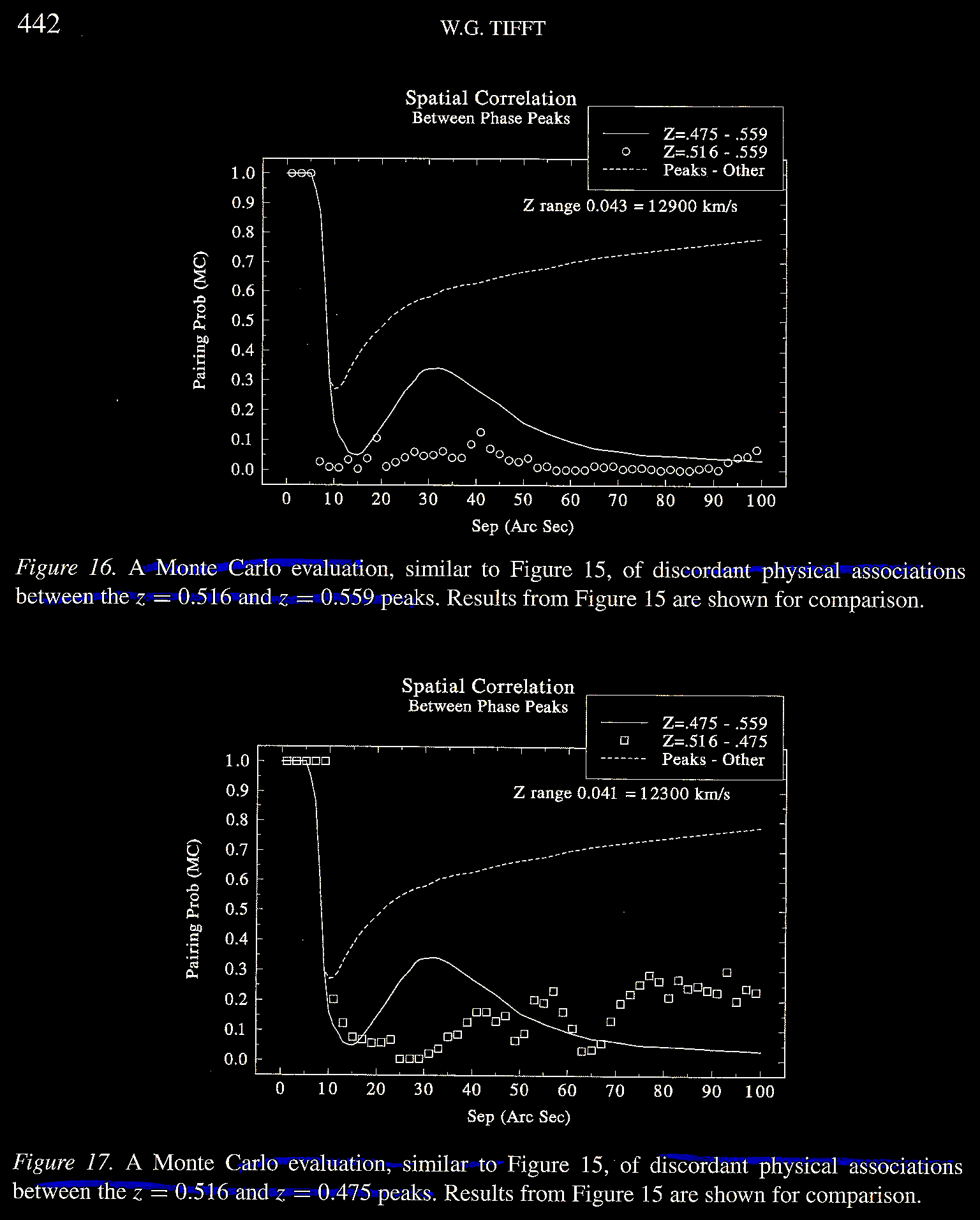

Tifft's (2003) Figures 16 and 17

show the Monte Carlo association analysis

for adjacent peaks with discordant redshift

differences equivalent to the moderate

12,000-13,000 km s–1

range.

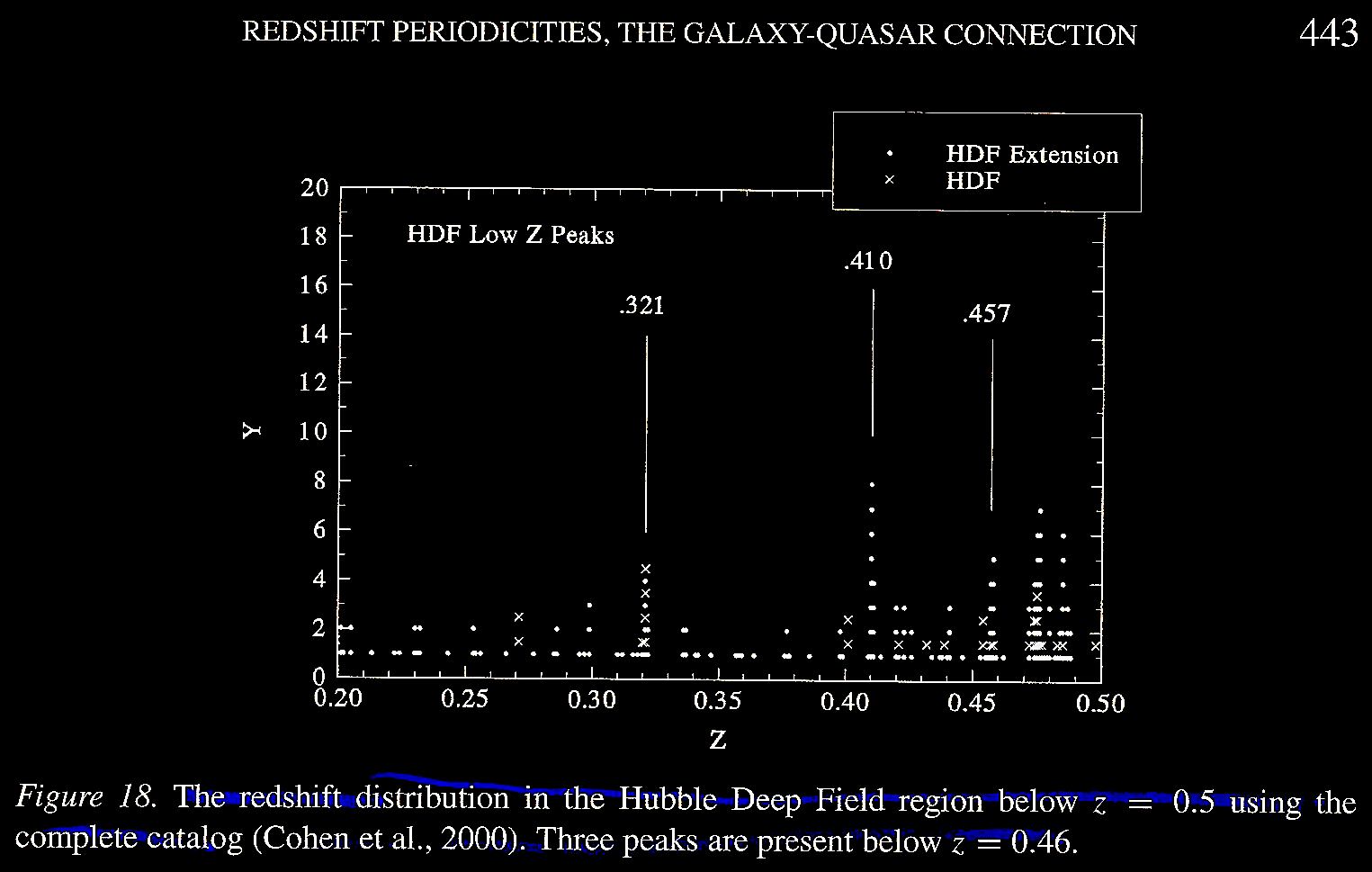

Just as they had done HDF

extensions into the higher redshift values,

Tifft (2003) extended the search for

redshift peaks into the lower redshift

values in Figure 18.

Just as satellite 'phase' peaks

have been observed around certain values in

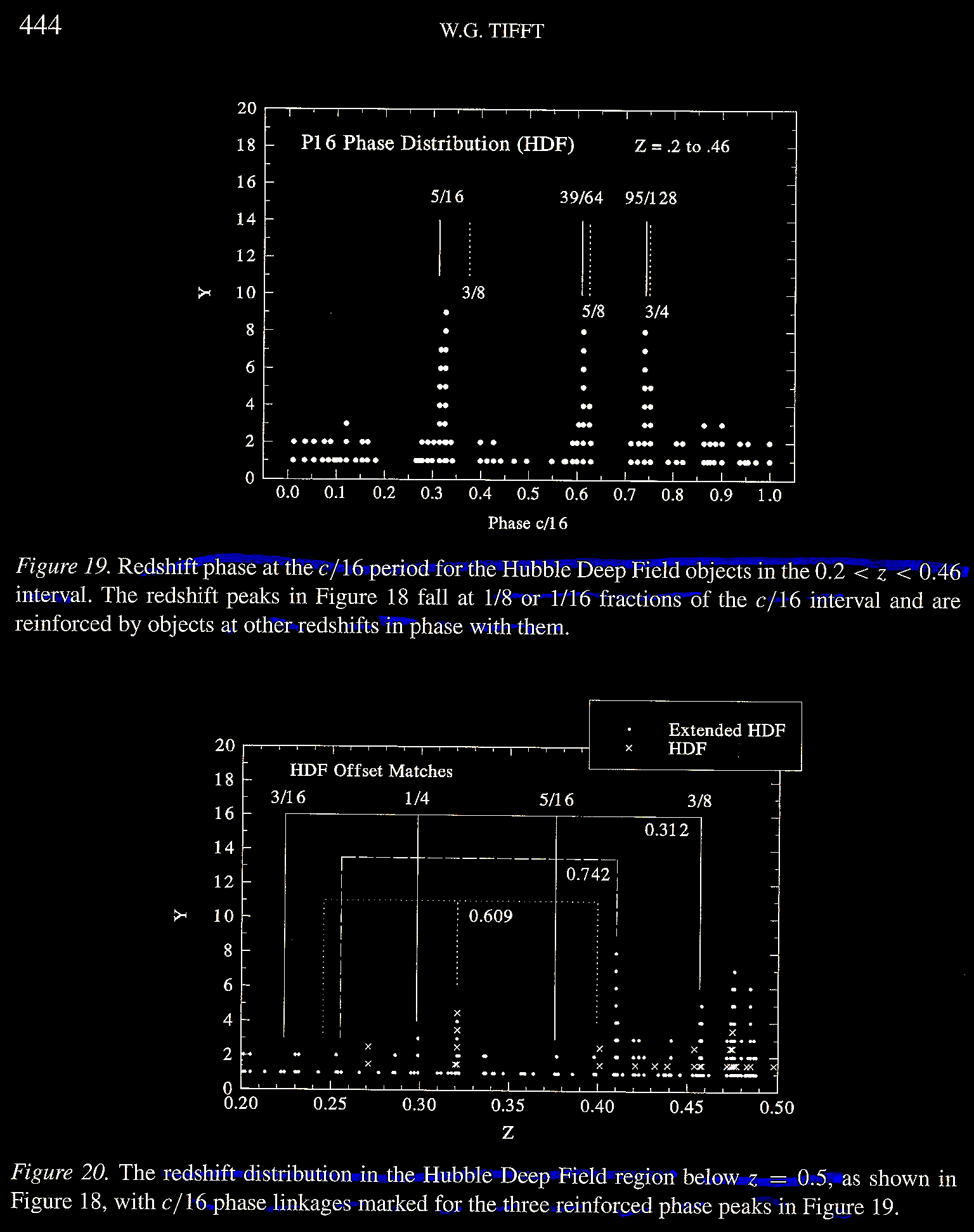

the HDF, Tifft (2003) Figure 19 shows

'phase' peaks around the value c/16

for the data range of 0.2 < z

< 0.46. Figure 20 shows 'phase' or

satellite peaks around c/16 for z

< 0.5.

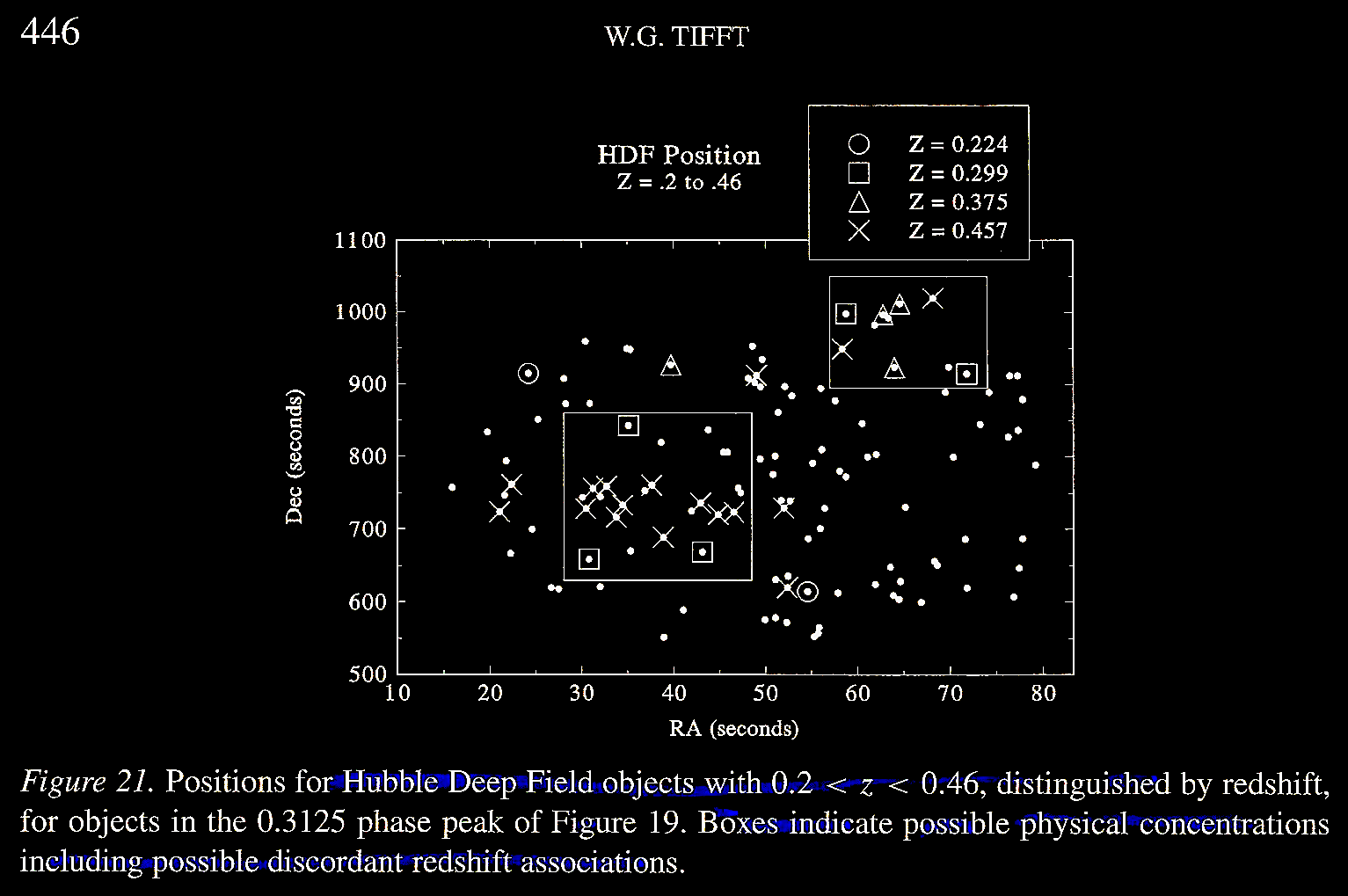

The last step in

analyzing the lower redshift cohort for Tifft (2003) was to

locate their positions on the celestial sphere in RA and Dec

(Figure 21), in order to assess which 'clumpings' may

represent physical associations between sources with

discordant redshifts. Again, there are suggested physical

associations of galaxies with discordant redshifts.

In 1998, another deep exposure was

taken with the HST called the Hubble Deep

Field South (HDFS; https://stsci-opo.org/STScI

from https://hubblesite.org/contents/media/images/1998/).

Cf. full

story link. Even under the ideal

Earth-based conditions at the Cerro-Telolo

Inter American Observatory, this is the

Earth-bound view of the HDFS region of the

sky:

Credit: J. Gardner (NOAO/GSFC), Cerro Tololo Inter- American Observatory (https://hubblesite.org/contents/media/images/1998/).

_23nov1998.jpg)

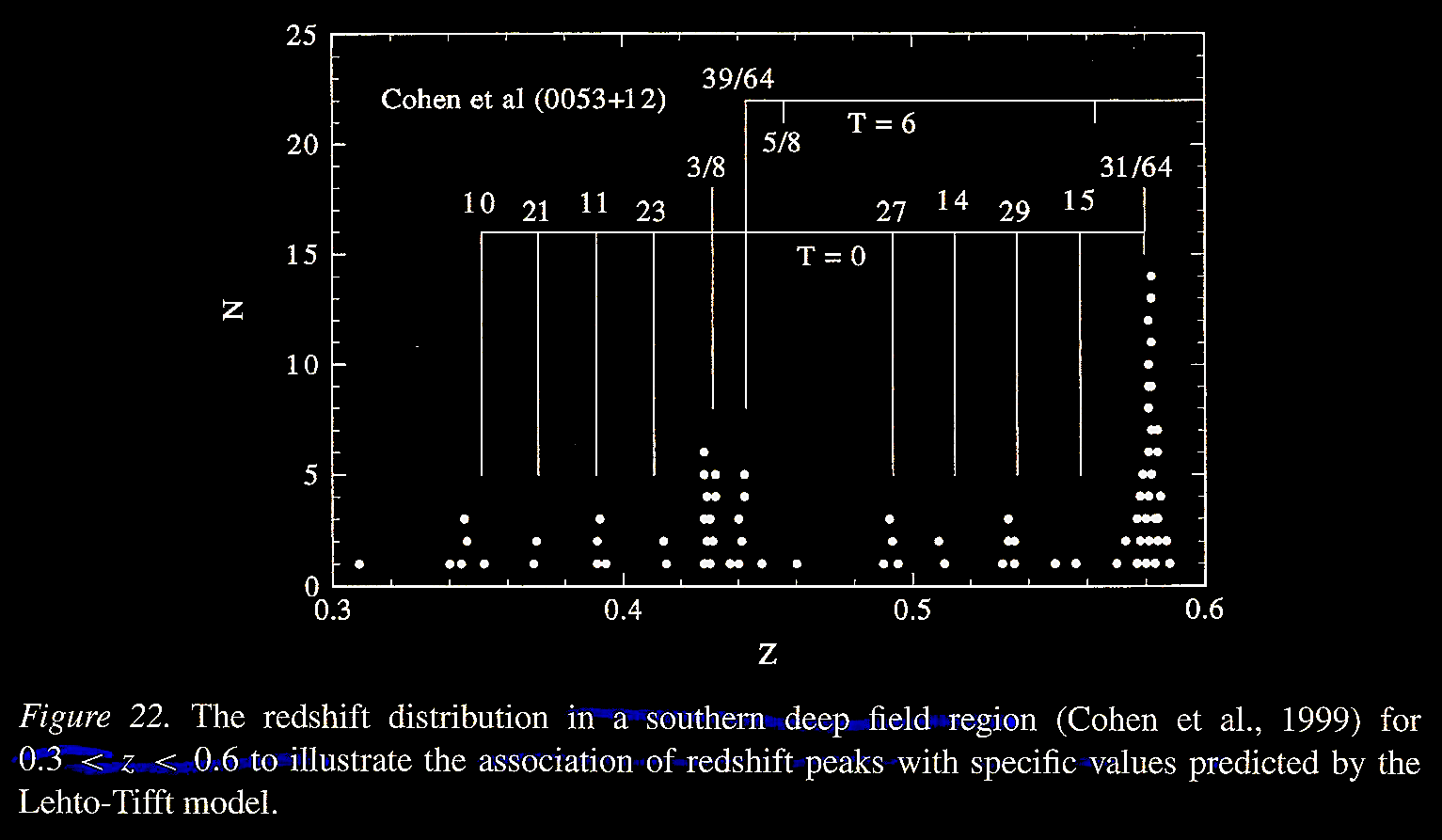

The HDF findings were tested on

the HDFS. It is no surprise that such

periodicities were found there as well in

the opposite celestial hemisphere. Tifft

(2003) Figure 22 shows sources with

redshifts from 0.3 < z < 0.6,

and sure enough, there are stark

periodicities in the predicted T = 0

around c/64 and c/32, as

well as some peaking associated with the T

= 6 state.

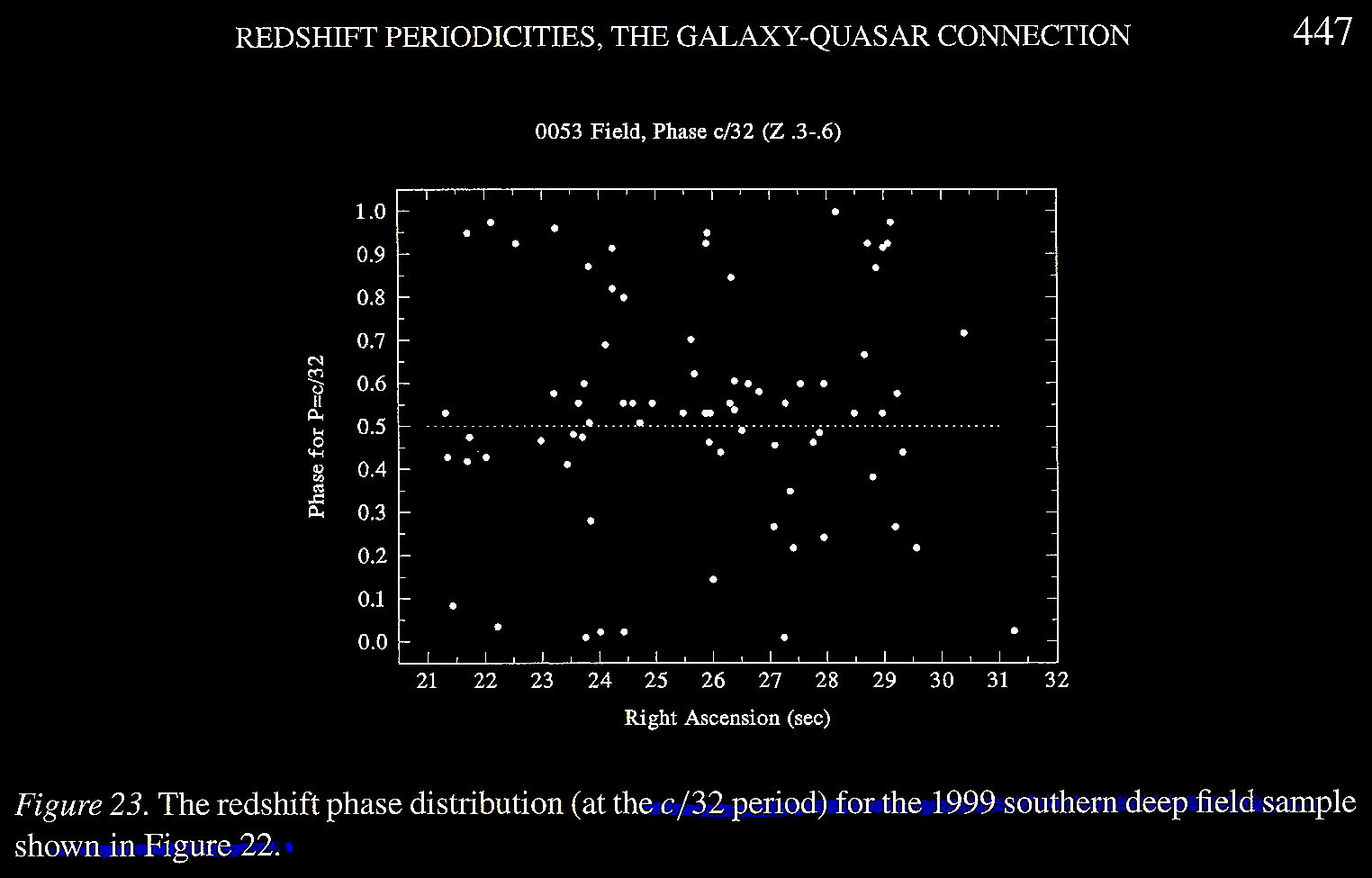

Tifft (2003)'s Figure 23 shows the

'phase' peaking around the c/32

periodicity in the HDFS.

Summary on the Lehto-Tifft

model. The Tifft (2003) study was

presented at a conference of friends,

colleagues, and some old rivals honoring the

widely-loved and admired, great astronomer

and cosmologist Sir Fred Hoyle and the quest

to "better understand the cosmos that Fred

so loved." Sir Fred would have much enjoyed

the presentation, pouring over the data, and

a bracing discussion. While the Lehto-Tifft

model shows a striking agreement of

numerical results with a model of redshift

periodicity built up from the use of a

double decay process from the Planck state,

it still is a pattern-fitting empirical

model, which only hints at the processes

underneath. We note the importance of the

model of these astounding data which are so

unexplained in standard HBB cosmology, and

as the literature cited above references,

mainstream cosmologists have tended to

dismiss or pretend that the redshift

periodicities are not real phenomena. In

what follows, we will explore a little more

data bringing us up to more contemporary

times, and some other possible cosmological

models to explain these data. (Other reading

and resources can be found at link

& link).

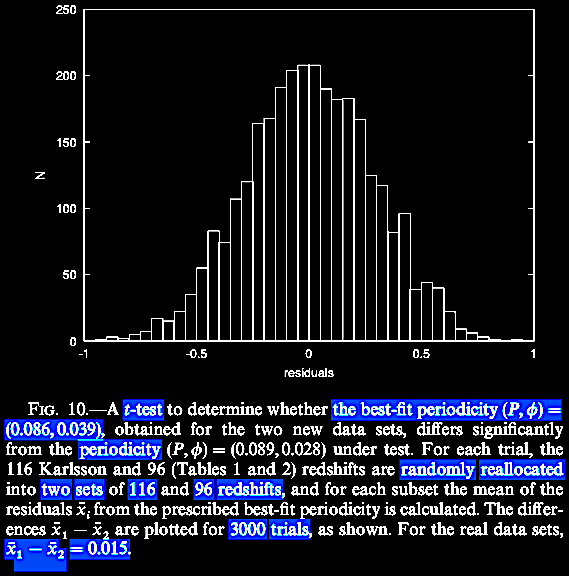

Return

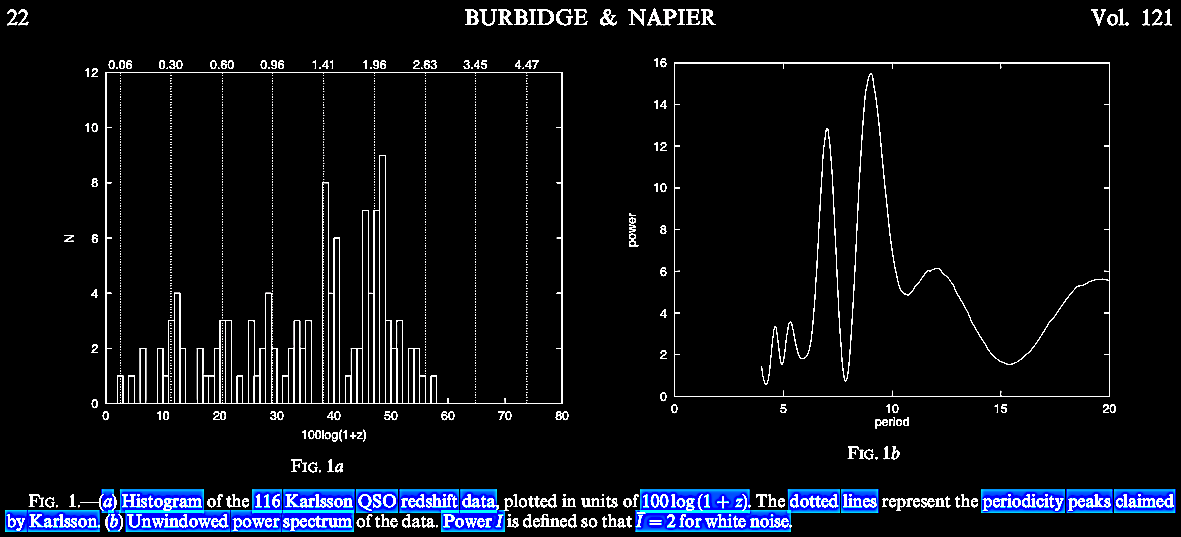

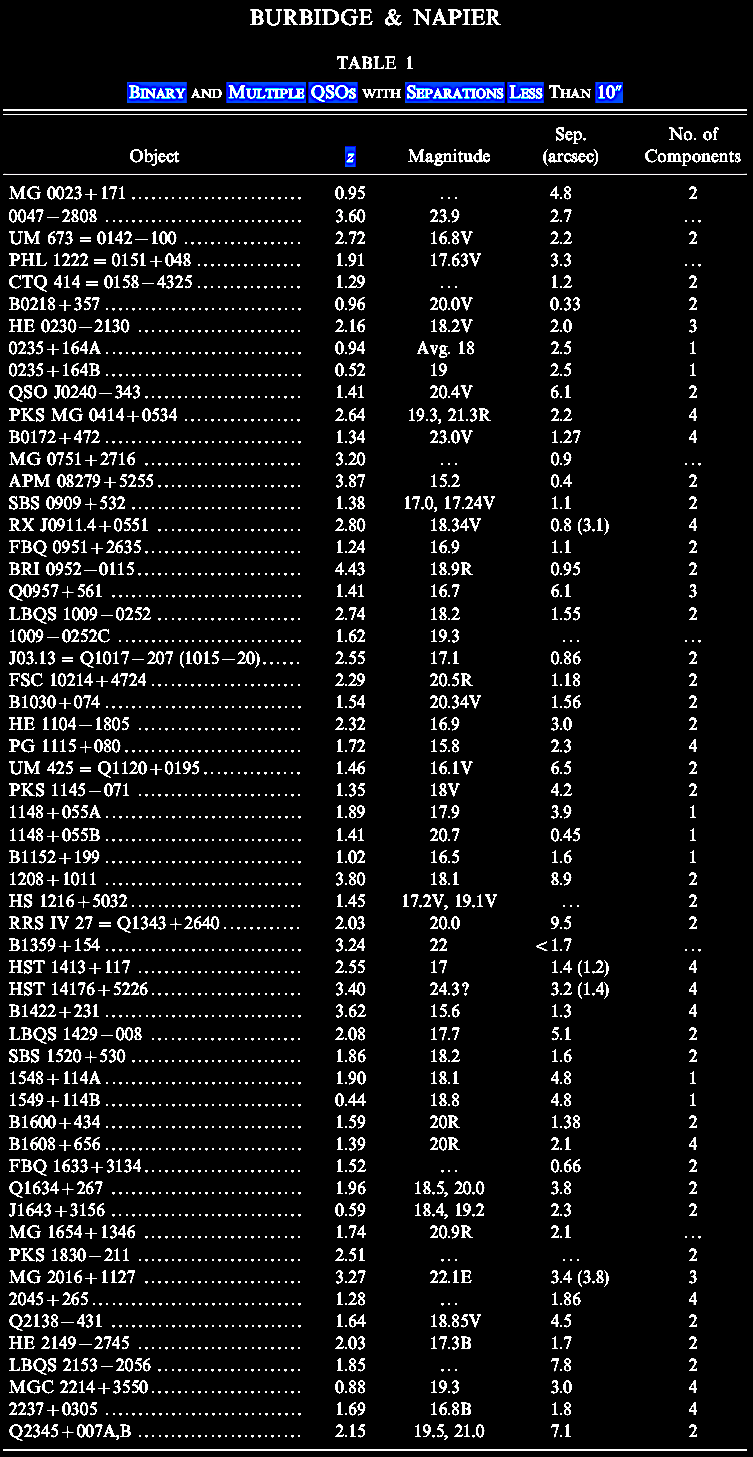

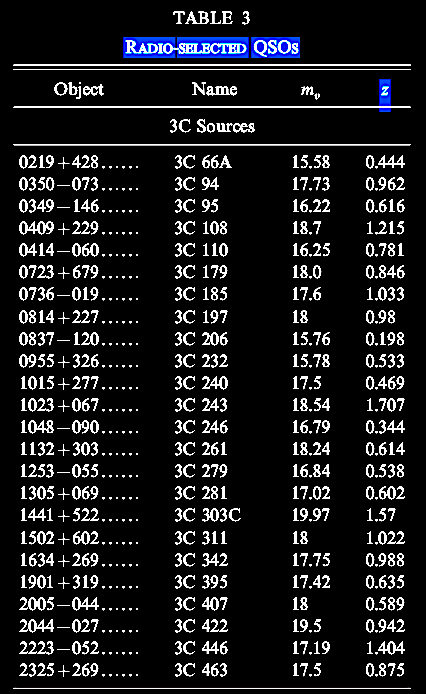

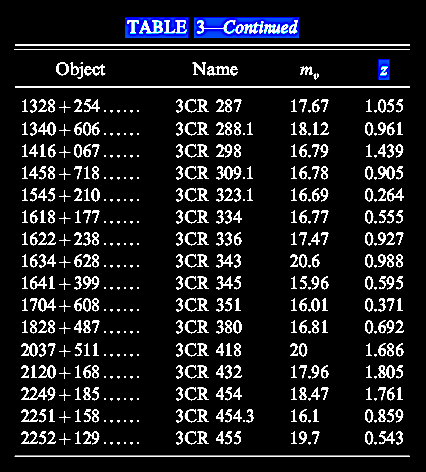

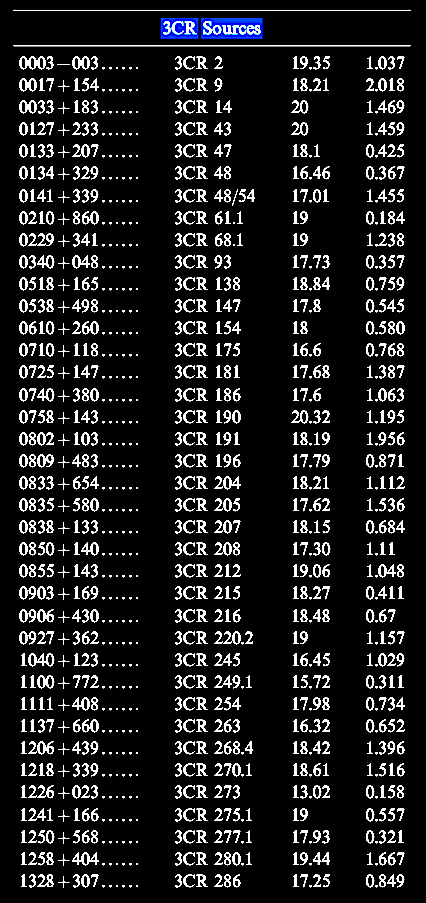

to the Karlsson periodicity. We return to the Burbidge

& Napier (2001) paper. Ever since 2001 with more

complete sets of quasar data, Burbidge, G. & Napier, W.

M. [2001. The distribution of redshifts in new samples of

Quasi-stellar Objects. AJ 121 (1), 21. https://doi.org/10.1086/318018]

found direct observational evidence for the next set of

predicted by the Karlsson formula of redshift periodicity

peaks, z = 2.63, 3.45, and 4.47, beyond what had

been empirically observed up to then. In careful fashion,

Burbidge & Napier (consulting with Margaret Burbidge and

Sir Fred Hoyle) not only ran statistical tests but laid out

the possible interpretations or hypotheses to explain these

data.

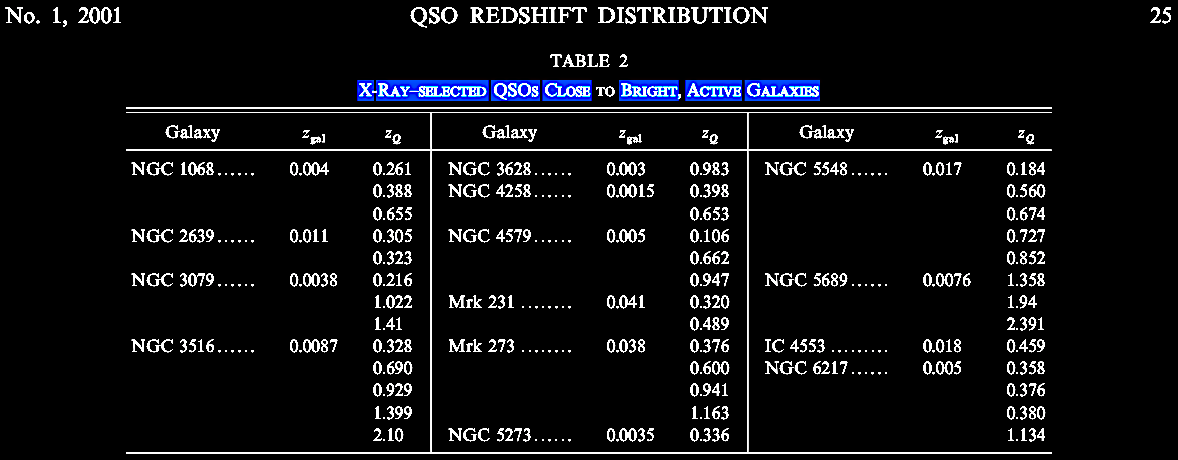

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Table 3

continuing with 3C radio sources: z-values in

the 4th column: |

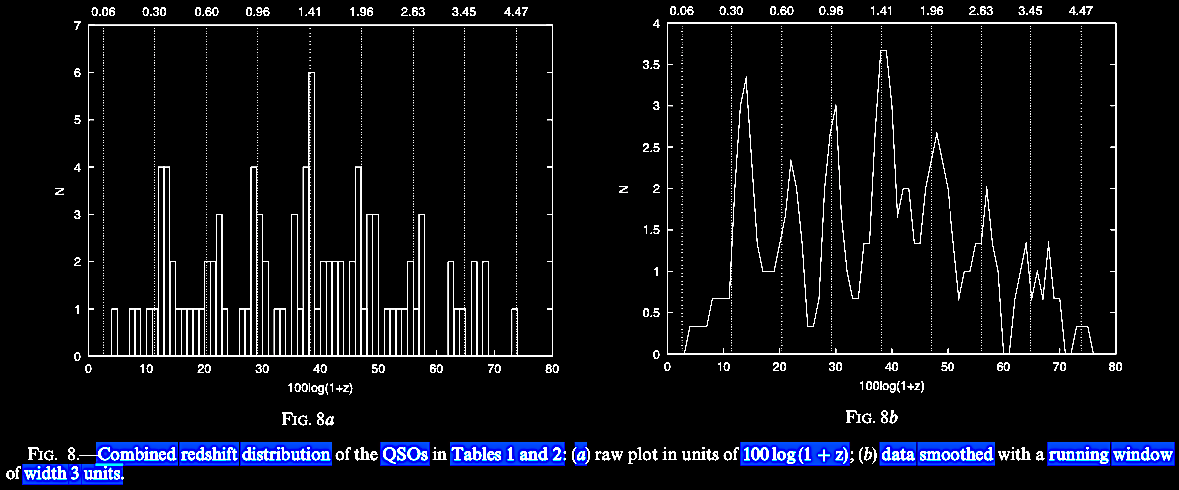

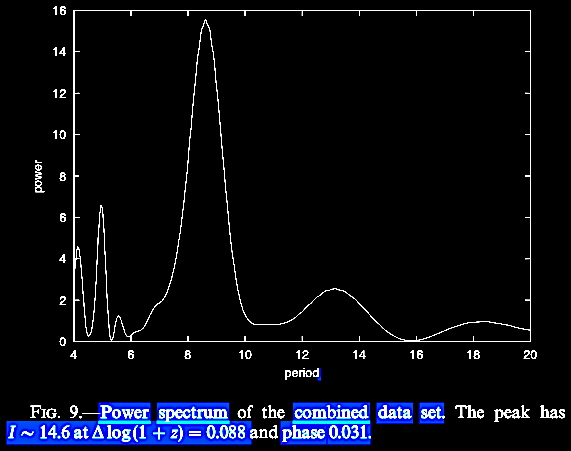

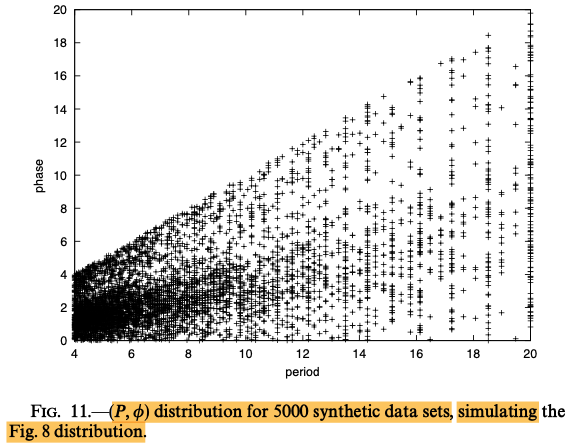

With the QSO data

available in 2001, the Karlsson periodicity continued to

appear and extend beyond and confirming previous predictions.

In 2009, Burbidge

& Napier published another paper, Associations of

high-redshift Quasi-Stellar Objects with active, low-redshift

spiral galaxies. ApJ 706 (1), 657. https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.1088/0004-637X/706/1/657,

where they were able to affirm that the statistically-robust

associations between higher redshift quasars and lower

redshift galaxies in earlier data sets remained, but were

unable to reproduce the results with a partial data set from

the SDSS at that point. The observations suggesting

associations between low redshift active galaxies and higher

redshift continued to build on the trend since the 1950s and

1960s, where the Ambartsumian-Vorontsov-Vel'yaminov-Arp (AVVA)

ejection cosmogony of galaxies recommends itself as a model

(see the discussion in chapter IX. Vast jets and galactic ejection

phenomena: Mass origin-ejection?).

A

year before the courageous and persistent dissident

observational astronomer Halton Arp's death, more results

were published on the 2dF survey in Fulton, C. C. & Arp,

H. C. 2012. The 2df Redshift Survey. I. Physical association

and periodicity in quasar families. ApJ 754

(2), 134. https://doi.org/10.1088/0004-637X/754/2/134.

(Some of the curated data has been placed at http://casjobs.sdss.org/CasJobs/

and http://tdc-www.cfa.harvard.edu/2mrs/2mrs_v240.tgz).

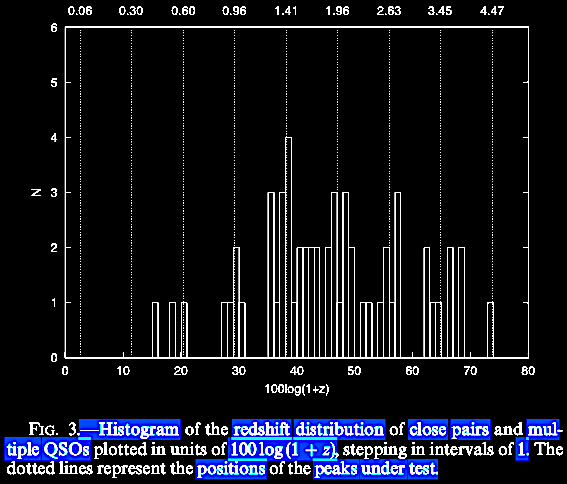

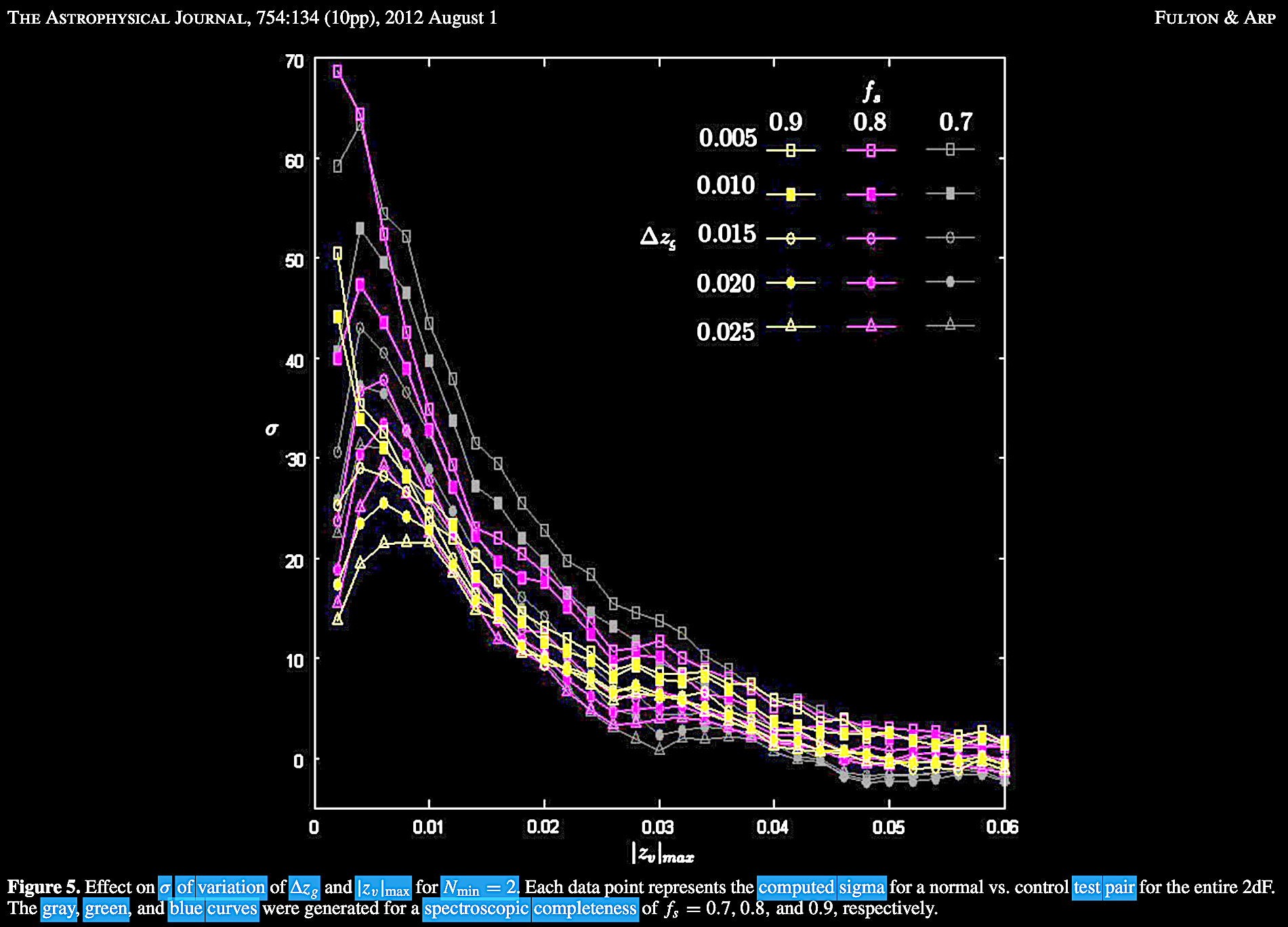

They examined data from the 2dF Galaxy Redshift Survey

(2dFGRS) and from the 2dF Quasar Redshift Survey (2QZ) in

the two declination strips at Dec 0o and -30o.

In order to avoid a range of mixed redshifts of galaxies and

quasars, they filtered out all but quasars z

≥ 0.5. Making no mention of the Lehto-Tifft model, Fulton

& Arp searched for Karlsson-type periodicity in quasar

redshifts. Around each galaxy, they detected quasars which

conform to "empirically derived constraints based on an

ejection hypothesis." They "ran Monte Carlo control trials

against the pure physical associations by replacing the

actual redshifts of the candidate companion quasars with

quasar redshifts drawn randomly from each respective ...

[R.A.] hour." When properly constrained for quasar z

grouping and the Karlsson periodicity, the 2dF data showed

that the Karlsson periodicity is statistically significant,

and not a selection effect (Fulton & Arp, 2012; Figure

5).

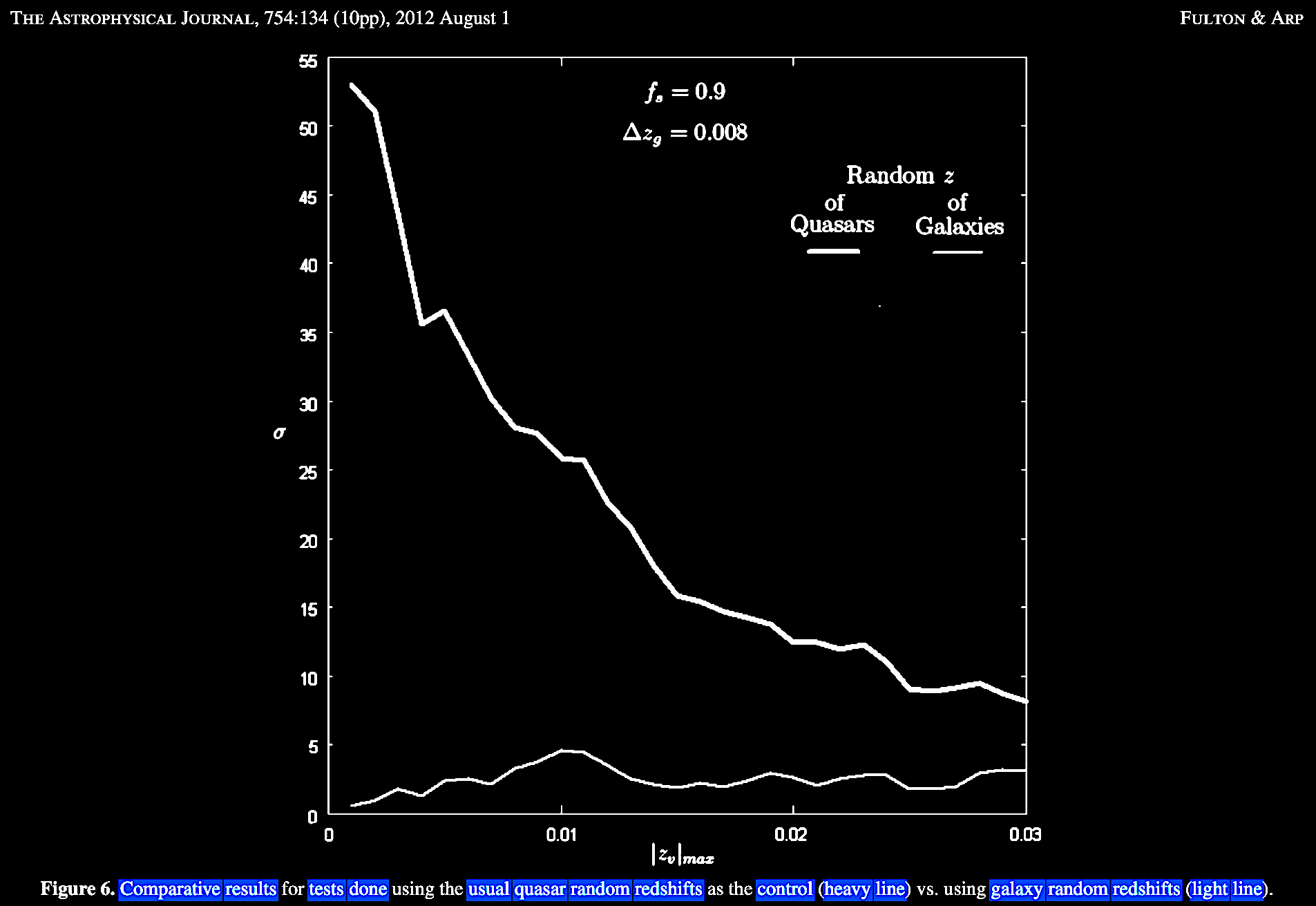

Fulton

& Arp (2012) Figure 6 shows that the presence of

discordant redshift data between physically connected

galaxies and quasars has been shown to be statistically

significantly.

One

of the more recent papers which has attempted to pull

together the data on redshift periodicity and compare

theoretic explanations was first submitted for publication

in 2016, but only published in 2020, indicating the ongoing

difficulty of suggesting alternative hypotheses for unusual

phenomena in cosmology, and getting them published. That

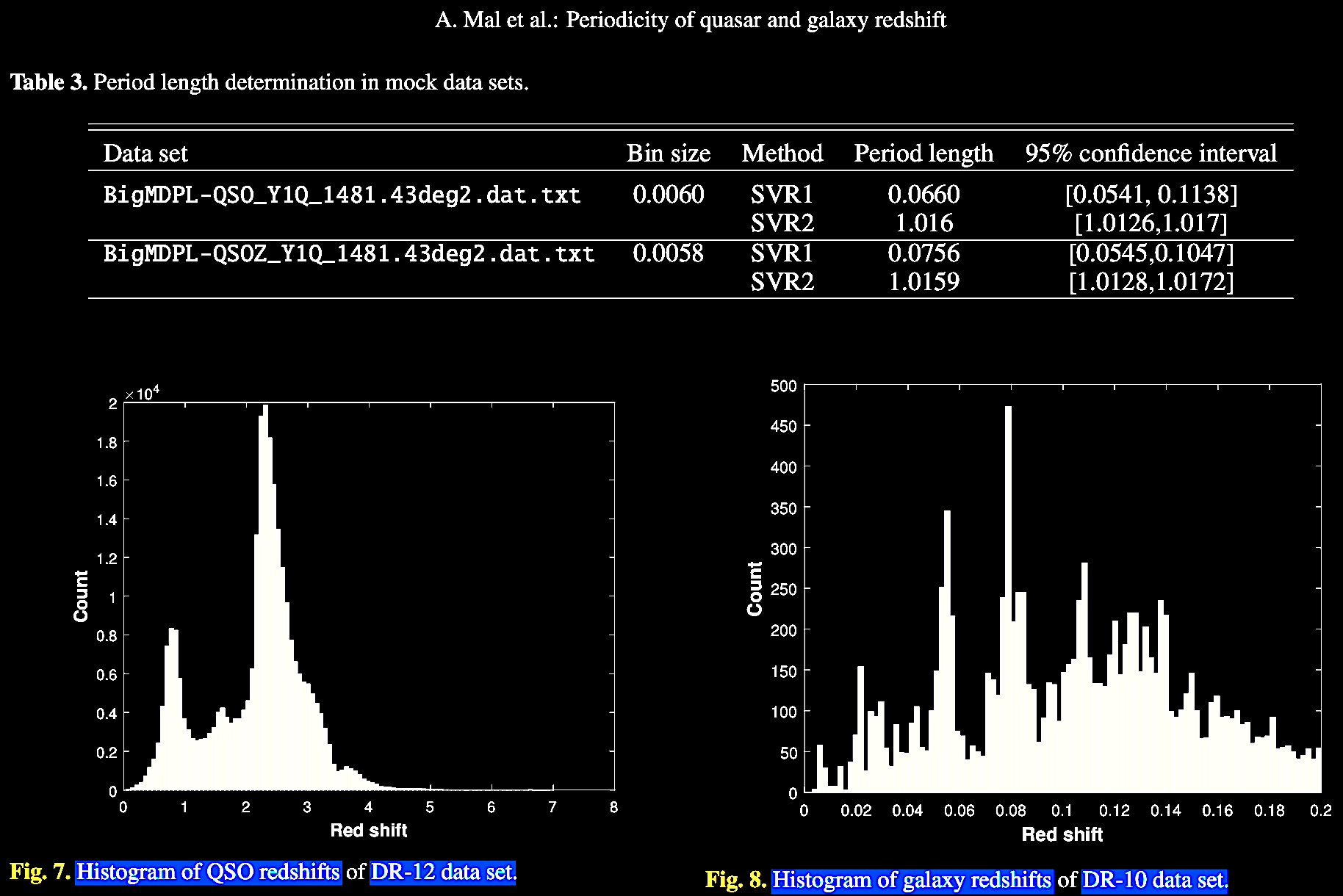

paper is from an Indian group, Mal et al. 2020.

Periodicity of quasar and galaxy redshift. Astron &

Astroph. 643, A160. https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/201630164.

They briefly and informally review >5 decades of

published research on periodic redshift data. As already

noted, there have been empirical / numerical formulations of

the periodicities observed. And there've been attempts, as

seen above, to model the causes of the observed

periodicities. For example, Depaquit, S., Pecker, J. C.

& Vigier, J. P. 1985. Astron. Nachr. 306

(1), 7. https://adsabs.harvard.edu/full/1985AN,

argued that the periodicities were caused by (1) a selection

effect from data sampling; (2) the non-randomness of quasar

distribution in the Universe, and (3) the presence of

Dopplerian / non-Dopplerian contributions to redshift. Lehto

(1990. Chin. J. Phys. 28, 215) and Tifft

(1997; 2003) proposed their developed explanation, discussed

above.

In

2007, Bajan & Flin published a review called, Redshift

periodicity. Old New Concepts Phys. IV, 159.

http://merlin.phys.uni.lodz.pl/concepts/2007_2/2007_2_159.pdf,

in which they reviewed studies published since the late

1960s up to their date on the redshift periodicity issue. In

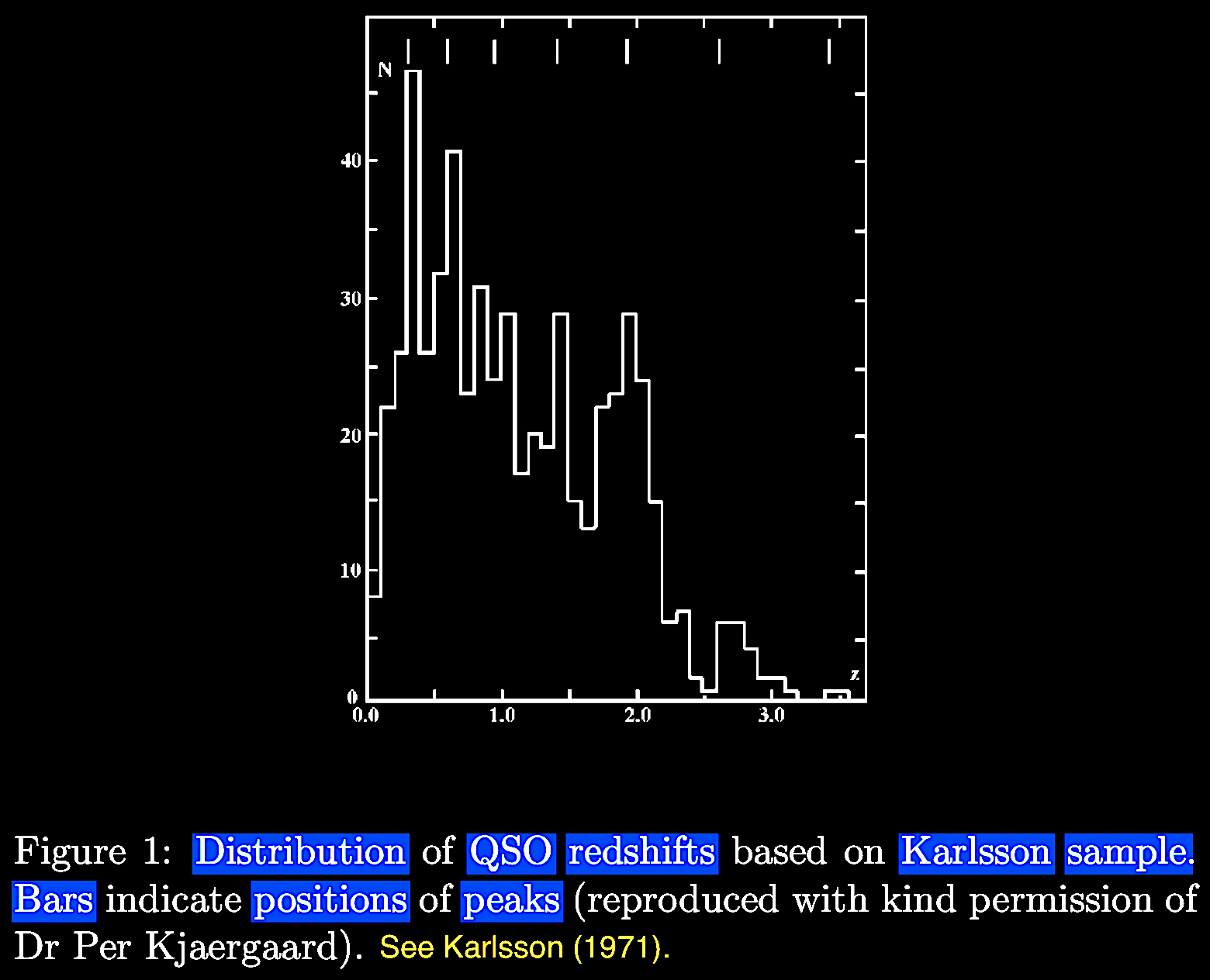

their review they included the famous periodicity paper

published by K. G. Karlsson (1971. Possible

discretization of quasar redshifts. Astron.

Astrophys. 13, 333. https://adsabs.harvard.edu/pdf/1971)

who found peaks empirically predicted in a geometric series:

z = 0.3, 0.6, 0.96, 1.41, 1.96, and predicted at 2.63

and 3.46 (Bajan & Flin, 2007; Figure 1), as well as the

extensive analysis of Hawkins E., Maddox S. J., &

Merrifield M. R. 2002. MNRAS 336 (1), L13.

No periodicities in 2dF Redshift Survey data. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-8711.2002.05940.x.

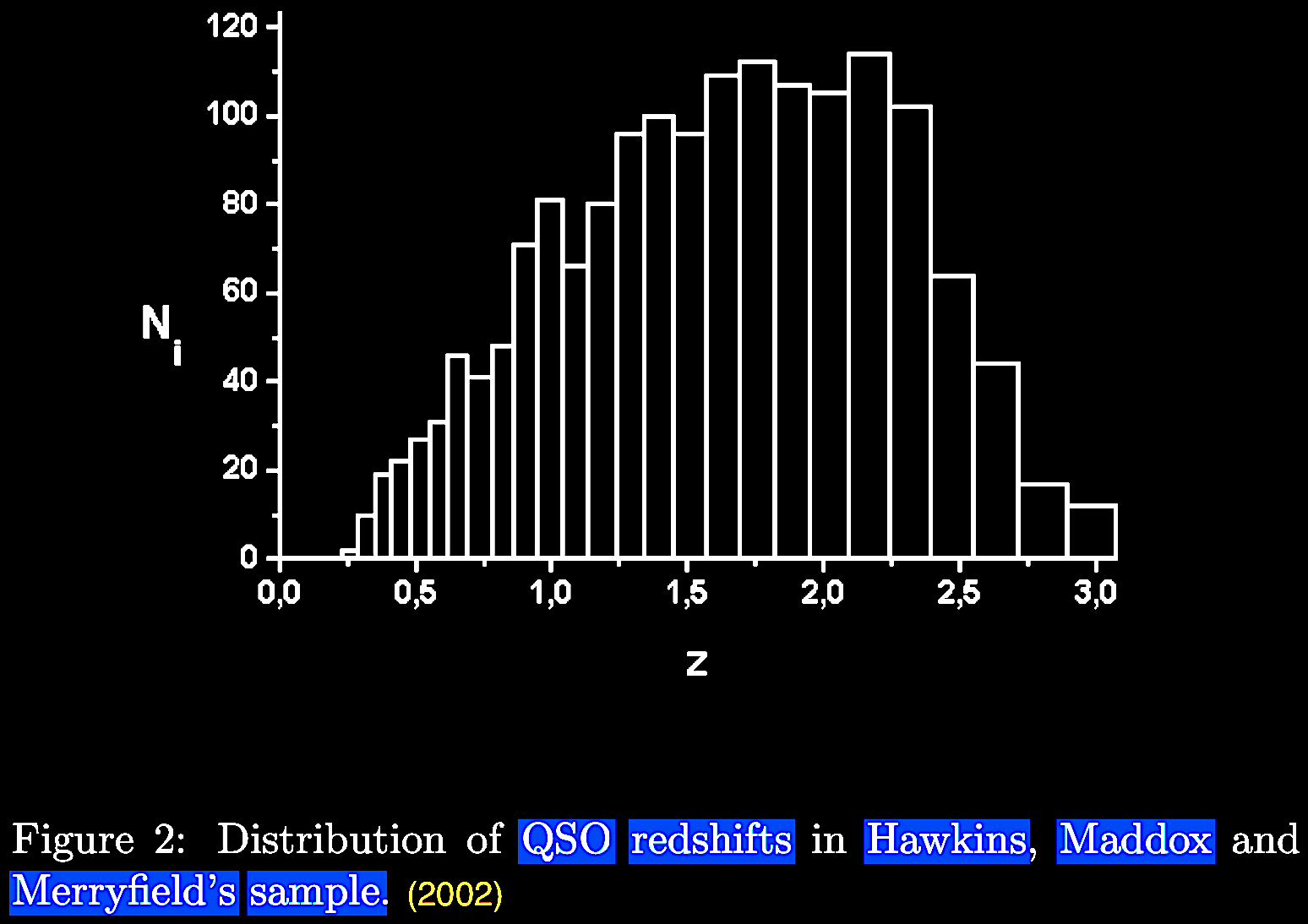

(Bajan & Flin, 2007; Figure 2), from the SDSS data set.

|

|

Many years earlier, following in the empirical astronomy trail-blazed path of Viktor Ambartsumian (1954, 1958, 1961, cf. Arp, 1999. Ambartsumian's greatest insight - the origin of galaxies, in Terzian, Y., Weedman, D., Khachikian, E., [eds.], Active Galactic Nuclei and Related Phenomena, IAU Symposium 194, 473; where Arp recounts Jan Oort's privately whispered confession to him in 1973 that 'You know, Ambartsumian was right about absolutely everything'), Narlikar, J. V. & Das, P. K. 1980. Anomalous redshifts of quasi-stellar objects. ApJ 240, 401. https://articles.adsabs.harvard.edu/full/1980ApJ; and Narlikar, J. V. & Arp, H. 1993. ApJ 405 (1), 51. https://adsabs.harvard.edu/full/1993ApJ argue that QSO redshift periodicities are the result of active galactic nuclei (AGN) ejecting quasars, in accord with the even earlier proposal of a conformally-invariant Machian 'variable mass hypothesis' of Hoyle, F. & Narlikar, J. V. 1964f. A new theory of gravitation. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series A. Mathematical and Physical Sciences 282, 191. http://dx.doi.org/10.1098/rspa.1964.0227; and 1966. A conformal theory of gravitation. Proc. Royal Soc. London 294 (1437), 138. http://dx.doi.org/10.1098/rspa.1966.0199) developed in the elaborations of the CSSC, post-1948; in their C-field formulations).

Theoretical models aside momentarily, the trail blazed by Viktor Ambartsumian and later championed by Halton Arp in galactic cosmology, we in this history tentatively call the Ambartsumian-Vorontsov-Vel'yaminov-Arp (AVVA) cosmogony. Next we turn aside briefly to an excursus on a Machian accounting for anomalous, discrepant or discordant redshifts and redshift periodicity.

References below are cited in full in the Select Bibliography & Resources in the home page).

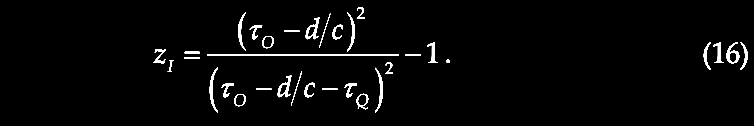

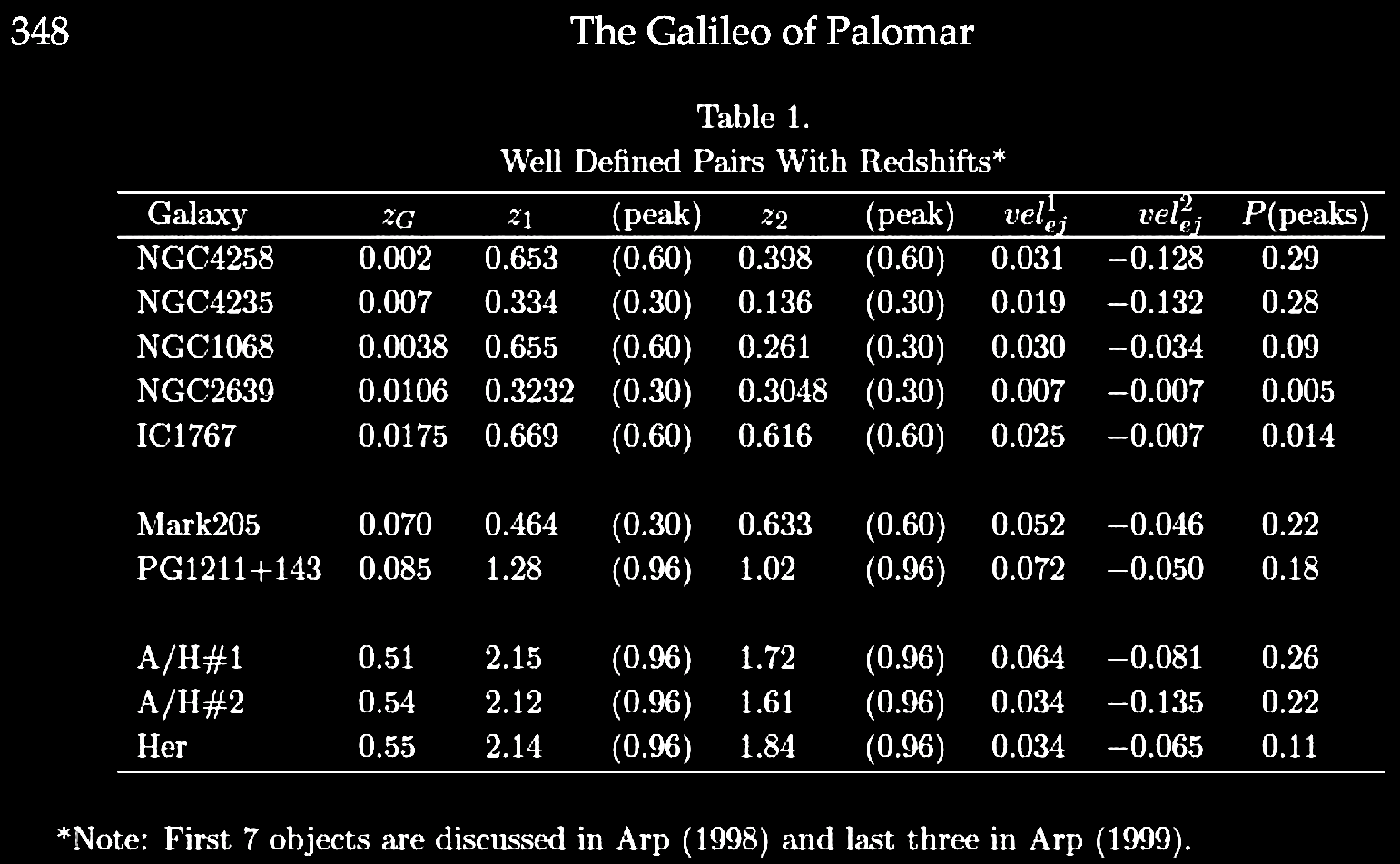

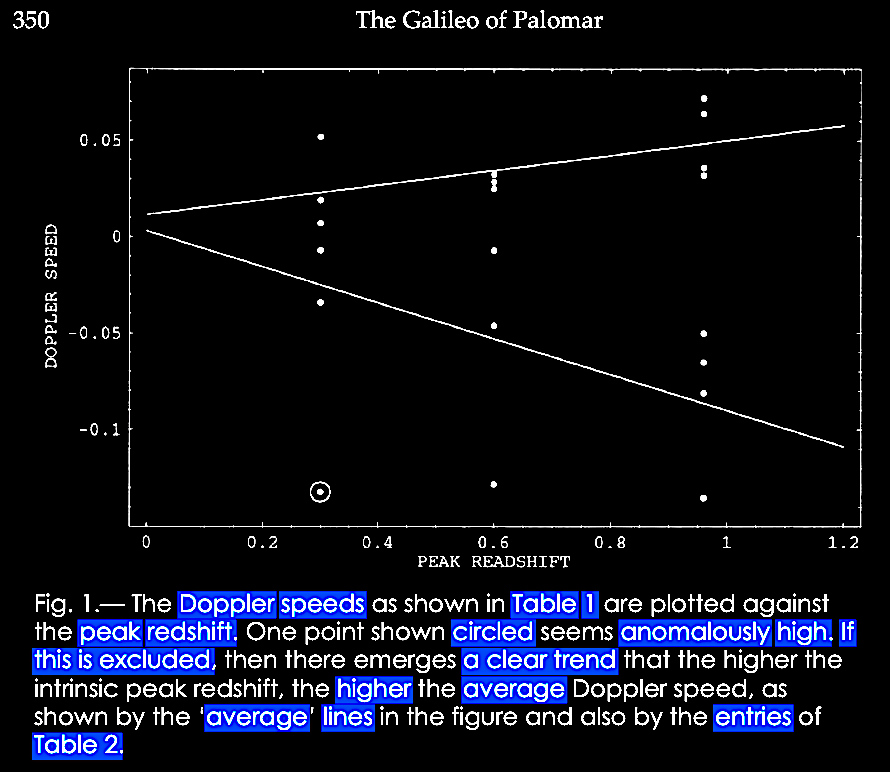

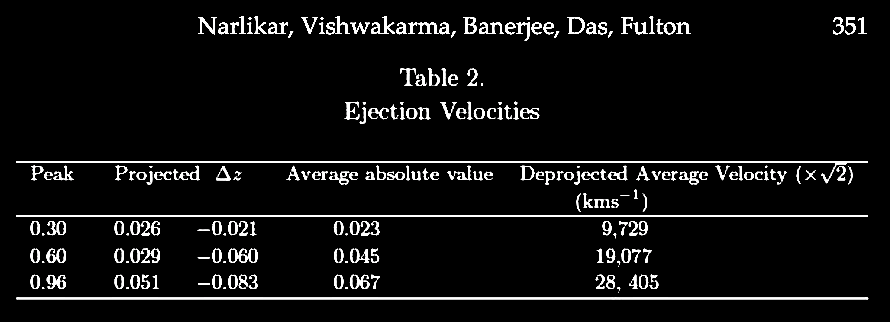

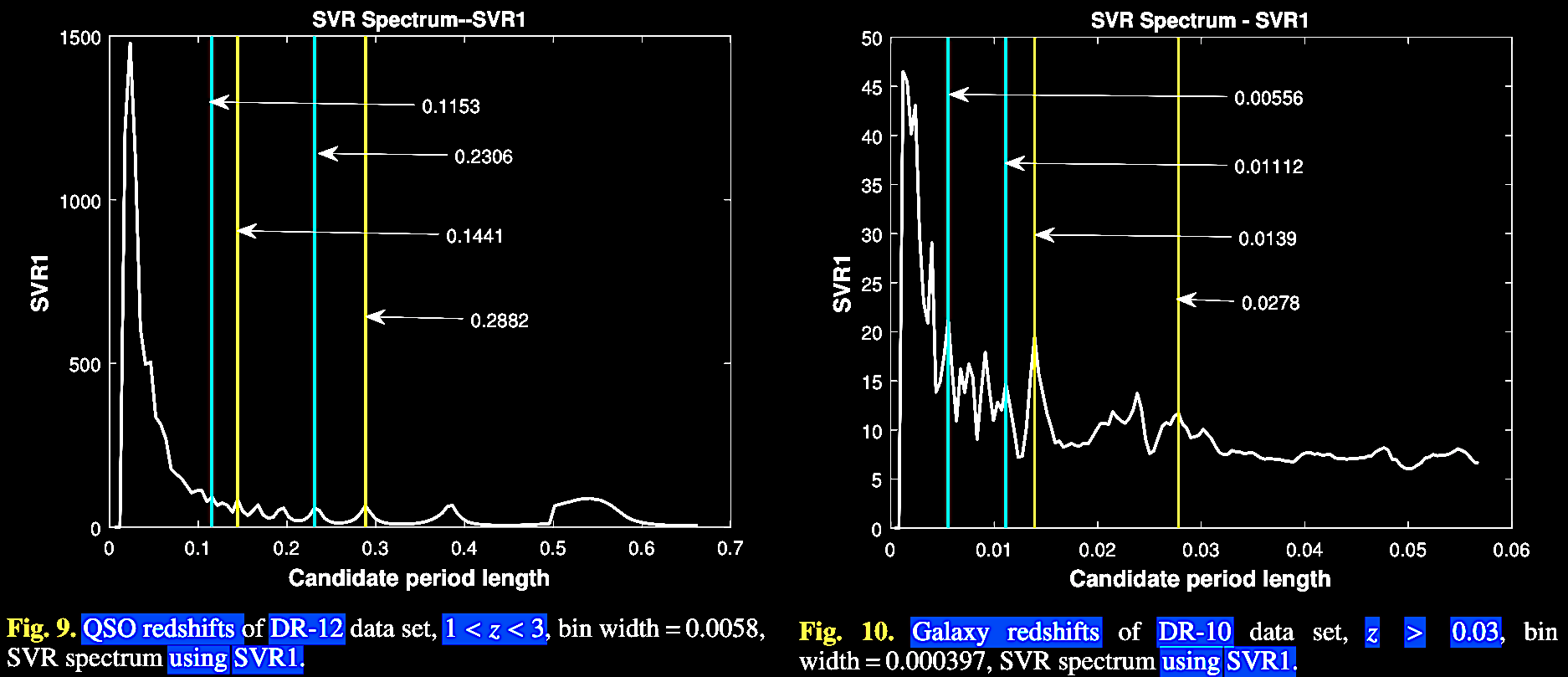

| In 2017, Narlikar and colleagues published

again on the redshift periodicity problem applying the

HN Machian theory within a larger collection of essays

in honor of Halton Arp (1927-2013): Narlikar, J. V.,

Vishwakarma, R. G., Banerjee, S. K., Das, P. K., &

Fulton, C. C. 2017. An empirical approach to periodic

redshifts. In Fulton, C. C. & Kokus, M.

(eds.). The Galileo of Palomar: Essays in Memory

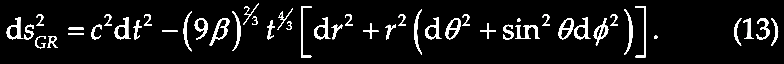

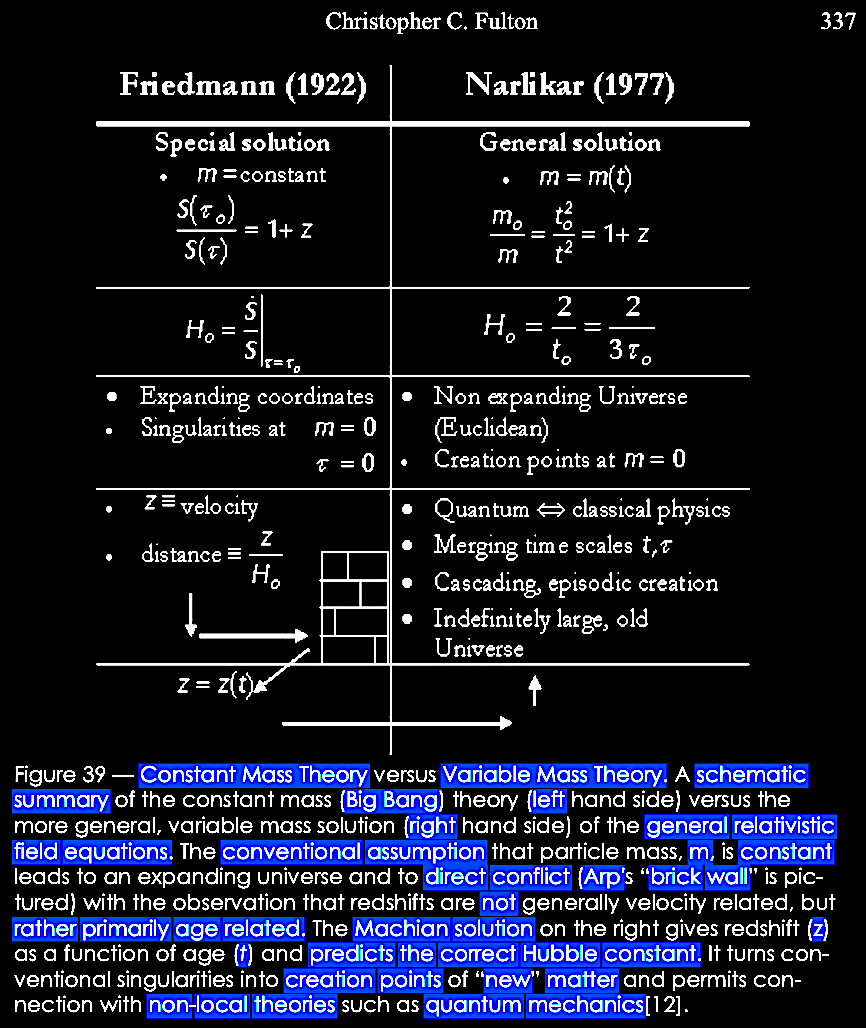

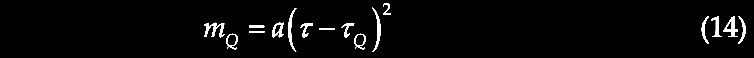

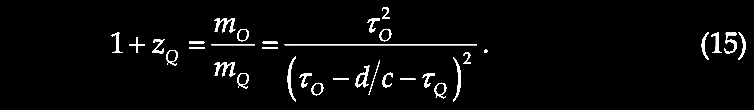

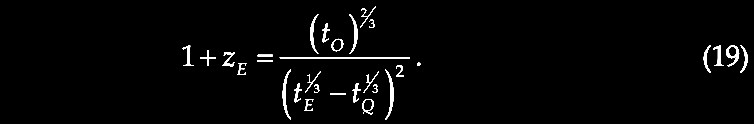

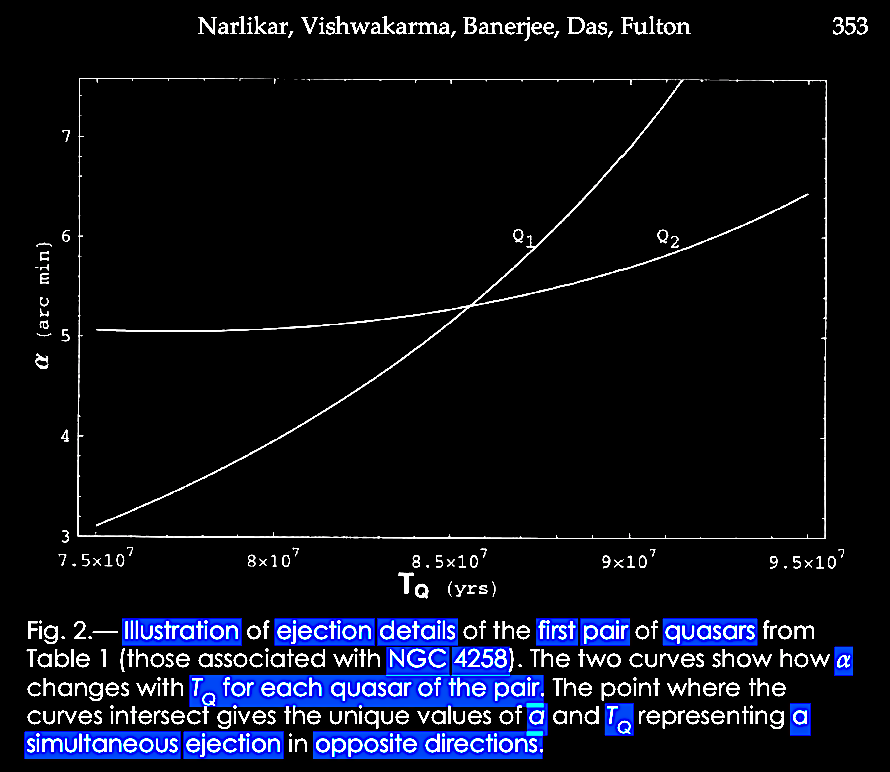

of Halton Arp. Montreal, Canada: Apeiron; pp.